1

I don’t know how Japanese businessman do it, slogging away at their kaisha[1] six days out of seven, week in, week out, with nary a holiday to break up the monotony.

After three months of my own six-day week work routine, I’ve come to the quick conclusion that I’m not cut out to be a salaryman. If it weren’t for the long afternoon breaks, three to four lovely hours out of the crosshairs of Abazuré and my co-workers, I probably would have thrown in the towel a month ago.

I punch out at a minute after twelve and as I’m leaving, Yumi takes a stab at sarcasm, saying it must be nice to always have the afternoons off. The bitch, dressed in black from horns to hooves, has to stay in the office until five.

I say, “Yes. Yes, it is. Very much so,” and hurry out the door. I drop by my apartment and change into something more comfortable, then leave for the station where I’m supposed to meet Tatami at half past. On the way, I pop in the neighborhood kombini (convenience store), the 7-Eleven next to the fire station, to pick up some snacks and drinks.

At the drinks cooler, a lovely girl stands next to me. She giggles when she sees the contents of my basket—full of snacks and beer. I have a look at the content of hers—a bentō, a bottle of oolong tea, and pantyhose, and have a laugh myself. Oh, how I’d love to blow Tatami off and take this girl back to my place for a proper Show-and-Tell, but, after weeks of being treated like a mangy dog by the women at work, I haven’t got the confidence to do so. I smile, nod, mouth konnichiwa, and scurry off towards the register, itchy tail between my legs.

A middle-aged student of mine who works part-time at one of these Sebun-Irebuns while her kids are away at school told me something that was surprising. The clerk punches in a variety of information about each customer before ringing up the sale—male or female, approximate age, and so on. This along with information about what has been bought and other data is immediately beamed to Sebun-Irebun’s headquarters where it is collected and analyzed by computers seeking to further increase the convenience store’s sales and, presumably, put the Lawson convenience store a block away out of business. The information by these mini-surveys is used to maximize the efficiency of the convenience store’s layout and display. Salty snacks are placed near the beer cooler so that the shopper unwittingly picks up a pack of potato chips when all he came in for was a can of beer. To get to the checkout counter, shoppers have to pass by the bentōwhere they will, more often than not, drop a small packet of prepared food into their basket. Gum and mints and other unnecessary, but inexpensive items compulsively bought are within easy reach before the register, and the cigarette rack tempt you at eye height as you pay for your stuff. No stones are left unturned in order to part the customer from his hard-earned yen. So, in the name of recalcitrant consumerism, I’ve considered trying to gum up the system by making irrelevant purchases, such as buying feminine hygiene products with beef jerky, condoms with Ribon, a manga for young girls, and a toothbrush with wasabi paste.

Once my data has been beamed to 7-Eleven’s GHQ, I head to the subway station where Tatami is waiting for me, overdressed as always. Today, she is wearing an odd-looking dirndl reminiscent of a Tyrolean fraulein. It wouldn’t surprise me if she were to jump up, slap the heels of her shoes, and yodel.

2

After Reina and I split up for the nth and final time, I was at a loss what to do with myself. Not that I was down in the dumps about the break up, but I wasn’t exactly dancing a jig on the grave of our relationship either.

I was missing out on more than just the kinky sex. For one, I never did get to see any fireflies, or hotaru as they are called here. It was like trying to pry state secrets from hardened spies to obtain any relevant information about the damned bugs. Oh, I did learn that Auld Lang Syne was known as Hotaru no Hikari, or The Glimmer of Fireflies in Japanese, that Ken Takakura who had starred in my primer on Japan, Black Rain, had also starred in the Kamikaze classic film, Hotaru. I also learned that there was an anti-war animated film by Hayao Miyazaki called Hotaru no Haka (Grave of the Fireflies). But no one could offer me any advice on where to see them, other than to schlepp up some river after sunset. In a city with hundreds of rivers, streams, creeks and brooks, that was no help at all.

No longer spending time with Reina after work or at weekends also brought home once again how utterly alone I was. It wasn’t Reina I missed, or the crazed animal sex we had, for that matter. What I missed hadn’t changed: having someone I cared for in my life, someone to fill the gaping hole Mié had tore open in me.

With nowhere in particular to go and no one in particular to see, I started wandering around town alone, exploring on foot whenever the weather permitted. Since we were apparently having one of the dreariest rainy seasons on record, my excursions were few and far between, but when I did get out, the things I discovered—the architecture, the gardens, the hidden parks, the historical buildings—provided the distraction I was starved for, and encouraged further strolls.

Many of the more interesting sites in Fukuoka are fortunately within a short walk from my apartment: the castle ruins with its maze of stone ramparts, and Ōhori Park, which has a small, but beautiful Japanese garden. A Noh theatre and art museum are also located in the area, as is Gokoku Jinja and a martial arts center called Budōkan.[2]

Gokoku Jinja, like Tōkyō’s infamous Yasukuni, is a shrine dedicated to those who died defending Japan. Had I known this little fact before visiting the shrine, I may have been moved in an altogether different way. Instead, I was inspired with a deep sense of awe, the very awe which was sorely absent when my father would drag his unwilling brood at an ungodly hour every Sunday morning and stuff it into the first two pews of our dimly lit, dusty old house of worship where we’d reluctantly take part in that hebdomadal morose pageant, Mass.

