There are, or rather I should say were, almost 80 different ways to say kane (money) in Japan. This map comes The National Language Research Institute's Linguistic Atlas of Japan. (Ah, to get my hands on this book!) Some of the ways to say money in Japanese include: zeni, ozeni, zene, zenu, zeno, zini, zinii, zinuu, zyeni, zyene, zyeno, syeni, deni, dene, zen, zin, zenzen, dende, dede, oasi, ginka, etc. The word kane (金) was most likely Edo-ben (Tōkyō dialect) originally, but like many words it gained currency (har-har) when that dialect (also known as Yamanote Kotoda, 山の手言葉 ) was first promoted as "standard Japanese" in the middle Meiji Period. During the war, policies to push "standard Japanese" were suspended, leading to a rethinking of local dialects. The Tōkyō dialect was for a time called a "common language" (共通語).

Money, Money, Money

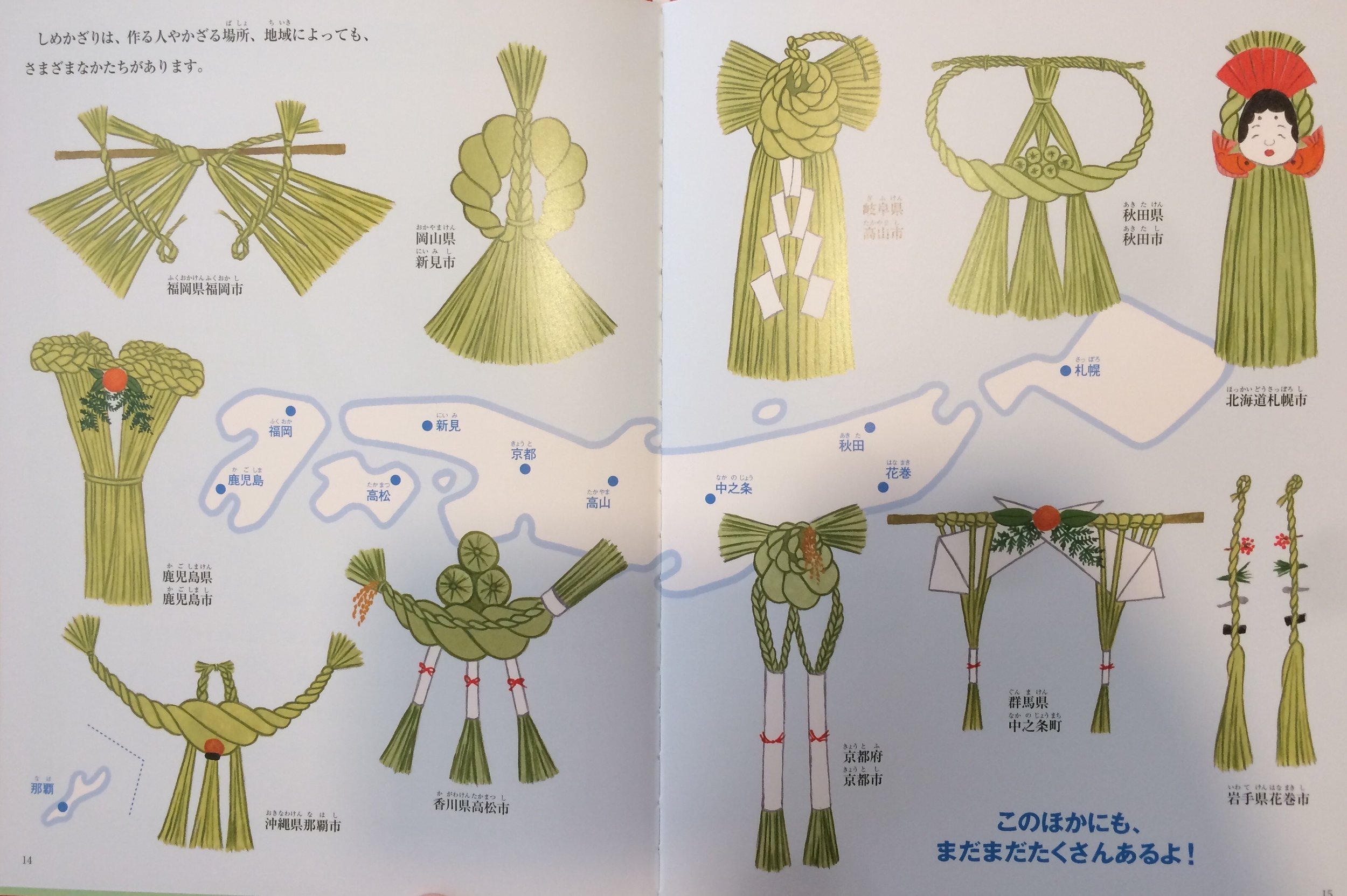

Shimekazari

Shime kazari are the New Year’s decorations you find hanging on front doors and gates during the first three to fifteen days of the New Year. Traditionally made with twisted rice straw, they are festooned with a daidai (bitter orange), fern fronds and gohei or shide (zigzag strips of white paper), the ornaments serve to welcome Toshigami-sama, the deity who brings a bountiful harvest and blessings for the new year.

I used to think that shime kazari were the same everywhere, but to my surprise--I really should be surprised anymore at this point--they vary from region to region, just like language.

Iichiko

The name Iichiko (いいちこ) originates from the Ōita dialect and means “good” (いい, ii). Adding ~chiko (ちこ) is a way to lend emphasis to a word. It is thought that ~chiko may be a contraction of ~cha (ちゃ) and ~kon (こん). Iichiko is used more often to turn something down or refuse something than to evaluate it positively, a duality of meaning similar to kekkō des’ (結構です) and ii des’ (いいです) which can mean both “yes, please” or “no, thanks”. So, brush up your mind-reading skills before coming to Japan.

