Learned a new word today: 立志式 (risshi-shiki)

りっししき 【立志式】

【説明的に】a ceremony for fixing one's aim in life.

The Risshiki Ceremony is a ceremony for students to talk about their dreams and goals for the future, and to become aware of their responsibility as adults. It is an opportunity for junior high school students in the middle grades to reconsider their way of life and aspirations.

The origin of the Risshi Ceremony is the “Genpuku Ceremony” (元服) which was once held as a rite for becoming an adult. It is often held at the age of 14, when the mind and body are believed to be undergoing the transition to adulthood, and is positioned as the first step toward adulthood.

At the Risshiki Ceremony, students present their resolutions and dreams for the future. Parents and guardians may also observe the students' presentations.

Keio JR High School’s Entrance Exam

Are you smarter than a 6th grader?

An on-again, off-again student of mine recently entered Keio University. A Keiko U. High School student, he didn't have to take the entrance exam as all students are guaranteed a place at the prestigious university. As a result, he didn't really study that much in junior and senior high. He couldn't, for example, name any of Natsume Sōseki's novels when we talked about the author the other day.

He did, however, study his nuts off in elementary school. From the fourth grade to the sixth grade, he attended juku (cram school) seven days a week. He said, he would wake up early in the morning study for a few hours at home, then go to school where he played with friends. Immediately after school, he would run off to the juku to attend several hours of classes. Upon returning home in the evening, he would have dinner, take a bath, then resume studying until he conked out at midnight.

All the effort paid off--he got into Keio Jr High and was set for the rest of his life.

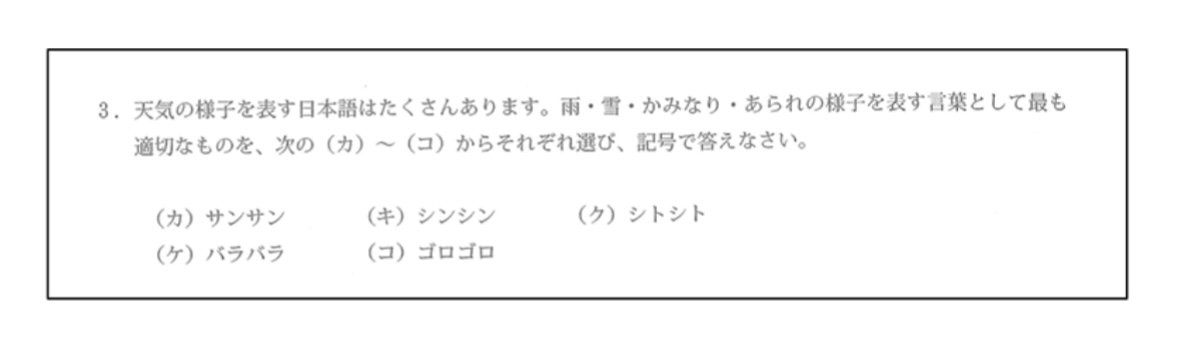

Pictured are some of the questions from Keio JH's entrance exam. For an adult, they are not that difficult. If you have a lot of different experiences and have read books and been curious, you can solve them. (I could, at least.) For a 12-year-old, however, they must be staggeringly difficult.

Usui

Usui 雨水 Yǔshuǐ (19 February ~ 5 March)

According to the traditional Chinese calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms (jieqi, 節氣 in traditional Chinese; sekki, 節気, in Japanese), Usui (雨水, Yǔshuǐ in Chinese) is the second mini season of the year. Lasting from roughly February 19th to March 5th, Usui means “rain water”. It is the time when the first day of spring has passed and we begin preparing for the arrival of full-fledged spring. Falling snow becomes rain, and the snow and ice that have accumulated over the past several weeks melt and turn into water.

Kasumi 霞

The phenomenon in which distant objects appear blurry due to water vapor in the air and the faint cloud-like appearance that appears at this time is called kasumi, or “haze”.

Although similar to fog (霧, kiri), it is usually called kasumi in spring rather than kiri, which is the term usually reserved for the mist that occurs in autumn.

春なれや

名もなき山の

薄霞

Harunare ya

Namonaki yama no

Usugasumi

“Spring and the thin haze of a nameless mountain”

This is a haiku by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), the famous haiku poet from the early Edo period. Looking at the thin mist that hangs over the nameless mountain, you can see that spring is in the air.

The ethereal haze hanging over the foothills of mountains and lakes can sometimes appear otherworldly, magical.

Nekoyanagi 猫柳

The Pussy willow is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Salicaceae family, which produces dense silvery-white hairy flower spikes in early spring.The flower spike of the pussy willow resembles a cat's fur, which is—no surprise—how it got its name.

Known as neko yanagi in Japanese (猫柳, lit. “cat willow”), the plant is also called senryu (川柳, lit. “river willow”) because it often grows alongside rivers.

The haiku poet Seishi Yamaguchi (1901-1994) wrote the following poem.

猫柳

高嶺は雪を

あらたにす

Nekoyanagi

Takane wa yuki o

arata ni su

“Takane Nekoyanagi renews the snow”

The silver-white fur of the nearby pussy willow shines, and perhaps the high mountains in the distance are covered in fresh snow and shine brightly. This haiku conveys the signs of spring and the harshness of the cold weather that tightens the body.

Are Kinome and Konome the same?

Although written with the same kanji, 木の芽, konome refers to the buds of trees in general. Read kinome, it refers only to the buds of Japanese pepper (山椒, sanshō).

In recent years, the two are often used interchangeably, but in the past they were used separately.

Is “Doll’s Festival” an event for girls?

March 3rd is the well-known as the Doll's Festival, or Hina Matsuri (ひな祭り). It is also called Joshi no Sekku (女子の節句)

In ancient China, there was a custom to purify oneself in the river on the Day of the Snake in early March. This is known as Jōshi no Sekku, ( 上巳の節句) and is believed to be the root of Hinamatsuri.