No, if the divine and mysterious were to be felt anywhere, it was in shrines such as Gokoku, a serene island of ancient trees, expansive lawns and painstakingly raked gravel. It’s a spiritual oasis in the heart of a frenetically bustling desert of asphalt and condominiums and if you’re not moved to the core when visiting the shrine, then you have no core. With the Catholic church, the nearest I ever got to appreciating the power of the Almighty was at the coffee and donuts bonanza after Mass when dutifully sitting-standing-genuflecting automatons were resurrected with copious amounts of caffeine and sugar.

After a purifying ablution of my hands, I passed between a pair of komainu statues and through a towering wooden torii gate, entering the shrine. At the end of a long the broad path of combed gravel was the shinden, a long, one storey golden structure with a gracefully sloping roof at the edge of a lush and verdant woods. Iron lanterns and straw braiding hung along the eves, and a young woman, her black parasol leaning against the offertory box, bowed her head in prayer. Drawn by both curiosity and a spontaneous reverence, I made my way along the gravel path, ascended the short flight of steps and offered up a pray, myself.

One day my father will ask cynically, “So, now you’re a Shintōist, are ye?”

And I’ll reply, “When was I never one?”

What did I pray for? Happiness, of course.

With the change in my pocket, I bought an o-mikuji, a small folded strip of white paper with my fortune written in Japanese on one side, and, to my surprise, in English on the other.

“Your flower is heather,” the o-mikuji told me. “It means lonely.”

Wonderful.

“You are introverted and like to be alone,” the prognostication continued.

Not really.

“But man cannot live on without others.”

Hah! No man is an island! Plagiarism!

“Let people into your heart, and you will be happy.”

Bingo!

Regarding my hopes and ambitions, I was told to “make efforts, and try to be friendly with a lot of people.”

By gum, try I will!

“Your studies will be all right, if you keep calm.” I took a deep breath, and exhaled slowly, releasing a small fart, redolent of sour milk.

Any more relaxed and I’d be dead.

I was advised to be cheerful, but to not aim too high when looking for a job. It was also suggested that being quiet on dates wasn’t always the wisest thing to do, and, because I was, again, too introverted I must “behave cheerfully.”

Dutifully noted!

Not particularly impressed with this fortune—it was only shokichi, a four out a scale of about six—I tied it onto a narrow branch of a nearby tree and left the shrine.

3

It was around this time in my life when I was wandering aimlessly around Fukuoka in the constant drizzle that Tatami entered my life. Of the seventy or so people I taught each week, Tatami was the only one near my age. This was an entirely and regrettably different situation to what I’d been used to in godforsaken Kitakyūshū where the vast majority of my students were young women. Granted they had been, for the most part, what the Japanese call potato girls—small town girls with small town ambitions—but I would have gladly settled for those potatoes over the old yams and tatter-tots I was currently teaching.

It may have been nothing more than this sustained dearth of nubile women within my proximity, but Tatami charmed my socks off when we first met. So much so that after our first lesson together, I made the mistake of mentioning to that sour puss Yumi what a nice girl I thought Tatami was.

“She’s not just some nice girl,” Yumi chastised me. “She’s an o-jō-san.[3]”

“Oh?”

“She happens to be from one of the richest families in Fukuoka!”

I suppose that was meant to impress me, but I couldn’t give a sour milk fart. So much is made, not only in Japan, of an individual’s status vis-à-vis what their parents or grandparents have achieved as to overlook the fact that the person in question is often a profligate, underachieving arse.

I wasted little time and slipped Tatami a simple note inviting her out for lunch after only her second lesson. It wasn’t that I found the thirty-year-old “girl” particularly attractive—screwing the o-jō-san hadn’t even entered my mind—but, for some reason or another I was drawn towards her. Something about her gentle innocence, the delicacy of her mannerisms and words made me want to know her better. The fact that her father was a professor of architecture at Kyūshū University also had nothing to do with it.

Honest. No really, I mean it. Okay, it did. A little.

Tatami replied by post a few days later, sending me a short letter written on beautiful summer stationery with a gold fish motif. After apologizing effusively for writing, rather than phoning, she confessed that she’d been surprised, but happy with my invitation and was looking forward to having lunch with me the following Tuesday after the lesson.

4

My long walks continued. I’d been coming down with such a severe case of cabin fever that even the heaviest of showers was no longer enough to keep me inside. I’d even traded in my flimsy convenience store umbrella for one from Paul Smith costing ten times as much, just so that I could get out of my apartment and out of my head, as often as possible. Call me Thoreau; Fukuoka, my Walden.

One afternoon, as I was returning from one of my longest walks yet that had my shins and arches aching with a dull, throbbing pain, I dropped in at the Budōkan to see what kind of martial arts were taught there.

At the entrance was a bulletin board with a schedule of classes. On Saturday evenings, big boys in diapers pushed themselves around a clay circle. Sumō wasn’t really my cup of tea, which is just as well; of all my blessings, girth is not one of them. Three evenings a week, the kendō members met to whack each other senseless with bamboo sticks. That wasn’t quite what I was looking for either.