“Would you like something to drink?”

“Iichiko.”

“Um . . .”

“Iichiko.”

“Eh . . . Was that a yes-iichiko or a no-iichiko?”

“Neither. I want to drink Iichiko.”

“Ah.”

From Wiki:

母「ひろしちゃん、今日はさーみなっき、こん上着を着ちいきない(標準語: ひろしちゃん、今日は寒くなるから、この上着を着ていきなさい)」

Mother: Hiroshi-chan, kyō-wa samī nakki, kon uwagi-o kichiikinai. (Standard Japanese: Hiroshi-chan, kyō-wa samukunaru kara, kono uwagi wo kiteikinasai.)

Meaning: Hiroshi-chan, it’s going to get cold today, so wear this jacket.

ひろし「いいちゃ。今日は、ずっとぬっかろうけん(標準語: いいよ。今日は、ずっと暖いだろうから)」

Hiroshi: Iicha. Kyō-wa zutto nukkarō-ken. (Standard Japanese: Iiyo. Kyō-wa zutto attakai darō kara.)

Meaning: That’s okay. It’ll probably be warm all day.

母「風邪(かじぃ)引いたらつまらんき、着ちいきないちゃ(標準語: 風邪を引いたら困るから、着ていきなさいよ)」

Mother: Kajii hiitara tsumaranki, kichikinaicha. (Standard Japanese: Kaze-o hittara komarukara, kiteikinasai.)

Meaning: Wear it. If you catch a cold, you’ll have a hard time of it.

ひろし「いいちゃ(標準語: いいよ=要らないよ)」

Hiroshi: Iicha. (Standard: iiyo = iranaiyo)

Meaning: I’m fine (= I don’t need it.)

母「着ていきないちこ(標準語: 着ていきなさいってば!)」

Mother: Keteikinaichiko (Standard: kiteikinasaitteba!)

Meaning: I said, wear it!

ひろし「いいちこ(標準語: いいってんだよ!=要らないってば!)」

Hiroshi: Iichiko (Standard: iittendayo = Iranaitteba!)

Meaning: I said I’m fine! (I said I don’t need it!)

Hi-Chew

My wife has a bad habit of sticking a chunk of Hi-Chew (ハイチュウ) taffy into my son's gob whenever he's in a mean and ornery mood. (Often!) It used to drive me crazy until I realized the wrappers featured different phrases in Japanese dialects. Recent wrappers had the following:

Ishikawa

おたべやす (Otabeyasu)

Meaning: 召し上がれ (Meshiagare: Please eat)

Aomori

ごしゃくよ (Goshakuyo)

Meaning: 怒る (Okoru: be/become angry)

Kyōto

まいどおきに (Maido okini)

Meaning: ありがとう (Arigatō: Thank you)

Kanagawa

うめーらー (Umērā)

Meaning: 美味しいでしょ (Oishii desho: Delicious, isn't it.)

Kagawa

もっちゅう? (Mocchū)

Meaning: 持っている? (Motteiru: Do you have . . .?)

Shimane

ぴっぴ (Pippi)

Meaning: うどん (Udon: udon noodles)

I'll post more of these phrases as my son eats the taffy.

Botchan's Na Moshi

Matsuyama City's Dōgo Onsen (hotspring)

Reading J. Cohn's translation of Natsume Sôseki's Botchan I kept coming across the phrase "na moshi" as in the following passage:

"When I asked him what he wanted, he said, 'Well, umm, when you talk so fast it's hard to understand, umm, could you slow down just a little bit if you don't mind--na moshi.' This 'if you don't mind na moshi' sounded awfully wishy-washy to me."

Although Sôseki never explicitly says so in his novel, it is clear from clues throughout the story, including the use of na moshi in dialogue with the locals, that Botchan takes place in the city of Matsuyama on the island of Shikoku.

So what is this na moshi?

Na moshi (〜なもし) is the Matsuyama dialect's equivalent of de gozaimasu-ne (〜でございますね), a phrase that doesn't quite translate into English. Think of it as a formal way to say desu-ne (〜ですね), for which there is no good English equivalent, though, "Isn't it?" comes close.

Some examples:

Matsuyama Dialect: O-samui na moshi (お寒いなもし)

Standard Japanese: O-samui gozaimasu-ne(お寒いございますね)

English: It's cold, isn't it? (Only much more formal.)

Matsuyama Dialect: Sô ja namoshi (そーじゃなもし)

Standard Japanese: Sô degozaimasu-ne (そうでございますね)

English: It is, isn't it.

In the southern part of Ehime, people say nah shi (なーし) or nashi (なし); in the east, they say nomoshi (のもし) or nonshi (のんし).

Although Sôseki made the patois of Matsuyama famous, very few people used na moshi today. 残念なもし。

Genki-Bai!

Finally, an answer to something I should have figured out long ago, but didn't! What is the difference between the copula (sentence endings) ~tai (〜たい) and ~bai (〜ばい).

~tai (〜たい) is equivalent to ~da (〜だ) or ~desu (〜です) in standard Japanese and can be translated into Japanese as is/be.

~bai (〜ばい), on the other hand, has a similar meaning, but is used for emphasis. It is similar to ~dayo (〜だよ) or ~desu (〜ですよ). Like adding a "hurumph" to the end of your sentence.

The pictures were taken during the Dontaku Festival in May of 2005, shortly after our big earthquake in March of that year. The mascots and blimp-like balloons all say "Genki-bai!" (元気ばい!), meaning "We're (as if Fukuoka) are doing great!"

If Tony the Tiger were from Hakata, he would just say "They're grrrreat!" He's say, "They're grrrreat-bai!"