It is said that this festival was introduced to Japan during the Nara Period. Over time, Japanese began transferring their impurity to dolls made of paper or straw and then sending them adrift in a river (流し雛).

As time passed, these dolls began to be displayed on doll stands, and the festival evolved into the Doll's Festival.

March in the lunar calendar is also the season when peaches begin to bloom, which is why the other name Momo no Sekku (桃の節句, Peach Festival) was born.

Today, the Doll's Festival is as an event to pray for the healthy growth of girls. Until the Muromachi Period, however, it was a festival to pray for the health and safety of not only girls but also boys and adults.

Translated and abridged from Weather News.

Love Hotels

Hard to believe that Fukuoka has a less than average number of love hotels. Shame on us.

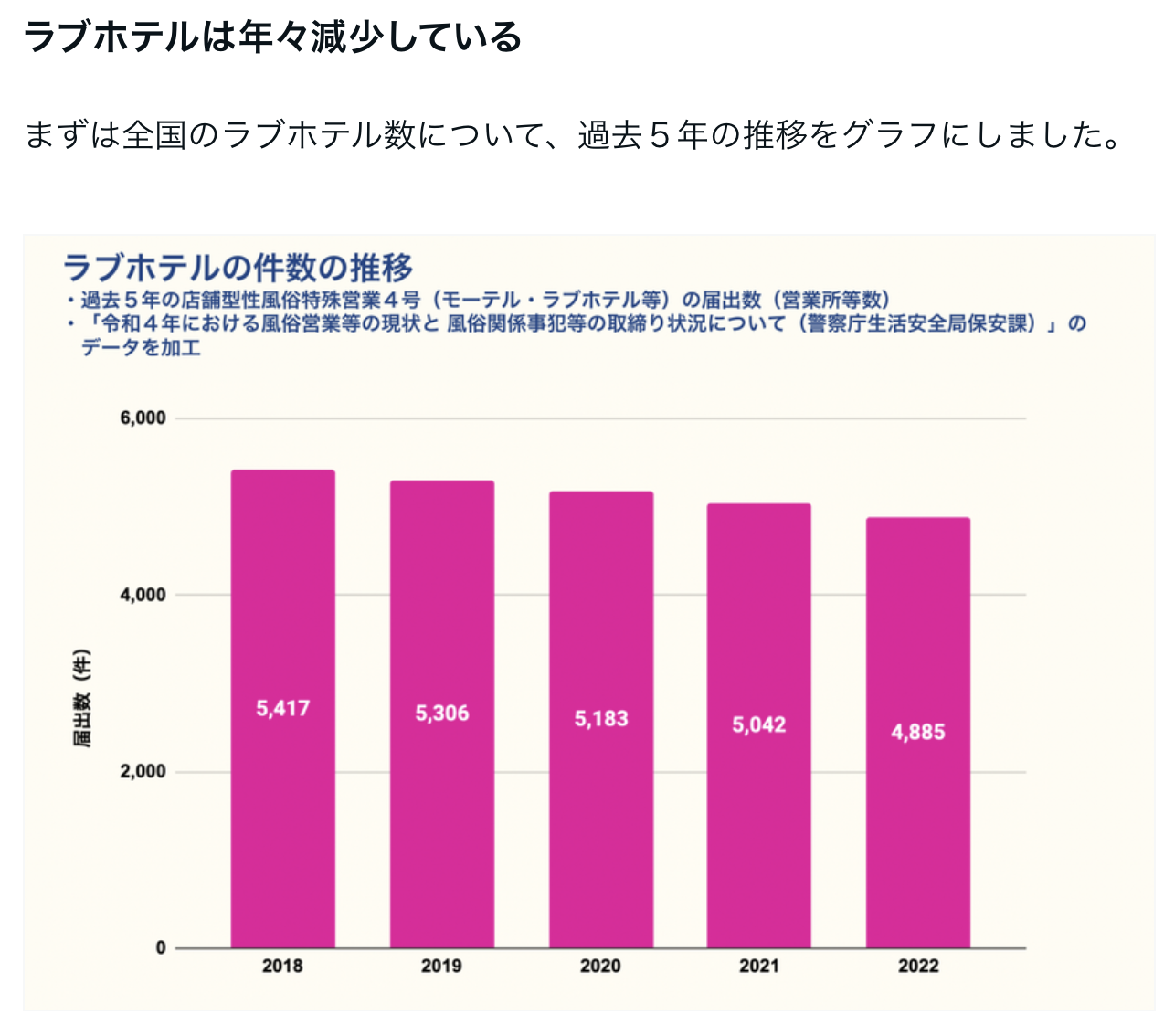

The number of love hotels nationwide is (or was at the time of the original post) 5,670, or 5.39 hotels per 100,000 adults.

Miyazaki Prefecture has the highest number, with 14.08 per 100,000 adults (deviation value: 72.4). Second place was Saga Prefecture with 13.28 houses. From here on, to be known as “Saucy Saga”. Third place and below are Fukushima prefecture (12.50), Kumamoto (12.21), and Tottori (11.70). Begs the question what is going on in randy old Kyushu.

On the other hand, Hyogo Prefecture has the lowest number of hotels—only 0.84 per 100,000 adults (deviation value: 28.8). This is followed by Kanagawa (1.78), Aichi (2.70), Tokyo (2.73), and Saitama (3.35). Sad.

Incidentally, the very first rabuho I ever went to happened to be in Kumamoto. It was called DINKS, a term I hadn't heard of before. I asked my girlfriend what it was supposed to mean and she replied matter-of-factly, "Dual-Income, No Kids". The poor girl’s English wasn’t very good, but for some reason she knew that term. It just rolled off her tongue like she had said it a hundred times before.

(By the way, "DINKWAD" means "Double income, no kids, with a dog". A lot of my friends are DINKWADs.)

