I’ve been living in Japan long enough that I know almost all of these political parties.

I can even remember some of the faces behind them, one of whom was Ozawa Ichirō (小沢一郎). Ozawa left the Liberal Democratic Party in the early 93 to form the Japan Renewal Party (新生党, Shinshintō). It was dissolved in December of the following year and merged into the New Frontier Party (新進党, also pronounced Shinshintō, but with a different Chinese character in the middle). The second Shinshintō was created from the merger of like-minded, or rather like-ambitious, politicians from five different parties only to splinter three years later into the New Fraternity Party (新党友愛, Shintōyūai) and Liberal Party (自由党, Jiyūtō). Neither lasted very long and both would, I believe, merge into the Democratic Party of Japan (民主党, Minshutō), which came to power in 1998. Minshutō split into two other, now forgotten parties, plus the Democratic Party (民進党, Minshintō), which finally fizzled in 2018. Many of those former Democratic Party pols jumped ship, joining one of two emerging parties—the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (立憲民主党, Rikken Minshutō), which is now the largest opposition party, and the Democratic Party for the People (国民民主党, Kokumin Minshutō), which is currently in talks with the LDP to form a coalition government.

Phew.

Survival Japanese

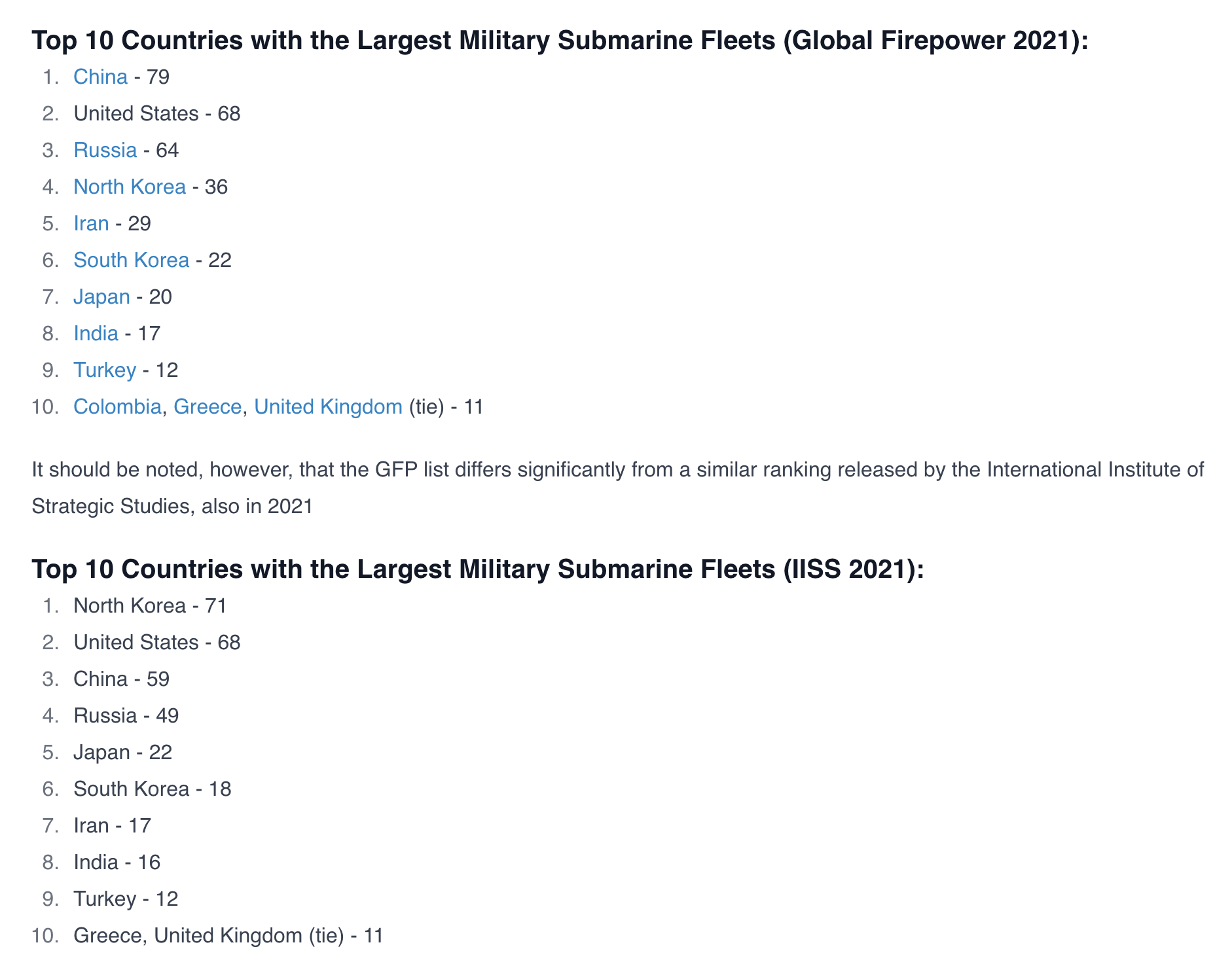

How Many Subs Does Japan have?