I walked over to a small window, stuck my head in, and said excuse me in Japanese, disturbing three elderly men from their naps.

“You really gave my heart a start,” said one of the men as he approached the window.

“Um, sorry about that.”

“Wow! Your Japanese is excellent.”

“Tondemonai,” I replied reflexively. Nonsense! “My Japanese is awful. I’ve still got a lot to learn.”

“Oi, Satō-sensei. This gaijin here says his Japanese is awful, then goes and uses a word like, ‘Tondemonai!’”

Satō rubs the sleep from his eyes says, “Heh?”

“How can I help you?”

“I’m, um, looking for a kick boxing class. You got any?”

“Kick boxing? No, I’m sorry we don’t. We do have karate, though. Tuesday and Thursday evenings. And there’s Aikido on Wednesday and Friday evenings.”

“Nothing in the afternoons?”

“No, only in the evenings.”

“Well, what about jūdō?”

The man’s eyes lit up. I was in luck, there was a class in session now, he said pointing to a separate building across the driveway.

“That building?” I said. I had my doubts.

“Yes, yes. Just go right over there. Tell them you’re an observer.”

I wasn’t sure the old man had heard me correctly, but I went to the adjacent building all the same, and removed my shoes at the entrance. As I stepped into the hall, two women in their fifties wearing what looked like long, black pleated skirts and heavy white cotton tops minced past me, their white tabi’ed feet[4] sliding quietly across the black hardwood floor. A similarly dressed raisin of a man, upon seeing me bowed gracefully, then glided off to the right from which the silence was broken with the occasional “shui-pap!”

“Anō,” I called out nervously. “I was told to come here. I’m, um, interested in learning jūdō.”

“Jūdō?” the elderly man asked.

“Yes, jūdō.”

“This isn’t jūdō,” he said, eyeing me warily. “It’s kyūdō.”

“Kyūdō?” What the hell is kyūdō?

He gestured nobly in the direction the “shui-pap!” sound had emanated from and encouraged me to follow him to a platform of sorts overlooking a lawn at the end of which was a wall with black and white targets.

“Kyūdō,” the man told me again. The Way of the Bow.

He instructed me to watch an old woman who had just entered the platform carrying a bow as long as she was short. She bowed before a small Shintō household altar, called a kamidana, then minced with prescribed steps to her place on the platform. Her posture was unnaturally rigid: her arse jutted out, spine curved back. Her head was held high. With her arms bent slightly at the elbows she raised the bow upward, bringing her arms nearly parallel to the floor. She then adjusted the arrow, stabilizing the shaft with her left hand and fitting the nock onto the string with her right hand. She turned her head ever so slowly, and, fixing her gaze on the target some thirty yards away, raised her arms, bringing the bow to a point above her head.

Inhaling slowly and deeply, she extended her arms elegantly, pulling the bowstring back with her right hand, and pushing the bow forward with her left, such that the shaft of the arrow now rested against her right cheek. The old woman paused momentarily before releasing the arrow. The string snapped against the bow with the “shui-pap” I had heard before, and the arrow was sent flying majestically right on target. It fell ten yards short, landing in the grass with a miserably anticlimactic “puh, sut!”

A small, nervous laugh snuck out before I could stop it. The old man at my side gave me a nasty look then went over to the woman who had just delivered the lawn a fatal shot and praised her effusively. She remained gravely serious, bowed deeply, then bellowed: “Hai, ganbarimasu!” I shall endeavor to do my best! All the other geriatrics there suddenly came to life and also shouted: “Hai, ganbarimasu!”

When the old woman had minced away, another man came out onto the platform and went through the very same stringent ritual. He ended up shooting his arrow into the bull’s-eye of the target . . . two lanes away. He, too, was lavished with compliments by the old man, whom I’d only just realized was the sensei, the “Lobin Hood” to these somber “Melly Men and Women”, if you will.

A third man walked onto the platform with the very same gingerly steps and bowed as the others had in front of the kamidana. Standing with a similarly unnatural posture, he went through the movements before releasing his arrow. To my surprise, the arrow actually hit the target. No bull’s-eye, mind you, but close enough for a cigar. And just as I was thinking, “Now here’s someone who finally shows a bit of promise,” the sensei marched over and ripped the man a new arsehole. His form was apparently all-wrong. The poor bastard looked thoroughly dejected as he slinked off the platform.

5

“You know, it’s my patron saint’s feast day today,” I said to Tatami as our bus approached.

“Your patron saint?”

“Yes, Saint Peter. The twenty-ninth is his feast day.”

“Feast day?”

“Yeah, it’s a kind of memorial day.”

“For whom?”

“For Saint Peter.”

“Saint Peter? Who is that?”

“My patron saint.”

“Your patron saint?”

“Ugh, never mind, it’s not that important.”

“Are you religious, Peadar?”

“Ha! Does the Pope poop in the woods?”

“I’m sorry? Poop?”

“No, no I’m not. Not at all,” I said. If my strict Catholic upbringing succeeded in anything it was this: it had turned me completely off the Faith. To this day, I remain a gleefully recalcitrant, devout apostate. “I just thought you’d find it interesting is all.”

“I don’t understand.”

“And neither do my parents.”