According the site note, the number of lover hotels has been gradually decreasing every year. In 2018, there were 5,417 establishments, but in 2022 the number had fallen to 4,885. It is estimated that around 100 love hotels go out of business every year. There seem to be a variety of factors contributing to this, including population declines in local cities, young people moving away from cars, and stricter regulations by local governments.

For more, go here.

Officer Friendly still exists in Japan

Heiwa Desu Ne

In the wee hours one morning in November, I was woken by the sound of a police car siren. Living downtown, disturbances in the middle of the night are not uncommon, but this night was different. The police car sounded as if it driving slowly up and down the streets around my building, siren blaring on and off.

Unable to sleep, I got out of bed to see what the commotion was all about.

I stepped out onto the balcony and looked down at the street below, but couldn't find anything amiss. But then came wail of the siren again. This time from the west and only a block away. I went to the living room and looked out the window in the direction the sound had come, but was still unable to see anything.

What on earth was going on? I wondered. The siren had sounded so close.

Ah, there it was again. This time, I hurried out the front door to get a better look. The siren was growing louder.

Standing on the stairwell and looking down the narrow road that passed the rear of my building, I discovered a young man on a bicycle. He was riding one of those electric bikes with the fat tires that look more like off-road motorcycles than your typical mamachari. He headed down the road in my direction. A patrol car, its lights flashing, came around the corner in leisurely pursuit.

Judging by the way the bicycle was weaving, the rider was slightly drunk. When he turned onto a wider road, the patrol car pulled up even with the cyclist.

"Please stop!" the police officer called politely over the PA system.

The patrol car then pulled ahead, attempting to cut the cyclist’s off.

"Please stop!"

Did the guy on the bike stop?

Nope, he just pedaled around the front of the police car, then turned down a narrow alley and continued on his merry way. With its lights flashing, the patrol car sped down the road and was about to turn off onto a side road but ended up getting blocked by a taxi.

I have no idea what happened after that, but judging by the silence, the drunk cyclist probably managed to slip away.

I couldn’t help but chuckle.

As long as I have lived here—thirty years and counting—the Japanese have been wringing their hands and fretting about the alarming trends the see on daytime wide shows and in the evening news. Perhaps it’s just part of the national character. But, you know, from my perspective, things are pretty darn good here.

Despite how people may feel about crime, the police’s own statistics paint a very different picture: “the total number of known cases of penal code offenses has decreased consistently since 2003. In 2021, the number was 568,104, the lowest since the end of the Second World War . . . In 2021, the rate of decrease was 7.5% over the previous year, which was lower than the level in 2020 when COVID-19 broke out.” (National Police Agency: “Crime Situation in 2021”)

Did the pandemic influence those numbers? Probably, but crime had already been on the decline since peaking in 2002. It was in the years leading up to 2002 that the “Dankai Juniors”, the cohort of Japanese born in the seventies were in their twenties and unemployment was over 5% — the Employment Ice Age (Shūshoku Hyōgaki), as it was known.

As for violent crime, why it’s so rare here that when it does on occasion happen, the more shocking cases tend to get ruminated on in nation's news shows for days if not weeks. On that sleepless morning back in November, America recorded its 500th mass shooting of the year. By comparison, there was only one shooting death in Japan in 2021. Murders, and violent crime in general, have fallen steadily since the sixties. There were 213 murders that same year, compared to over 21,000 in America. I know, apples and oranges. Then, consider England and Wales which has a population about half that of Japan’s and fairly strict gun laws. In the 2022/23 reporting year, 602 homicides were recorded, down from 697 in the previous year.

You don’t see homeless people camped out on the streets like I did all over California last spring. LA alone has some 50,000 people sleeping rough and over half a million (582,000) nationwide. In the UK, there are 365,000 homeless; in Germany, 263,000; and in Canada, 235,000. Among Japan’s neighbors, China has over 2.5 million homeless; Korea, over 11,000. In Japan, there are only 3,065, down 11.1% from last year. My adopted home of Fukuoka prefecture has just over 213 homeless, but you’d be hard pressed to actually spot any of them.

Although marijuana use among university “American football” players has been a hot topic in the news since last summer, the fact remains that drugs haven’t really been a serious problem in Japan since the end of WWII. There were, for instance, only a handful of arrests (3) in the most recent data related to heroin. Compare that to the opioid crisis in the US which has claimed over 645,000 lives due to overdoses and, well, there just is no comparison.

And because it’s so safe, stores in Japan needn’t worry about getting cleaned out by shoplifters or opportunistic rioters like they do in the US and last September in France. Cars rarely get stolen. (Bicycles, do, but if you report it to the police, they might find it in a few months just like they found my son’s bike, god bless ‘em.) Homes seldom get broken into. But, when they do, the culprits are usually found, occasionally perp-walked on national TV, then prosecuted and punished fairly swiftly.

No, Japan has the kinds of problems other nations wish they had.

Stepping back into my apartment, I discovered my wife at the genkan.

What happened, she asked sleepily. When I told her about the drunk cyclist playing cat and mouse with a patrol car, she laughed and said, “Nihon wa heiwa desu ne.” Japan’s a peaceful country, isn’t it.

“Ain’ it?”

And with that, I went back to bed and fell fast asleep.

Kotatsu Envy

What percent of homes have a kotatsu?

Ranking of those who "dream" of having a kotatsu.

1位 沖縄 (Okinawa) 63%

2位 北海道 (Hokkaidō) 60%

3位 東京 (Tōkyō) 53%

4位 神奈川 (Kanagawa) 50%

5位 愛知 (Aichi) 48%

No. 1 is easy to understand. In Okinawa, it never gets cold enough to need one. When we were shivering in freezing weather with a windchill of -4℃ a few days ago, it was about 20℃ in Naha.

No.2 Hokkaidō is interesting. Why would they long to have a kotatsu? Well, the reason is because they don’t need really them. For starters, homes and apartments in the northernmost prefecture are built for the local climate—i.e. better insulation, double-glazed windows, etc.. What’s more, heating is subsidized. (Need to fact check that.) My wife, who used to spend her winter breaks near Sapporo every year, remarked that even the room the toilet was in was always nice and toasty.

