Before I tell my story, let me explain a little about my hometown, Nogata City. It is located in Fukuoka Prefecture which is itself on the island of Kyushu in the southwest of Japan. The city has a peculiar history, which is unique in Japan. Thanks to the coalmining business, it enjoyed prosperity for a time when coal was king, and then when the mines closed, the boom was suddenly over. One moment the city was full of life; the next, it was quiet, much like the fireworks in the night of a mid-summer festival.

Despite its small size, the area is geographically diverse. There is Mt. Fukuchi, which is about 3000-feet high, and the Onga, a major river in Japan, which calmly winds its way through the valley and empties into the Sea of Hibiki. The climate is influenced by the basin geography, so it is muggy in summer and bitterly cold in winter.

The size of town is 8,105 acres and the population was about 56,000 in 2020, having peaked in 1985 and steadily declined thereafter. The main industries were small retail and manufacturing subcontracted from the big industrial complexes in Kitakyushu which lies just north of Nogata. With the closing of the mines in the ‘60s and ‘70s due to cheaper imported coal, the local economy suffered and many businesses struggled to stay afloat.

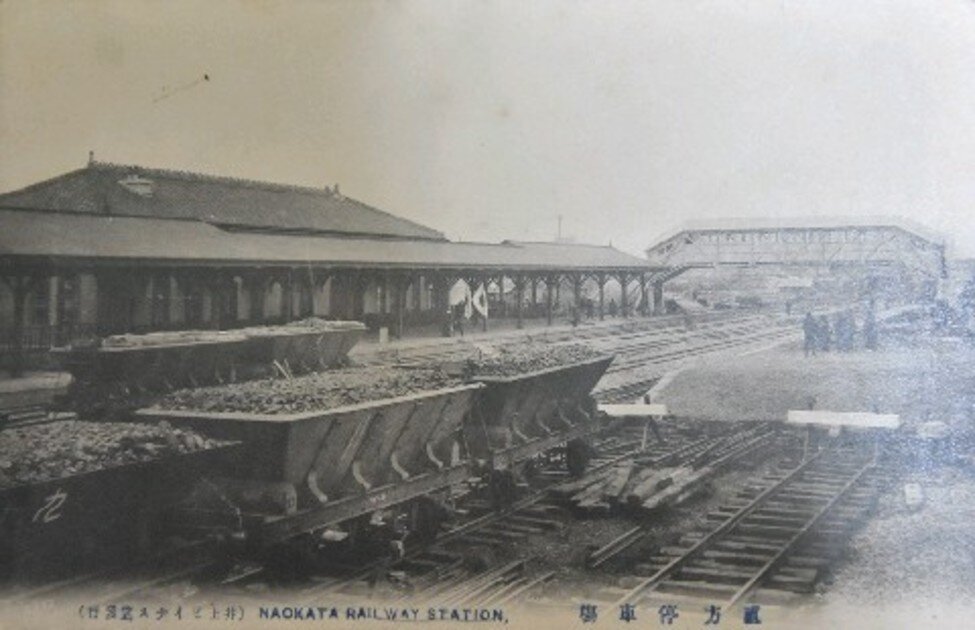

The heyday of Nogata began with the inauguration of the policy “Rich Country, Strong Army” by the government after the Meiji Restoration. The local coal mining business was suddenly in the spotlight and the city became the hub for the transportation of coal out of the region. Boats on the Onga River and trains on the Chikuho Main Railroad played an active part in carrying coal to the Yahata Iron-Works in Kitakyushu. The most prosperous period in Nogata was during the Russo-Japanese and Sino-Japanese Wars in the late 1800s and first half of the 1900s. People came and went, including miners, ferrymen, geisha—who were a highly trained entertainers and prostitutes—yakuza gangsters, and others who hoped to profit from the boom in business. Thanks to unique characters like them, the town’s freewheeling culture took root. There was an atmosphere of sexual freedom and openness that one didn’t find in more respectable places.

It would be remiss of me not to mention the topic of unlicensed prostitutes. The town, which was infested with hooligans and other young troublemakers, reflected the town’s way of life. It is said that there weren’t any bills smaller than the 5-yen note in Nogata at that time, meaning that people didn’t care about small amounts of money and were rather spendthrift. Miners blew all their money in a single night on gambling and women. They made a fortune in the dark mines and had money to burn. This led to liberal attitudes towards sex. Many women who had been sold by their parents in order to help their families make ends meet, were sent to the town to work. Men, who could not contemplate their futures when they risked life and limb every day in the mines came to Nogata to spend their money on pleasure.

In the years just after WWII, Japan was still in chaos, both socially and economically. Steam locomotives still came and went and Nogata was terribly sooty, with the smell of the coal-burning trains hanging heavily all over town. There was a yawning gap between the rich and poor and the sense of right and wrong had been corrupted. Only money prevailed. Those who didn’t have it would do anything to get it; and those who had would do whatever it took to keep it. It was truly a dog-eat-dog world. And it was in this world that I was born in 1948 and where I spent my childhood.