Just how many subs does Japan--a country that technically does not maintain military forces--actually possess?

"Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

"In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained."

Oh, never mind about that.

For some perspective, Japan started the Pacific War with 63 ocean-going submarines (i.e., not including midgets), and finished construction on an additional 111 during the war, for a total of 174. Three-quarters of these (128 boats) were lost during the conflict, a proportion of loss similar that experienced by Germany's U-Boats. For more go here.

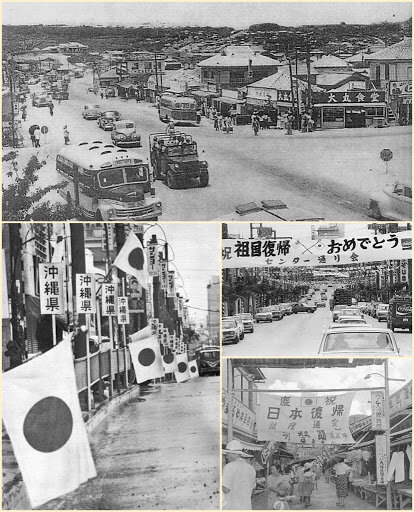

Okinawa Henkan

The US Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands ended on 14 May 1972 when the prefecture was "returned" to Japan the following day. Ryukyuan postage stamps and passports had been in use, and the dollar was the currency until then. Cars continued to drive on the right till 1978.

The return of Okinawa was never a foregone conclusion because the US used the islands as a bargaining chip--first with the Chinese in November of 1943 to keep Chiang Kai-shek from concluding a peace deal with Japan and keep them in the war, then with the Japanese to prevent her from concluding a peace treaty with the USSR. The US warned Japan that if they were to do so, America might keep the Ryukyus under US control forever.

Realpolitik is hard ball.

Before switching to left-hand drive (L) and after the switch in 1978 (R).