Meanwhile here in Fukuoka, I’m wearing my “longjohns”, have got the heater and electric carpet on high and I’m still cold.

Popularization of the Washlet

Ah, 1992. Aye, those were hard times when only 20% of homes had toilet that lovingly squirted your fanny with warm water. Japanese kids today don't know how easy they've got it.

Selling Snake Oil

After cocktails and hors d’oeuvres, a fifty-something-year-old American man, someone I have never seen around town, taps on a microphone a few times then jumps right into his presentation.

From the get-go, it stinks of some multilevel marketing scheme and, looking around the room, I can see that it’s the same old crew that has come together to push it: guys who were doing Amway, then NuSkin, then Noni. And now they’re gung-ho about something called Rexall Showcase: a new name to the old scheme of pushing overpriced supplements and dubious weight loss products on family and friends and kicking the profits up the pyramid.

“This is the opportunity you’ve been waiting for, folks!” the speaker exclaims. “This is The Golden Opportunity! The chance to get into a business when it’s just getting off the ground. Amway, NuSkin, yes, they’re all good business models, excellent business models, in fact, but if you really want to make money with them, why, you should have gotten into the business twenty, thirty years ago. Folks, I’m tellin’ ya, Rexall Showcase is the opportunity you’ve all been dreaming about!”

As I listen to him, I must admit that what he is saying doesn’t completely lack merit. Imagine being able to have entered into a business like Amway when it was first taking off, before overeager fools irretrievably ruined its reputation. But today? Try to become a millionaire in Amway today and you’ll probably die trying. Your hair and skin will look fantastic, though. You might even feel fantastic, too, if you can manage to swallow their horse-pill sized megavitamins.

The American tells us he has been living in Japan for over thirty years, longer than anyone else in the room. “I’ve been here since Nixon was president!”

Laughter.

“And all these years, I have been running a business. Several businesses, in fact!”

He’s quite successful, he assures us, saying that he even supplies Fukuoka Airport with his products.

There are oohs and ahs.

“And, let me tell ya, folks, I know a good opportunity when it comes up from behind me and kicks me in the ass.”

More laughter.

The American talks like a snake oil salesman, but the others in the room eat it up; so eager they are to get their grubby little hands on cold hard cash that what he is saying must sound like the sweetest of music to their ears.

And then, he invites a long-haired douchebag by the name of Clive up to the front and says, “Clive has been blowing us away . . . Tell me again, how much did you earn last month?”

“Two million yen.”

There are whistles of astonishment and why wouldn’t there be? Two million yen for a month’s worth of work is a respectable amount of cash, twice what I am making, working what amounts to three jobs. But, why is this “very successful” guy dressed like someone who is only earning a tenth that amount? The Canadian, a former strip dancer at a “ladies’ club” that went bust years ago, is wearing ripped Levis, old cowboy boots, and a dowdy sports jacket. Any moment now I expect him to tear the jeans off and start jiggling his nuts.

“See, I told you it was fishy,” Akané whispers into my ear.

“Fishy doesn’t even begin to describe it. This is borderline fraud what they’re doing. Let’s get out of here.”

This is an excerpt from A Woman's Hand, a sequel of sorts to the novel A Woman's Nails. The novella was inspired by events which happened about fifteen years ago.

Lanterns of Kyoto

The red lanterns hanging from the eves of machiya in Gion and neighboring areas of Kyōto indicate which of the five hanamachi (花街, lit. “flower town”) or geiko communities containing o-kiya (置き屋, geisha houses) and o-chaya (お茶屋, teahouses) it belongs to.

Centurally located Gion Kōbu, through which the main thoroughfare Hanami Kōji Dōri runs, has red lanterns with a white kushi dangō design, i.e. linked circles in a horizontal line around middle of the lantern. The lanterns of Kami-Shichiken (上七軒), the oldest of Kyōto’s hanamachi and located near Kitano Tenmangū shrine in the northwestern part of the city, feature the inverse: linked red circles on a white background. Across the Kamo River in Pontochō, the lanterns feature two red birds, and so on.

Gion Kōbu 祇園甲部

Gion Higashi 祇園東

Miyakawa-chō 宮川町

Ponto-chō 先斗町

Kami-Shichiken 上七軒

Hanamachi Map

Cobwebs

Japan, you are one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world. Surely, you can come up with a better way of wiring your nation than this.

A comment by “Jeffery” from my other blog:

“I hate overhead power and communication lines. They are used too much in the U.S., though many counties and municipalities have begun to require that they be buried during new construction. Europeans look at it like we're India.

”Last job in Japan was in residential housing. I remember seeing RE fliers for projects I was familiar with and all the photos had the power lines Photoshopped out. So, even the Japanese admit that they are unsightly to say the least.

”One Japanese excuse I've heard is that it's done because of typhoons and earthquakes, which are actually the very reasons you bury them - less likely to have them disturbed during these than if they are on a pole that comes down disconnecting several square blocks in the process. Another whopper is about high water table, which is nonsense since most much of the new construction in Tokyo is on "reclaimed" land and they manage to bury it all there.

”But, hey, public officials in tornado and hurricane country in the U.S. are just as deluded not insisting that they be buried so that they aren't torn to pieces every other year or so.”

Hanako Nippon

Those of you who have been paying attention may have noticed that the photo on the sample driver’s license of “Nippon Hanako” has changed. The older version featured a woman who was quite “bubbly” in appearance—looking like she had just finished work as an OL and was going to change into a revealing “body-con” outfit and feather boa and go dancing in Roppongi.

Although most of the information is the same, the birthdates are different. The elder Hanako was born in 1965; the younger in 1986, making her considerably younger: 35. And, where, the older Hanako was permitted to drive all sorts of vehicles, what is known as “furubitto”; the younger one’s license is somewhat limited.

Ms. Nippon is a model, of course, and a rather nice-looking one at that. The photo on the sample license doesn’t do her justice.

