I’m having one of those days where the words just won’t come to me.

I’ve been inundated recently with requests for proofreading and translations, the content of which is so mind-numbingly unreadable it has smothered all inspiration from my heart.

Or perhaps it’s just the weather. Overcast, cold and windy. Oh to be kicking back on a sun-drenched balcony overlooking the sea, a glass of awamori sweating in my hand rather than looking out at a sullen, overcast sky.

As you may already know from reading this blog, I spent the last week of summer vacation with my family in Okinawa. I was hoping to get quite a lot done while I was there, but quickly discovered that even the best-laid plans can be easily sabotaged by the immediate needs of the child in your company. In our case, it was a poorly timed cold that had my son burning with a fever and crying for the first three nights of our vacation.

One of the things I was eager to do while there was tour some awamori shuzô (distilleries) in order to, one, learn exactly how the Okinawan fire water is made, and, two, discover some new favorites.

Although I am unfamiliar with the actual distillation process, one thing I do know for certain is that awamori is made from Thai-style long-grained Indica rice rather than the more common short-grained Japonica rice that is used in the distillation of rice shôchû (kome shôchû). Japan has strict limits on the importation of rice from the U.S. and most other countries; rice from Thailand, however, is permitted, presumably to satisfy the demand of awamori makers for it. And as the label on the bottles will inform you, black koji mold, rather than the white variety more commonly used in shôchûproduction outside of Okinawa, is employed to “saccharify” the rice, that is to hydrolyze the polysaccharides in the rice into soluble sugars.

That, I’m afraid, is the extent of my knowledge of how the spirit is made. Now, about how awamori makes me feel, I could write volumes.

One more interesting factoid: awamori is said to have its origins in lao lao, (lit., Laotian alcohol) a rice whisky still produced in Laos. Awamori, then, is not merely a drink that will put hair on your chest, but also a vestige of the extensive maritime trade once conducted by the Ryûkyû Kingdom during its heyday in the 15th and 16th centuries. (Click here for more on the history of the kingdom.)

Incidentally, many people, including myself at one point, confuse Laolao, which is made from rice, and Mehkhong Whiskey from Thailand, which is in reality a kind of rum and made from 95% sugar cane. Mehkhong is a real winner of a drink, highly recommended, though it can be somewhat of an acquired taste.

So, we didn’t get to any shuzô while we were in Okinawa, but that didn’t stop me from drinking myself silly most nights.

We stayed at an excellent hotel called the Kafuu Resort Fuchaku Condo Hotel. As the name suggests, all rooms are “condo style”, meaning they come with a small kitchen, which is perfect if you have a small child with you and need to prepare its meals yourself.

What made the hotel really stand out, however, was the service and—here comes a big word—munificence.

The service: every morning when I went out for my “run” (read: chance to ogle young women in bikinis on the beach), I would find a work detail of some five security guards and other hotel staff out in the parking lot wiping the guests’ cars down because it had rained during the night. When my wife had a headache, they provided aspirin for free. When my son had a fever, they brought us a thermometer. Room service was quick and reasonable. They even had a “cocktail express” that would deliver drinks to your room in about five minutes.

That brings me to the generosity, the munificence of the hotel. There were no Gotchas!that seem to be the bread and butter of the hotel industry in the U.S. Wi-fi? Not only was it free, but the bellboy came to the room with a special wi-fi adapter for my MacBook Pro. Dishes and utensils, pots and pans for cooking? Free! Some items came with a modest fee attached to them, but for the most part most of the things we requested were provided free of charge, availability permitting. The vending machines in the hallway did not have the usual inflated hotel prices; they were the same prices you would expect to find at any vending machine. Food from the room service menu was also reasonably priced, so much so that we did not hesitate to have at least one meal a day delivered to our room. At the end of our five-day stay, the room service bill came to only fourteen thousand yen ($184) in spite of all Daddy's drinking.

One the second floor of the hotel was a small shop, a convenience store of sorts, that had among other things a good selection of awamori. The hotel also had its own brand of awamori which I tried on day one. Unfortunately, I don’t have the foggiest recollection of how it tasted. (Two and a half stars.)

The first bottle of awamori I bought downstairs was Matsufuji, a brand I had often seen at my local Washita Shop but had never tried. Matsufuji was alright. Didn’t knock my socks off, but it did do the trick: after polishing off half of the bottle, I was happily sawing logs.