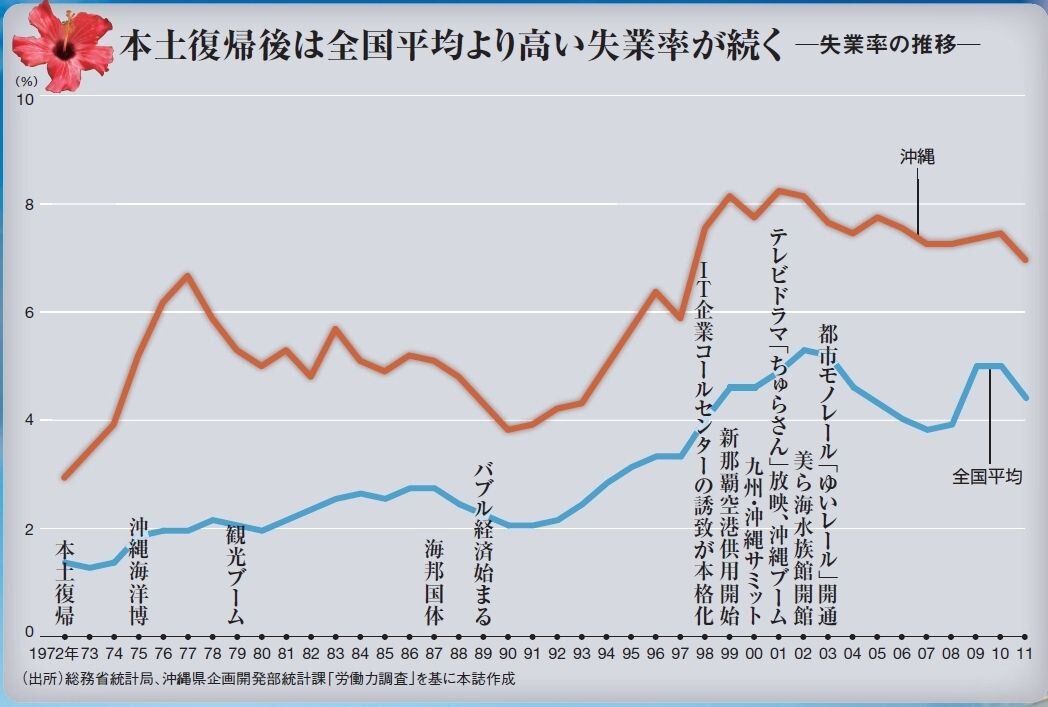

Unemployment rate in Okinawa since its return to Japan in 1972.

Unemployment in Okinawa

Shortly after becoming a prefecture again, unemployment in Okinawa more than doubled from 3% to almost 7%. The average rate in the Japan at the time was 2%. The Amami archipelago also experienced economic hardship when it was "returned" to Kagoshima prefecture in 1953 and was one reason Okinawa was originally cool to the idea of reunification with Naichi (mainland Japan). (I will expand upon this at a later date.)

During the '80s unemployment fell steadily, but rose sharply in the 90s after the asset bubble had burst. Despite a number of public works projects--a new airport in '99 (You should have seen the old one--yikes!), the Yui Rail monorail in Naha in 2003, highway E58 (“goya”) which has been built piecemeal over the past fifty years, the TV drama "Chura-san", which ushered in the "Okinawa Boom", unemployment has remained much higher than the nation's average.

Today, however, things have improved considerably. In December of 2020 unemployment stood at 2.9% nationally and only slightly higher at 3.4% in Okinawa. Among 15~29 year olds, the rate was 5.2% locally, compared to 4.5% nationwide. Mind you, that is during the Covid-19 pandemic which has hit the tourism industry hard.

Red line is Okinawa; blue, national average. R1 is 2019; R2, 2020.

I have been asked why unemployment shot up after the return of the islands to Japan.

I believe a lot of local Okinawans lost jobs they had on the bases. One site says that some 19,000 locals had been employed by the US government, which doesn't sound like a whole lot, but the population of Okinawa was only 970,000 at the time. The labor force at the time was 370,000 people. 20,000 amounts to about 5.5% of the labor force. There were also troop reductions which probably had further knock-on effects to the local economy. Unemployment rose for the whole country at the time, too.

The bases accounted for about 16% of the local economy in 1972. Today that figure is a healthier 5.3%.

Chiyoda Walkabout

One of the things that surprised me when I first wandered about Tōkyō a decade ago was how much open space there was. Walking from Meiji Jingū towards the Imperial Palace I passed several large parks and chanced upon the Akasaka Palace (pictured above and below). Many of the wide boulevards did not have the overhead cobweb of electric cables and telephone wires that Fukuoka had, so you had an unobstructed view of the sky above. How refreshing! I had expected to find a soulless concrete jungle. What I discovered, however, was quite the opposite. I liked it so much that I returned to Tokyo a few months later, then again and again—two, three, even four trips a year—over the next ten years.

This was my first of many walks in the capital.