I happened to watch an interview of the model on TV a few weeks ago during which she said something that struck me as both amazing but also very Japanese. Although she has a driver’s license, she admitted that she doesn’t dare drive herself because she is afraid of having an accident and having her name and pseudonym plastered all over the news. “It just wouldn’t be right if Nippon Hanako caused an accident, would it?”

So, how does Hanako get around herself? By bicycle.

The Right Stuff?

This morning, the right wing nuts were out in force, kicking up all kinds of noise and playing "gunka" (military songs) over their massive loud speakers.

We happened to be at the same intersection where they were stopped at a red light. My elder son, as he crossed the street, paused before one of the buses and gave it a long hard look. When he got near me, he asked:

"What the hell was that? Something to do with Karate?"

I burst out laughing, but understood why he was confused: the symbols and logos employed by various karate dojos can be awfully similar to those used by the uyoku (right wing) here. And the parents of kids doing karate look like just like the shady characters you find driving the gaisensha (sound trucks).

Destine

This should do the trick.

Ten years ago I started really traveling Japan rather than just living here. On my first visit to Tokyo in a decade I happened to pass by a Uighur restaurant. It then occurred to me that if Tōkyō had Uighur, they might have Lebanese, too, and, hey presto, they did. As I drank an Almaza beer, I got a strong hankerin’ fer a narghile. Another GoogleMap search and I learned that there was a shisha cafe in a place I’d never heard of before called Shimokitazawa. So, I popped over there and, boy, what a discovery. I had been smoking at home on my own narghile for over five years, but had never come across any places that had it in Japan. The place in Shimokita was Japan’s very first and I would be dropping by there regularly over the next decade.

I quickly learned that that if I did a search of ‘“mizu tabako”, I’d find an interesting place with cool people, but not as cool as the ones I met in Shimokita. Still, cool ‘nuff.

An’ so, that’s how I found Jajouka in Kyōto and Destine in Ōsaka. Now, 10 years later, I am still coming. Staff have become friends in the meantime. Love this place!

Destiny!

Carnations For Moms

In Japan, everyone gives carnations on Mother’s Day. If you ask why, they shrug. Some might say that carnations are a symbol of mothers. Ask why, and they'll shrug again.

The thing with "traditions" in Japan is that a lot of them are imported. And, more often than not, the country from which the custom was adopted has itself long stopped doing it. The traditional school uniform for boys here is a high collared black jacket with buttons down the front. This came from Prussia over a hundred years ago. The sailor uniforms, too, were adopted from, I think, the clothes a British prince was wearing a century ago and the principal of a school I worked for adopted it as the school's uniform. It took off from there, becoming standard in Japan.

Mothers Day was also imported, most likely from the US, introduced in the postwar years by Christian missionaries. There was a different Respect Mothers Day that was the birthday of the Empress before the war, but like many of the pre-1945 holidays that were related to the Emperor they got thrown out or repackaged.

So, again, I suspect that Christian missionaries brought the custom of giving carnations to mothers on Mother’s Day. Why carnations? Because legend has it that carnations started to grow where the Virgin Mary's tears fell when she saw Jesus carrying the cross pass by.

I had never heard of this and looked up the Stations of the Cross to see if there was any mention of it. The 4th Station of the Cross (Traditional) is where Jesus meets his mother. Nothing about carnations or flowers there, so I still don't know how that all got started.

From Wiki: "Out of the fourteen traditional Stations of the Cross, only eight have a clear scriptural foundation. Stations 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9 are not specifically attested to in the gospels (in particular, no evidence exists of station 6 ever being known before medieval times) and Station 13 (representing Jesus's body being taken down off the cross and laid in the arms of his mother Mary) seems to embellish the gospels' record, which states that Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus down from the cross and buried him."

Chabitsu

Learned a new Japanese word yesterday: 茶櫃 (chabitsu).

Most chabitsu today are squat round wooden containers for keeping sencha (煎茶, medium grade tea), but 櫃 (hitsu) originally referred to large wooden lidded chests used for storage. This one is used to store antique kimono.

Kakeibo: Making Ends Meet in Japan

I am a big fan of the Nobuko Takahashi Kakeibo[1] Clinic, an advice column published in Fukuoka’s Living Magazine, and have been reading it for many years. In the column Ms. Takahashi answers personal finance questions posed by Japanese housewives and gives advice on how to deal with the challenges facing their families. It offers an unusually candid look into the personal finances of the typical Japanese family.

In one of her more recent posts, a 28-year-old housewife and mother of a five-month-old baby girl wonders if it might be better to buy a house sooner rather than later.

The housewife writes:

“My husband and I married two years ago. Wishing to devote myself to raising our child, I quit my job and became a stay-at-home mother. Compared to when my husband and I were both working, our income is now half what it used to be. Although I’m somewhat uneasy about our finances, I enjoy raising our daughter and, because our home is a happy one, it hasn’t been hard for us to cut down on expenditures.

“First off, we reduced our pocket money and took a second look at what we had been spending on our cellphones. We seldom, if ever, eat out, and are able to economize by cooking for ourselves at home. Large expenditures, such as insurance are paid in annual installments and we’re trying reduce costs wherever possible. We also put aside a little every month. My husband’s varies by as much as 100,000 yen a month depending on how much overtime pay he earns. Our expenses, on the other hand, are fairly stable at the amounts I have indicated below.

“Recently, my husband’s parents have suggested that we build a house near theirs and we’re now thinking of buying one in the near future. I’ve heard, among other things that the tax deduction for homeowners will be reduced and the tax on property increased, so I’m wondering if we should make haste in buying a home or wait. Also, how much cash should we put down? We’re taking another look at our insurance premiums to see if we can save money there. We look forward to hearing from you.”