松藤 (Matsufuji Awamori)

30% Alc/Vol

Rate: ★★★

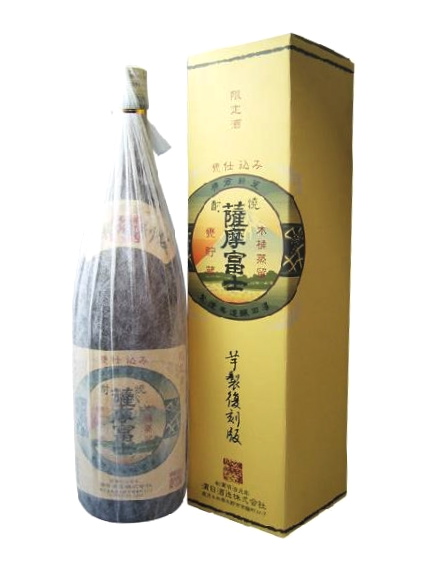

龍

Tatsu

There was also a pretty good bar on the second floor.

The first time I went I got so sozzled on cocktails that I ended up scribbling my apartment number back in Fukuoka, not the room number, on the tab. Fortunately, I realized my mistake and had him recharge the drinks to our room the next day.

The bartender took it in stride. “It often happens,” he said.

This bartender was not only a decent person, but could also make a pretty damn good drink, which brings me to one of my pet peeves: bartenders in the States. In America, many states require you to have a bartending license to work behind a bar. Does this make you a better bartender as the Professional Server Certification Corporation claims it will? No. What makes a great bartender is not a piece of paper and a few weeks of “mixology” classes, but experience, good sense, a love of fine alcohol and food, and a reluctance to skimp, the very things that many American bartenders lack. In the U.S., where so many bars are more often than not suction cups on the tentacles of massive corporations, there is an insidious push to cut costs wherever possible. And so, in the country that once exalted the cocktail, raising it to an art form, the well drink and crushed ice now dominate.

Anyways, on our third day in Okinawa, I slipped out of the hotel room while my wife and son were napping to get a bite to eat. There was a taco stand about fifteen or so minutes down the road that I had seen the day before and was interested in trying out, so I hiked up Route 58 (“Goya”). Unfortunately, when I got there, I discovered that the shop was closed for the day. (Let me tell you, this has happened to me so often I am just one teikyûbi, or “scheduled holiday”, away from going postal and shooting up the next shop that inconveniences me.) While I was out, though, I was lucky enough to bump into for the second time in as many days what is possibly the most gorgeous woman I saw all summer. Drop dead-beautiful, tall, slender and tan, she had a pair of knockers that would go on to torment me in my sleep. It made the otherwise fruitless trek more than worth the while.

I had been taking a walk with my son when I first laid eyes on the beauty. She was with her dog, wearing shorts and a tank top bra, her tits jiggling deliciously.

“How do you like them apples, son?”

Today, she, like me, was alone, and as we passed, our eyes met. I smiled at her, she smiled back, and I damn near melted.

In my fantasy, I say something clever that stops her in her tracks. She turns around.

“Taco stand’s closed,” I say.

“You’re not missing anything,” she tells me.

“No? Anything around here worth eating?”

“Only me.”

“Bon Apetit!” I say as she leads me back to her apartment.

Returning to the hotel, I dropped in at the bar. The bartender was polishing glasses.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Crowe.”

“Good afternoon.”

I took a seat near the window. The late afternoon sun was coming in through the blinds, intense and hot.

“Would you like me to close the blinds,” the bartender asked.

“No, no. I prefer it this way.”

For a people who supposedly worship the sun goddess Amaterasu, the Japanese sure do shut out the sun an awful lot.

“Bathe me in your warmth, oh Sun!” I say. “Dazzle me with your brilliance! Tan me! Make me as brown as a nut!”

“Would you like something to drink?”

“I would indeed,” I replied, squinting up at the bartender who had a halo of sunlight around him. I asked if he drank awamori.

He did.

“So, what brand do you drink?”

Tatsu was the answer. “I’ve been drinking it a lot recently.”

“Don’t believe I have ever tried that. Tatsu for me, then.”

“How would you like it?”

“On the rocks.”

“Certainly. I’ll be right back with your drink.”

The first time ever that I drank awamori was well over a decade ago in a past life, of sorts. It had been during my very first visit to Okinawa where I was traveling with a woman who would in less than two years’ time become my wife. (God help the two of us.)

As our room was being readied, we sat down at the lounge and had “welcome drinks”. While I can’t recall what my girlfriend had that afternoon, I will never forget what I ordered: awamori.

I may not have even heard of the drink before then and most likely selected it because it was the locals drank. When in doubt, it doesn’t hurt to ask.

Sitting there in that lounge and looking through a wall of glass at the clear blue sea—like nothing I’d ever seen before—I took my first sip. The signature flavor of awamori filled my mouth—like nothing I’d ever tasted before—and I knew it was love.

Since then, awamori has been my drink of choice in the summertime and I have tried several dozen brands. I am by no means a connoisseur of the drink, but I know what I like when I have it and I really liked Tatsu. There are better brands, of course—Seifuku from the island of Ishigaki is still my favorite—Tatsu, though, is a keeper, something that my ideal bar would have on its lower shelf.

Kampai!

龍 (Tatsu)

30% Alc/Vol

Rate: ★★★★