We had lunch in a small Malaysian restaurant in Nishijin, and, when we were finished dining on beef satay with a deliciously sweet peanut sauce, spicy chicken tomato curry and nasi goreng, Tatami asked me why I had written her the letter.

Letter, what letter, I thought. All I did was slip the girl a simple note inviting her out for lunch. Why had I written? Because I didn’t want to have lunch alone is why.

Before I could answer that I hadn’t really put that much thought into it, she began to dribble on melodramatically about how happy the letter had made her. She’d been going through a difficult, sad period in her life, she explained but gave no details. Then, once more she asked me why I had written her.

I still didn’t have much of an answer to give her and was beginning to feel guilty for unwittingly leading her to believe differently. I had met a nice girl I was interested in becoming friends with. I wrote her a simple note telling her so. What was there to explain?

“I don’t know, Tatami. I guess I just felt . . .”

“But of all people, you wrote me. Have you written anyone else? No? See! So, why did you write me?”

“I, uh . . . I, just . . .” All I could do was look at my reflection in the tabletop and smile defeatedly.

6

I went back to the Budōkan the following day to begin kyūdō lessons in earnest, not so much out of a burning passion for the martial art itself as a consequence of an adherence to the Taoist doctrine of wu wei—the art of letting be, or going with the flow: I had got this far, and was curious where it might take me. It was a mistake, although I didn’t know it at the time.

With Tatami, it wasn’t much different. She phoned one night and launch into a series of apologies for the rudeness of calling.

“This is why people have phones, Tatami.” I’d only had mine installed a few weeks earlier after buying the line from an America who needed cash—quick. He didn’t say so, but I got the impression that he’d knocked someone up and had to pay for the abortion.

“Yes, but . . .”

“Tatami, it’s quite all right. I’m just . . .”

“But, surely, you must be busy . . .”

“I’m not busy. And don’t call me ‘Shirley’.”

“Pardon me?”

“Tatami, I am not, I repeat, not busy.”

“You’re not studying?”

“Studying? No, no, no. I’m just watching TV . . .”

“Oh, I’m so sorry to disturb you.”

“Tatami, you’re not disturbing anything. It’s just the news and I can barely understand it at that.”

“I can call back later if you like.”

“No, no, no! What is it?”

“I’m sorry,” she said with a nervous laugh, then started drilling with questions me about work, the situation with my co-workers, and so on. Then, just as I expected, she started in with the letter business again: “Peadar?”

“Yeah?”

“Why did you write me?”

I banged the receiver against my head. “Why are you making such a big deal out of nothing, Tatami? I liked you, so I wrote you a letter. End of story.”

“Yes, but why do you like me? I think I am just an ordinary, a very, very, typical Japanese woman. Why do you like me?”

God help me.

The woman was impervious. No matter what I said, no matter how I tried to explain that I had found her amusing was interested in being friends, it always came back to:

“But, I am afraid I don’t have a confidence to be your ‘special’ friend.”

There was a pause, a silence which conveyed more than all the words she’d uttered in Japanese and English until then. I sighed a long “ahhh” like a tire gradually losing its air when it finally dawned me what she was trying to get at in that irritatingly circumlocutory manner of hers.

Before I could step on the breaks and bring this careening jalopy of ours to a screeching halt and tell her in no uncertain terms that I was not interested in her in that way at all, she began to repeat what she had said at the Malaysian restaurant about how happy my letter had made her.

“I have another ‘special friend’, he is so gentle and kindly. I told you about him. I told you he is a gay . . . When he first told me, I felt so dirty and I cried for many, many months. I didn’t want to see him again . . . But gradually, little by little, I came to accept him. I accepted that he is a gay . . .”

“Gay.”

“He is a gay.”

“He’s gay. I’m gay. We’re all gay.”

“Oh no! You’re a gay, too?”

“No! I’m just trying to correct your English, Tatami. It’s not ‘a gay’, it’s just ‘gay’.”

“Oh, I see, thank you. I accepted that he is a just gay.”

Somebody stop me before I go and strangle the girl.

“And we have become good friends,” she continued. “You know, after he told me, I was very sad. I thought I could never have a chance to marry. I gave up and decided to open my own, very small, flower arrangement class and not marry . . . But then you wrote me and it made me so happy . . .”

Dear Lord in Heaven! No! No! No!

“I would like to be a ‘special friend’ for you but I don’t have a confidence.”

“I don’t have confidence,” I corrected again out of habit.

“Oh, you, too?”

“No, no, no. ‘Have confidence’. ‘Confidence’ is an uncountable noun so you don’t need the indefinite article ‘a’.”

“Pardon me?”

“Just ‘confidence’.”

“Oh, I see,” she said. “I would like to be a ‘special friend’ for you but I don’t have a just confidence.”

Argh!

Tatami went on and the more she spoke, the more I felt I was being drawn into playing the part of a frustrated suitor. No matter how absurdly remote from the truth that was, I couldn’t get a word in edgewise to unravel the myth she had so painstakingly spun like a cocoon around herself.

The truth was far more prosaic than her elaborate, but cozy homespun fiction. All I’d wanted was to meet people and make friends who could distract me from all the punishing gauntlet of anniversaries of my time with Mié. I didn’t want to keep spending my days alone, brooding over past mistakes and contemplating all the “what if’s” that made me clutch like a drowning man at the impossible wish of going back in time and undoing all my mistakes—saying yes when I had said no, turning left where I had turned right, breathing in when I had breathed out.