Mr. & Mrs. T of Kitakyūshū City

Husband (31), Wife (28), Daughter (5 months)

Income

Husband’s monthly income 240,000 yen

Children’s allowance from government 13,000 yen

253,000 yen per month

Rent 58,000 yen

Food 26,000 yen

Utilities 18,000 yen

Cellphones (2) 15,500 yen

Misc. 2,000 yen

Medical Costs 1,000 yen

Gasoline 20,000 yen

Entertainment 5,000 yen

Misc. 15,000 yen

Child Care Related Costs 7,000 yen

Husband’s Allowance 30,000 yen

Wife’s Allowance 10,000 yen

Wife’s Life Insurance 2,000 yen

Education Insurance 5,000 yen

Car Insurance 5,000 yen

Total 219,500 yen

Surplus 33,500 yen

Annual Bonus 960,000 yen

Annual Costs

Car Insurance (2 cars) 85,000 yen

Car Inspection 100,000 yen

Husband’s Life Insurance 38,400 yen

Educational Insurance 116,000 yen

Savings

Husband’s Savings (1) 2,200,000 yen

Husband’s Savings (2) 5,300,000 yen

Wife’s Savings 2,200,000 yen

Child’s Saving 200,000 yen

Before I go on to Takahashi's advice, I'd like to point out that the husband earns a modest annual salary of 3.8 million yen, or about $38,000 a year. The two of them, however, have ¥9.9 million (or $99,000) in savings. According to CNN/Money's net worth calculator, the average median net worth for an American in Mr. & Mrs. T's age group is only $8,525, and $34,375 for his income level.

Japan is commonly believed to be an expensive place to live as evidenced by melons selling for a hundred dollars each. But in actuality, it can be an easy place to sock your money away. Medical costs, thanks to an excellent national healthcare system are unbelievably low, rent is reasonable if you’re willing to compromise on location and size, public transportation makes owning a car with all its related costs unnecessary, and taxes are not very high.

Takahashi replies:

“Even though your income has been reduced by half, you still manage to run a monthly surplus and have already saved close to 10 million yen. What’s more, you have the goal of building your own home and are putting effort into saving money to that end. Keep up the good work.

“You asked when the best time to buy a house was. Earlier is not always better. It’s important to keep in mind that there are three periods in a person’s life when they can purchase a home.

“The first is when low interest rates, tax deductions, a fall in house prices, and so on make it advantageous for you to buy a house.

“The second is related to your life cycle. You should determine whether it is a good time to move by looking at the start of your child’s entry into a new school or the needs of your parents and so on.

“And the third, is by looking at your personal finances. Can you safely buy a home—have you got enough money to put up front and is your situation stable enough for you to afford to make payments?

“It is ideal when all three of these come together at the same time, but you should at least prioritize the second and third points. In your case, you need to check whether there is a chance that your husband will be transferred in the future, and you should think about your relationship with his parents. You should also look into how much more you are able to save from now on and how much you’ll be able to spend on a house. Until you do that, you won’t be able to determine how much you of a down payment you should make.

“You also need to be careful about rises in the interest rate, reductions in the deduction for homeowners, supply and demand, and so on. A fall in the supply of building materials and carpenters, for example, can cause the price of building a home to rise considerably, which makes it easy for construction companies to cut corners.

“You might want to also take a second look at purchasing some additional life insurance for your husband. If necessary, you can always work full time, but if you add a life insurance policy to your home loan, you can receive up to 10 million yen in the event that your husband passes away. Otherwise, you might want to take out another policy on your husband.”

Whaddya think?

[1] A kakeibo (家計簿) is a family account book. Any Japanese housewife worth her salt (almost wrote “worth her mustard”) will keep a detailed record of her family’s expenditures and keep a the purse strings tight.

Blessed

Back when I did a lot of translation work, there was a phrase that I was forced time and again to render into English: utsukushii shizen ni megumareta (美しい自然に恵まれた, lit. “blessed with beautiful nature”). I would translate it in a variety of ways, such as “The prefecture is blessed with bountiful nature”, “The city is surrounded by lots of natural beauty”, or “The town is surrounded by beautiful nature.” Or even, “It is located in an idyllic natural setting.” I found that if I took too much poetic license in my translations, they invariably came back to me with “You left out ‘beautiful’” or “You failed to mention ‘nature’ in your translation”. Whatever.

The thing that killed me when I was doing these translations is that I would look out my window at the jumble of telephone wires and cables, the lack of trees, the concrete poured over anything and everything that hadn’t been moving at the time, the gray balconies and staircases stretching as far as the eye could see and shout, “Where the hell is the ‘beautiful nature’? Tell me!! Where is it?!?!”

Having grown up in the west coast of the United States, I know what unspoilt nature is supposed to look like. In my twenty years in Japan, however, I have yet to find a place that has not been touched by the destructive hand of man despite having seen quite a bit of the country. Mountains that have stood since time immemorial are now “reinforced” with an ugly layer of concrete; rivers and creeks are little more than concrete sluices; and Japan’s once beautiful coastline is an unsightly jumble of tetrapods—concrete blocks resembling jacks—that are supposed to serve as breakwaters but do very little in reality.

The uglification of Japan has been well documented in Alex Kerr’s excellent and highly recommended books Lost Japan and Dogs and Demons.

"Today's earthworks use concrete in myriad inventive forms: slabs, steps, bars, bricks, tubes, spikes, blocks, square and cross-shaped buttresses, protruding nipples, lattices, hexagons, serpentine walls topped by iron fences, and wire nets," he writes in Dogs and Demons.

"Tetrapod may be an unfamiliar word to readers who have not visited Japan and seen them lined up by the hundreds along bays and beaches. They look like oversized jacks with four concrete legs, some weighing as much as 50 tons. Tetrapods, which are supposed to retard beach erosion, are big business. So profitable are they to bureaucrats that three different ministries — of Transport, of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and of Construction — annually spend 500 billion yen each, sprinkling tetrapods along the coast, like three giants throwing jacks, with the shore as their playing board.