Yes, I wanted a girlfriend, wanted one so desperately I could barely see straight, but I never even toyed with the idea of Tatami becoming the one. Why did I write her? Because she was . . . available. Close to my age, somewhat fluent in a just English and, being a good girl from a good family, she didn’t have to fiddle with bourgeoisie things like a job, so she had oodles of time on her hands. Love or sexual attraction had nothing to do with it, yet here I was being told like a naughty lap dog to behave.

“Tatami, you . . . don’t . . . quite . . . understand,” I interrupted in vain. No, she was determined to make sure that what might have been should never be allowed to happen. She explained further how her father would never understand; he would rip the plant out by the roots rather than wait for any buds of a romance to appear on its branches.

“So,” Tatami concluded, “I’m afraid I cannot give you my phone number. You mustn’t call me because my parents would never understand.”

I was forced into a corner, and the only way out was to accept that the two of us could never be anything more than casual friends. For Tatami’s benefit, I ended up pretending to search within myself the strength to acquiesce, and then feigned disappointment. It was the least I could do.

When she finally hung up, two goddamn hours later, I realized that I hadn’t managed to communicate a genuine and honest thought to her. So, I tried again. I sat down and wrote in the simplest, unambiguous way that my original desire to ‘just be friends’ had meant precisely that and nothing more, that she had been mistaken in thinking I had been interested in her in any other way.

A day later, she replied in kind with an apologetic letter promising me that she would “try her best” to be a good friend to me. I didn’t know if I should be happy or not.

7

I didn’t want the other members at the Budōkan to think of me as a mikka bōzu, that is a-three-day monk, which is what they called quitters here, but of all the martial arts I could have ended up doing, kyūdō must have been zee vurst. Being pushed around by big boys in diapers in the sumō ring would have been a vastly more entertaining.

My training progressed with unnervingly small baby steps with each visit to the dōjō. During the first several lessons, I was not allowed to even touch a bow. Instead, I was made to practice how to step properly into and then walk within the staging area. Oh yes, and how to bow reverently before the goddamn kamidana.

After weeks of mincing effeminately, I was allowed to move on to the next stage which involved going through the elaborate ritual of holding the bow, threading the nock with the bow string, aiming and releasing the arrow. Problem was, I had neither bow nor arrow and was asked, rather, to rely on my fertile imagination. Several days of this humiliation were followed by at last the opportunity to hold a bow and practice releasing imaginary arrows at an imaginary target. After the hour-long practice, I would have tea with my imaginary friends.

In the meantime, Tatami still had reservations about dating me, so we ended up using our mutual studies as a ruse to meet regularly. Not at my place, of course—that was unthinkable—but, at coffee shops or in the Mister Donut near the park. Though I couldn’t have been happier with this arrangement—I needed more friends like her who’d patiently listen to me as I butchered the Japanese language—Tatami continued to fret about her inability to be there the way she had convinced herself I wanted her to be and worried that she was wasting my time.

I couldn’t understand what Tatami was carrying on about half the time. And, to be honest, I didn’t really care. I just figured she would eventually come to her senses and accept our relationship free of any troubling nuances. In the meantime, I fell into an odd habit of encouraging and assuring Tatami that I appreciated her friendship, however constrained, exactly as it was. And each time when the poor girl faltered, I would raise her up, by reminding her, “I need your friendship, your companionship, and your help.” But you know, the funny thing is the more I told her this, the more I started believing it myself.

8

One rainy afternoon Tatami and I went to a wonderful little coffee shop near Ōhori Park. Like many of the better restaurants and bars in the city, you could easy miss the coffee shop if you weren’t led by the hand and pushed through its door.

I fell in love with the place as soon as I entered. There was a long counter running the length of the narrow shop that was covered with black straw mats. Three of the interior walls were covered with dark mud specked with straw, the fourth wall behind the counter was covered with Japanese roof tiles with water trickling down through them.

“I love this place,” I enthused as I opened a menu hand-written on washi paper. “Not crazy about the prices, though. Ouch!”

“Do you have coffee shops like this in America?”

“Ha-ha . . . No.”

“No?”

“No. For one, I don’t think you’d find many Americans who’re as fussy about details as you Japanese are, or customers capable of appreciating the attention paid such details. And, two, there’d be a riot when they saw how much the coffee cost.”

“Oh, is this expensive?”

“My dear Tatami, eight bucks a cup ain’t what you’d call cheap.”

Speaking of “three-day monks”, Tatami had worked a sum total of two days her entire life. Upon graduating from college, she entered a major Japanese company with a branch office in town, but was so disgusted with her male co-workers that she quit. There was no way she could possibly relate to a working stiff like me about money.

I ordered a caffé con frecce, a kind of Vienna coffee made with brandy. It was excellent, and, well, at twelve bucks a pop, it damn well better have been.

Though Tatami and I usually spent our afternoons together chatting, we actually did get down to studying from time to time. On this particular day, Tatami had brought a pile of assignments from the translation school she was attending every week, and I had taken my kanji drill book and several grammar worksheets along that I needed to prepare before my next lesson at the YWCA.

As I scribbled down kanji in the drill book, Tatami worked on her homework, occasionally interrupting me to ask what this word or that word meant or whether her choice of words was correct, and so on.

When she wanted to know what “hard-of-hearing” meant, I asked her whether her grandparents were still alive. They weren’t, she answered, and reached for her Genius English-Japanese dictionary. It was the size of a honey-roasted ham. I, too, had brought my set of Takahashi Pocket dictionaries. A bit of a misnomer as so many things are in Japan, the set was so large that the only pockets they could have possibly fit in were those of the pants of a rodeo clown.

Did she have any elderly aunts and uncles? Yes, but she’d go on to tell me that they all could hear fine. Then, I asked if she knew what ‘deaf’ meant. She did. “Right, ‘hard-of-hearing’ is when you’re not quite deaf, but you’re getting there.” She said she thought she understood, but continued looking up the entry in that honey-roasted ham all the same.

“Atta. atta! Hard-of-hearing is mimi ga tōi in Japanese.”

“I’ve heard that before,” I said. “‘With distant ears’.”

“Can you also say ‘hard-of-seeing’?”

“Nah, I don’t think you’ll find any other ‘hard-of-somethings’ in your dictionary.”

“Hmm,” she said, looking at the entries in her dictionary. “A hard nut to crack; hard-of-hearing; hard-on . . . Oh dear!”

When I noticed how red Tatami’s face had become, I almost lost it, but then it dawned on me that that may have been the closest the o-jō-san had ever gotten to an actual erection. Had I laughed, she would have scurried out of the coffee shop, scandalized.

The dictionary, I discovered that afternoon, was a minefield of sorts that needed to be trod with care. If you ran in carelessly after a “hung jury” as Tatami also did that afternoon, you’d step on the explosively lascivious phrase “hung like a horse”. “Cunning” is never far from “cunnilingus”, a “fellow” always chases after “fellatio”, and “fuchsia” is colored by the word “fuck”.

When it was getting time for me to return to work, I settled the bill, which left me about fifty dollars poorer.

“Sheesh! Remind me the next time to only have one cup of coffee.”

“I’m awfully sorry about that.”

“Ah, don’t be. It’s a great place, Tatami. I’m really glad we came. Thanks.”

“Here,” she said, holding some bills out. “Please. I insist.”

“It’s okay, Tatami. My treat.”

“But, I insist.”

“So do I.”

“But I feel bad.”

“Tell you what, Tatami, you get the bill the next time we meet.”

“Okay. But promise you’ll let me pay.”

“I promise.”

“No. Promise like this,” she said, holding out her pinky and hooking it around mine. “Yakusoku?”

“Hai, yakusoku shimasu,” I promised.

9

When Tatami called a few days later, I suggested having dinner the following Wednesday.

“Wednesday?”

“Yes, Wednesday evening,” I said looking at the sumō calendar a student had given me. It featured the Hawaiian yokozuna[5] Akebono striking a menacing pose. “Wednesday. Wednesday, the seventh.”

“The seventh?”

“Yes, the seventh of July.”

“But, I don’t think it’s . . .”

“If it’s the time you’re worried about, I’ll finish earlier than usual next Wednesday, so it’s not . . .”

“No, no, it’s not that. It’s just that . . . I think that . . . maybe it’s not such a good idea to meet in the evening. Especially, on the seventh.”

What was the deal with the seventh, I wondered. I knew I’d have to ask half a dozen people before I could get something resembling a straight answer, so I didn’t press the issue with Tatami.

“But . . . I can meet you in the afternoon,” she added brightly.

“The afternoon, huh? Yeah, that’s fine, but I won’t have as much time as I usually do. See, the schedule’s a bit different next week.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. That was very inconsiderate of me . . . I didn’t know you were busy.”

“Tatami!! Give it a rest, will you! I am not busy, but I’ll only have about two hours off.”

“I’ll tell you what! I’ll prepare bentō for us.”

So, we meet at half past noon at the station, and, like I’ve said, she’s wearing an odd Alpine dirndl dress of sorts.

“Guten Tag, Fräulein,” I say.

“Pardon?”

“Wie geht’s?”

“Sorry?”

“Roll out the barrels, we’ll have a barrel of fun?”

“Peadar, are you feeling unwell?”

“Yeah. Sorry, I’m just teasing you.”

“Moh! You’re always teasing poor Tatami.”

“I can’t help it. You bring out the worst in me.”

Tatami leads me out of the station, saying there’s something she wants me to see.

“We’ve got lucky with the weather,” I say once we are outside. Not the sunniest of days, but at least it isn’t raining.

“If we’re lucky we’ll be able to see the stars tonight.”

“Stars?”

“Orihime and Hikoboshi.”

“Ah, right, those stars.” I have no idea what she’s talking about.

Tatami opens her parasol and we begin walking along Meiji Boulevard toward Ōtemon where the main gate of the former castle stands across the moat at the end of a tree-lined causeway. The moat itself is teeming with lotus plants, huge, floppy leaves the size of sombreros sticking a good five feet above the surface of the moss-covered water. Here and there, white lotus flowers as large as cabbages tower on long narrow stalks above the leaves. Dragonflies rest on the flowers.