These projects are mostly unnecessary or worse than unnecessary. It turns out that wave action on tetrapods wears the sand away faster and causes greater erosion than would be the case if the beaches had been left alone."†

One of Japan’s recurring problems is that once something has been set into motion it is often difficult to change course. As a result, by the early 90s more than half of Japan’s coastline had already been blighted by these ugly tetrapods. I dread to know what the figure is today.

One of first of my imaginary political party’s[1] campaign promises is to form a Ministry of De-construction that would remove unnecessary dams, tetrapods, concrete reinforcements, and so on. The idea is to put the ever so important general construction industry to work by undoing all of their mistakes. Second, where the dams, reinforcements and tetrapods were truly necessary, they would be concealed in such a way to look as natural as possible. Third, the electric cables would be buried. Fourth, there were would be stronger zoning and city planning to reign in urban and suburban sprawl. (Too late?) Create compact, highly dense cities that were separated from each other by areas of farming, natural reserves, and parks. (One thing I can’t get is how in a country with as large a population as Japan’s and land as limited put vertical limits on construction—Fukuoka City once had a limit of 15 stories). Fifth, reintroduce diversity to the nation’s forests. No more rows upon rows of cedar that not only look ugly, but give everyone hay fever in the spring.

Unfortunately, none of these things are bound to happen anytime soon. The Japanese are so accustomed to being told in speeches and pamphlets that their town or city is blessed with beautiful nature that they have come to believe it despite what they surely must see with their own eyes.

Familiarity sometimes breeds content.

[1] I call my party Nattoku Tô (なっとく党, The Party of Consent/Understanding/Reasonableness). It is a play on the sound of the local Hakata dialect and with the right intonation can me “You got that?” “Can you assent to that?”

†Kerr, Alex, Dogs and Demons: The Fall of Modern Japan, London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2001, p.289.

Hita, Oita

Hita, a small city located in the western part of Ōita Prefecture, was in olden times a tenryo town. During the Edo Period (1603 to 1868) tenryo towns were under the direct control of the Tokugawa Shogunate and charged with keeping an eye on the happenings of outlying feudal domains. In the case of Hita, it came under the direct control of the House of Toyotomi and oversaw all of Kyūshū.

The neighborhood of Mameda Machi in the center of Hita's old town was a major hub of politics and commerce in Kyūshū during the Edo Period.

Although the area has suffered three major fires over the centuries, many of the houses still look pretty much as the did in the early Edo Period, with their white washed walls and decorative wall paintings, called kotei-e. (Minus all the souvenir shops and busloads of tourists, of course.)

The umé were in bloom throughout the town, filling the air with their sweet fragrance. Even on a day as cold as today was, just seeing these blossoms remind you that spring is around the corner, so hang in there.

At first, I thought the wall of this house had been decorated with stones. On closer inspection, however, I realized that the "stones" were actually clay bricks.

Zōri, anyone?

A shop selling wood and bamboo crafts. I was more impressed with the handwritten signs on each item than I was in the actual merchandise.

I wanted to go inside this building, but my father-in-law was eager to push on.

A close-up of the same building.

The Kunchô Sake Brewery. Built in the Taishō Era (1912–1926), the design incorporates both traditional Japanese building techniques and western influences.

March third is Girls Day in Japan, (every day is Girls' Day in my heart), a day on which parents decorate their homes with traditional Heian Period doll sets (hina ningyō) and plum blossoms and pray for the safety and happiness of their daughters. Superstition has it that your daughter's marriage will be postponed if the dolls continue to be displayed after March fourth, so people usually take the dolls out of storage in February.

Throughout Hita you'll find hina ningyō on display in private homes, restaurants, and shops during the festival.

Milk Run

The other evening, I saw something that one rarely sees if ever—especially in Japan—and, to be honest, I'm a little shaken by it.

As I was walking to our local Lawson's to pick up some milk, I saw a young couple standing in front of a building. The man was wearing a suit; the woman a beige sweater and skirt. The woman, who looked to be in her mid 20s, had her right hand placed gently on the man's chest and was talking softly to him. What is she saying, I wondered. With Elbow (the band not the body part) in my ears, I couldn't hear anything, so I pulled the earbuds out as I approached them.

And then, just like that, the woman brought her knee to the guy's groin. He keeled over and she kneed him three more times in the chest. And because the best time you should kick a horse is when it's down and can’t fight back, she started pummeling him with her fists.

I was about 20 feet away from them now and was conflicted. Do I intervene or do I let it pass? In this Age of Believe Women, anyone passing by would probably assume that they guy somehow deserved it. But, having been the recipient of similar violence in the past and almost stabbed I might add, I know that there is often more than one side to the story. Fatal Attraction ring any bells?

As the man crumpled to the ground, the woman turned away and started walking towards me. I was tempted to ask her what happened, to hound her like a paparazzi with question, but held my tongue. We met at the corner of an intersection and finding ourselves in each other's way, we did that awkward do-si-do that you do when you repeatedly step in the way of someone like you've got some kismet thing going on . . . But then, that couple probably thought they had fate on their side, too, when their relationship first began.

A lesson to us all, I thought, as the woman passed and I continued on towards Lawson's: that pitter-patter in one's heart can quickly become a throbbing ache in the groin if you don't play your cards right.

Before I entered the convenience store, I turned and looked back. The young woman was walking with determined steps in one direction; the guy, staggering in the other.

I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of this story. Everyone, include me, has assumed that the guy was somehow at fault. So, what if it was a man clobbering a woman like that?

Of course, the man would be wrong, everyone has told me. A stronger man should never be permitted to attack a weaker woman.

What if it were two men of equal strength?

Well, clearly the man who resorted to violence first would be wrong.

So, why does this chick get a pass? Where is gender equality when it’s a woman raining blows upon a poor defenseless man?

Nah, the guy’s clearly a pantywaist if he can get owned that easily.

Fukuoka Birth Clinic

Every time I hear Americans talk about socialized medicine in other countries, I can't help feeling that they are terribly misinformed. It's a shame really. If only they knew more about the reality of the healthcare systems in Europe and here in Japan, even the most conservative among them might be able to tone down the hyperbole and come to accept that compared to the U.S. people in those other countries have it so much better.