We sit down on a bench near the causeway overlooking a small pond bordered on the far side by the Ōtemon Gate, one of the four remaining structures of the ancient castle. Half of the pond is covered with low-lying lily pads and a different kind of lotus flower, deep yellow in color and floating on the water. A family of ducks waddles across a grassy bank towards us when Tatami removes the bentō from her basket. She has wrapped the urushi lunch boxes in a furoshikicloth which has a simple design of purple morning glories.

“What did you bring?” she asks me.

“Oh, just some drinks and snacks,” I reply, taking the contents of my 7-Eleven bag and placing them onto the furoshiki. “I didn’t know what you liked, so I just bought a little bit of everything.”

Between us on the furoshiki are cans of Asahi beer and bottles of Pocari Sweat, oolong tea and Calpis. There’s a Woody candy bar, sugarless Titles breath mints, Baked Chunk cheesy puffs, Men’s Pocky and . . .[6]

“Pecker!” Tatami says.

“You like Pecker?”

“I love Pecker!”

“I bet you do.”

She makes a go at it, but I grab the Pecker first.

“Tsk, tsk, Tatami. This is my Pecker, and you can’t have it.”

“But, I want your Pecker! I want your Pecker! I want your Pecker!”

“Tatami!”

“Give me your Pecker, Peadar!”

So I give it to her. When a woman begs for your Pecker as shamelessly as Tatami does, what’re you gonna to do?

“Are you happy now?”

She nods happily as she opens the box and starts nibbling like a rabbit on the pretzel sticks.

Tatami, exceeding my expectations, has prepared a small, delicate feast packed so neatly into the urushi bentōboxes that it almost a shame to disturb it.

She has prepared onigiri rice balls, some wrapped in nori others sprinkled with black sesame, another with a big pink kishū umeboshi pickled plum in the middle. She has packed the bentō with fried chicken, sausages, edamamé, cubes of tōfu and stewed pumpkin. There are also slices of peach and melon and a small basket of cherries.

“Boy, Tatami, you’ve really gone all out. Thanks!” I say. She lowers her head and smiles.

After an hour of gorging myself, the bentō boxes are empty shells, most of the snacks, too, are gone.

“You want some ‘Baked Chunk’?” I ask Tatami.

“No thank you.”

“I don’t blame you, Tatami. I don’t know what I was thinking when I bought it.”

“You want some mugi cha?” she says, taking a small thermos of barley tea from her bag.

“Already had some,” I answer showing her the crushed cans of Asahi beer, making her laugh.

“You’ll take the Japanese proficiency exam, won’t you?” she asks.

“Yes, but I don’t expect to do well. I’ve still got so much to learn.”

“I think you already study very much now. I respect you for that. Shizuko-san says we should all study English as hard as you study Japanese.”

Shizuko is one of the other students in Tatami’s class.

“Yeah, well, that’s very nice of Shizuko-san to say, but, really, she hasn’t got the slightest idea what my study habits are like . . .” Not that it really matters. Compliments in Japan are like verbal abuse in the US. Everyone says them; few really mean it when they do.

“You had better not forget to apply for the test,” Tatami says seriously.

“Oh, do I have to so soon?”

“By the end of September.”

“The end of September?”

“Yes, September.”

“Why are you telling me this now? In July? There’s oodles of time.”

“Noodles?”

“Not ‘noodles’, Tatami, ‘oodles’. It means ‘plenty’.”

“Yes, but you had better not forget.”

“You know, I have a funny feeling that you’ll be reminding me again,” I say. “So, when’s the test?”

“I am not sure, but I can call Kinokuniya and ask. They will know.”

“No, no, no. That’s quite unnecessary. I just wanted to know if had you got a rough idea when it was held?”

“I think, but . . . now, I cannot be too sure . . . um, I think, maybe, it will be held at the beginning of December.”

“And that’s a Saturday? Or a Sunday?”

“Sunday,” she answered. “The exam is always held on a Sunday.”

“Sunday. Early December. Perfect.”

“Why?”

“Oh, nothing, really.” I say. “I’m just thinking of going to Thailand in December.”

“You’re going to Thailand?”

“No, Tatami, I said I was thinking of going. I haven’t made any plans yet”

“When did you decide this?”

Ugh! I tell her I haven’t decided.

“But you said you were going to . . .”

“No, Tatami. I said, ‘I was thinking of going.’”

“So, when did you start thinking of going?” she says, suppressing a giggle with her right hand.

“You like irritating me, don’t you?”

Nodding, she says, “You deserve it for teasing me all the time.”

“So, I do. So, I do. Last year,” I admit. “Last year, some friends of mine . . .”

“Oh? What friends?”

“It’s not important. They went but I was too busy looking for a job, so I couldn’t join them. If I’d had the money, I would have gone during Golden Week.”

“I didn’t know you went during Golden Week.”

“Huh?”

“I didn’t know you went during Golden Week.”

“I didn’t.”

“But you just said you did.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Yes, you did.”

“Did not.”

“Did to.”

“Tatami! I said ‘If I’d had . . .’”

“I see. I see.”

“Do you really?” I eye her doubtfully. “Anyways, I’ve wanted to go for a long time, so I’m thinking of going this December.”

“When?”

“During the winter break.”

“After the test?”

“I suppose so, yes. During winter vacation.”

“How long?”

“Two weeks.”

“Two weeks?”

“Yes, only two weeks.”

“Only? I think two weeks is quite long.” This is coming, mind you, from a girl who hasn’t worked more than two days her entire life.

“No, Tatami, two weeks is not long, but it’s long enough.”

“Who are you going with?”

“I don’t know. Maybe a . . .”

Before the word “friend” has time to settle, I know what her next question will be. Every time I introduce a new character into our silly little conversations, Tatami subjects me to a string of intrusive questions. For all her gentle sweetness, she would make a hell of an interrogator, breaking the will of even the most determinedly reticent suspect by virtue of her annoying persistence. A girl?

“A girl?” she asks.

“No,” I correct. “A man.”

“What is his name?”

“Does it really matter?”

“Um, no I suppose it doesn’t, but I want to know.”

“Alex. His name’s Alex.”

“Alex?”

“Yes, Alex.”

“And is he an English teacher?”

“No, he isn’t.”

“Oh? What does Alex-san do?”

“He’s a student.”

“Where?”

“Hell if I know.”

“Excuse me?”

“I don’t know.” I don’t know! I want my lawyer!

“And Alex-san lives in Hakata? So, you met him here?”

“No. Tōkyō.”

“You met him in Tōkyō?”

“No, he lives in Tōkyō,” I say.

“And you met him in Tōkyō, right?”

“No, I’ve never been to Tōkyō. I met him here. He used to live . . .”

“And you became a good friend when he lived here.”

I place my finger on her lips to shut her up. “Tatami, let me finish. Alex used to live here in Hakata . . . a while ago. Don’t ask, I don’t know. And now, he sometimes comes to Fukuoka to visit friends. I only met him for the first time at a party about two months ago.”

“What party?”

I raise my fist at her and threaten to pop her in the nose. She apologizes demurely, bowing her head slightly, the palms of her hands resting on her lap.

“I met him at a wedding.”

“Whose wedding?”

“Oh, for the love of God, Tatami! Is it important?”

“Well . . .”

“No! It is not important.”

“Yes, but I want to know his name.”

“Dave! His name is Dave! Happy now?”

“Debu?”

“Not Debu. Dave.” Debu means fatso.

“Ha ha ha. And Debu-san is a good friend.”

“Well, er, not really.” I hardly knew the guy and was surprised to be invited to his wedding. It was only after I accepted the invitation that I began to suspect the reason I’d been invited was so that Mr. Fatso could have one more sucker to collect a gift of cash from.

“So you and Debu-san will go to Thailand together.”

“Alex.”

“Alex, too? Will his wife come?”

“Huh?”

“Alex-san is married. Is his wife . . .”

“No, Alex’s single. Happily so.”

“You just said Alex got married recently.”

“I did not.”

“You did, too.”

“Did not.”

“You said . . .”

“Tatami, I’m sorry to say this, but you’re not a very good listener.”

“And I think your Japanese is not very good.”

Tatami finds this immensely amusing and sits next to me tittering for a full two minutes during which time I untie my right shoe, remove the lace, and begin to strangle her.

“Let’s try this again,” I say and retell the whole non-story without pausing to listen to or answer any of her silly questions, which bubble up like carbon dioxide in a glass of soda with each sentence I complete.

“I see,” she says when I have finished.

As we are cleaning up, collecting the garbage and stuffing it in a plastic bag and wrapping the empty bentō box back up in the furoshiki, it starts to rain. Heavy raindrops fall with a thud onto the damp soil and splatter against the lily pads. Before long, it’s pouring and Tatami and I have to scramble up onto the causeway and duck under the long drooping branches of a willow tree to keep from getting drenched. I open her parasol and we huddle under it, her hand on my arm, her cheek resting lightly against my shoulder.

Were it anyone but her, I’d be thanking my lucky stars, but with Tatami, I just feel uncomfortable. I suggest making a dash for the Ōtemon Gate at the end of the causeway and waiting out the rain there, but Tatami embraces me and says, “I like it her. I wish we could stay here all day.”

Good God, what have I done?

[1] Kaisha means company.

[2] Literally, Martial Arts Hall. This is not the same Budōkan made famous by Cheap Trick’s live album.

[3] An o-jō-san is a girl from a “good” family.

[4] Tabi are Japanese socks that have the big toes separate from the other toes, like mittens for your feet.

[5] A yokozuna is the highest rank in sumō, and generally occupied by a wrestler who has won two consecutive tournaments.

[6] All of these are, or were at one time or another, the real names of products available at convenience stores and supermarkets in Japan.

Click here for Chapter One

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

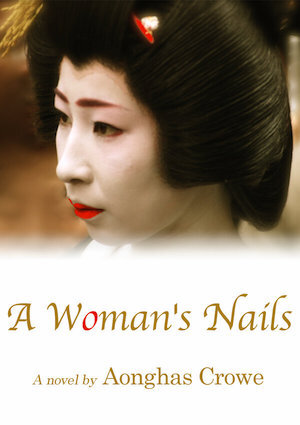

A Woman's Nails is now available on Amazon's Kindle.