Take childbirth.

For one, it doesn't cost much at all to give birth in Japan. Most if not all of the modest $5000-cost of having a baby (which includes the prenatal care and a five-night stay in the hospital and subsequent check-ups) is covered by subsidies aimed at encouraging Japanese to have babies. In the past, a couple would have been asked to pay the bill upfront upon being discharged and reimbursed later by the state, but today the state pays the hospital directly. Tha was the case with our first child. Our second child didn't cost us a cent out of pocket.

In the U.S. the price of giving birth can vary greatly depending on where and how the baby is delivered--more for c-sections or other complications, of course--and whether or not the mother is insured. Some insurance plans in America do not include childbirth, forcing parents to virtually put their child on consignment. I know one woman, a Filipino-American, who moved to Japan in the final two months of her pregnancy in order to give birth here, because it was the cheaper option. (Obviously, she must be a commie pinko.) Incidentally, even foreigners are able to receive these benefits.

What's more, visits to the pediatrician and medicine for children is covered by the prefecture up to, I believe, junior high school age, which means there is one less thing parents in Japan need to budget for. Whenever our son is sick or hurt, the cost of the treatment or drugs never comes into consideration: we head straight to the pediatrician or hospital.

And the hospital or clinic we go to is entirely our choice.

Many Americans worry that by going the socialized medicine route, they will be giving up the freedom to choose their own doctor, but that couldn't be further from the truth here. In Japan, we go to wherever we like, see whomever we like. Yes, some of the more popular doctors and clinics can be crowded, but if you can’t bear waiting to be treated there are always other options.

We seldom have to wait anyways. My son's pediatric clinic, for example, has an online appointment system. Appointments can be made automatically by email or over the Internet, enabling parents to time their arrival to ten minutes or so prior to having their child seen by the doctor. The same is true with my dentist.

As for the clinics themselves, many of them are modern and clean. Fukuoka Birth Clinic pictured here is a new OB/GYN hospital opened in, I think, 2011 by a friend of mine. We will be having our second child delivered at this clinic.

There is a "roof balcony" on the fourth floor of the hospital allowing mothers to go outside and get some fresh air.

I haven't been to the clinic in some time, so I don't know how the plants have grown or what kinds of flowers are growing in this massive planter.

There are three types of rooms (all single occupancy) for mothers. Women generally spend five nights in the hospital during which time they are taught how to bathe, feed, and change their baby. These long stays is one reason why the infant mortality rate is so low in Japan, second only to Monaco. There are, incidentally, only 2.21 deaths of infants under one year of age per 1,000 live births in Japan, compared to 6.00 in the United States. America is ranked a dismal fifty-first.

Dining room with Arne Jacobsen ant chairs. Nice touch.

Open space allows for lots of sunshine and good circulation of air.

Nurse station

Private room for the expectant mother to relax in while she is experiencing labor pains.

Delivery room.

Waiting area.

Play area for children

Our doctor and friend.

Like a number of my recent posts, this one was moved from an old blog. This one had a number of comments, one of which, I would like to share here:

“You forgot to mention that Japanese nurses don't use any gloves when drawing blood. Also, nurses cough without closing their mouths. Great way to get a newborn ill!!

“If you can't secure a decent job with benefits in the US don't knock it.”

I replied:

Our nurses washed their hands and wore gloves.

As far as the not wearing masks bit, no one on this germ-filled planet of ours wears masks like the Japanese. I am on the train right now as I write this and the man to my left and the man in front of me (2 of the 3 sitting in my area) are wearing surgical masks. Japanese nurses, too, wear masks, especially when they have colds or a bug is going around.

And regarding your rude insinuation that people without good healthcare in the US are somehow undeserving of it, this is pure nonsense. Healthcare should NOT be a privilege for the few, but a right for all.

Japan, with its single-payer universal healthcare, while not perfect, does a remarkable job in providing quality, affordable healthcare. Infant mortality here is one of the lowest--Japan is third after Singapore and Iceland; the US comes in at a dismal 34th with twice as many deaths--and the Japanese have the longest life expectancies (America is 40th). They achieve this spending at less than half what Americans pay. The U.S. spends a whopping 17.6% of GDP on healthcare--the highest--while Japan spends only 8.3-9.5%.

Thank you for your comment, however misinformed it was.

Comment from another reader:

My daughter was born in Japan in 1995 and I believe we were reimbursed soon after delivery. Am glad to hear that changed because it made no sense for the parents to have to pay out of pocket only to get reimbursed. In the States mothers are in and out of the hospital within hours and my wife got to stay 5 days or so in a clinic that looked a lot like the one in the photos.

In 2005 I was diagnosed (in Japan) with a malignant yet indolent cancer and no treatment was needed. I choose to go back to America ... naively thinking health coverage would not be a problem. Both my wife and I have gone long periods without coverage here in the States and may return to Japan simply because the burden is too heavy here: we currently do have coverage but with a $3000 deductible not to mention the out of pocket expenses that are quite high. We can't afford to get sick even with coverage ...

That being said, there has been a healthy benefit to living here in the US: the vitamin and supplement market along with the natural foods industry and health and fitness industry here beats its Japanese counterpart and because of that I am healthier than before. In the European Union, citizens rights to access vitamins and supplements are being withdrawn, which is just what Big Pharma wants.

A “Lottie” had this to say:

I am from the UK and very appreciative of socialised medicine. I think Stephen Hawking made his simple and to the point case for it recently: 'I would not be alive without the NHS'.

I have had to battle a doctor in Japan over birth rights, but I have been fortunate in that I found very good midwives. Both my boys were born in water with soft lights and music - no bright lights, invasive care, stirrups, face masks, and nurses to whisk the baby away after birth. This was my choice in socialised medicine. Perfect. Happy bubs, happy mum, and happy bank account.