Akasaka Palace (赤坂離宮, Akasaka rikyu), or the State Guest House (迎賓館, Geihinkan), is one of the two state dues houses of the Government of Japan, the other being the Kyōto State Guest House. The palace was originally built as the Imperial Palace for the Crown Prince (東宮御所, Togu gosho) in 1909. Not too shabby.

In 2012 when I first stubbled upon the palace, it was closed to the public. A few years later, they opened it up. One of these days, I’ll try to get a peak inside.

venue leading from Akasaka Palace towards Hibiya.

Den of Thieves, also known as the headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party, which is neither very liberal or democratic. But they are the only game in town, I’m afraid, after the Democratic Party’s dismal response to the Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011.

This photo was taken in 2012 and boy, what a difference a decade makes. Regardless or your political leaning, you can’t help admitting that the LDP really pushed through a number of reforms that changed life in Japan. Whether those changes were for the better, I’ll leave that up to you. I will say this: where I was once skeptical of Abe’s second stint as PM, near the end I had to say he had been effective, transformational even. If the pandemic never happened, where would we be today?

As is often the case, the Japanese Diet was closed for business when I came a-knockin'. One day I would like to take a tour of the building if that is possible.

The Diet building has been destroyed by Godzilla in the past, but was spared the Allies’ bombs in WWII. There is an interesting interview of Faubion Bowers who was the assistant to the assistant of Douglas MacArthur during the Occupation. He mentions that all the good areas of Tokyo were not bombed because the Americans and Allies intended to use the buildings after the war.

Moat surrounding the Imperial Palace. It was tempting to strip down to my skivvies and jump in.

Western gate leading to the Imperial Palace

The Sakuradamon Gate, location of the Sakuradamon Incident of 1860 when Chief Minister Ii Naosuke was assassinated by rōnin of the Mito and Satsuma Domains after the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the US was signed.

Cherry blossoms at the Cherry Blossom Field Gate (Sakuradamon).

View from Marunouchi Building of the park before the Imperial Palace. This wide open space was also rather unexpected. I really love the Marunouchi area, which I have written about elsewhere.

The 19th century building housing the Ministry of Justice is located across the street from the Imperial Palace.

Rashomon

Thanks to Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 classic film “Rashōmon” (羅生門), which itself was based in part on a short story of the same name by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa†, the name by which most foreigners know the gate differs from the modern name of the gate, Rajōmon, which uses the original kanji (羅城門, where 羅城 rajō refers to the city walls and 門 mon means “gate”). Ra (羅) means a thin, light fabric or netting and 城 (jō, shiro, or sei) means “castle”. Rajōmon was the larger of the two main city gates built in 789 during the Heian Period (794–1185). It measured 32 meters wide by 7.9 meters high and had a 23-meter high stone wall and topped by a ridge-pole. By the 12th century the gate had fallen into disrepair. Today, nothing remains of the fabled gate, except for a stone marker and a bus stop.

† The plot of the movie and characters are actually based upon Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story "In a Grove", with the title and framing story being based on his “Rashōmon”.

Hita, Oita

Hita, a small city located in the western part of Ōita Prefecture, was in olden times a tenryo town. During the Edo Period (1603 to 1868) tenryo towns were under the direct control of the Tokugawa Shogunate and charged with keeping an eye on the happenings of outlying feudal domains. In the case of Hita, it came under the direct control of the House of Toyotomi and oversaw all of Kyūshū.

The neighborhood of Mameda Machi in the center of Hita's old town was a major hub of politics and commerce in Kyūshū during the Edo Period.

Although the area has suffered three major fires over the centuries, many of the houses still look pretty much as the did in the early Edo Period, with their white washed walls and decorative wall paintings, called kotei-e. (Minus all the souvenir shops and busloads of tourists, of course.)

The umé were in bloom throughout the town, filling the air with their sweet fragrance. Even on a day as cold as today was, just seeing these blossoms remind you that spring is around the corner, so hang in there.

At first, I thought the wall of this house had been decorated with stones. On closer inspection, however, I realized that the "stones" were actually clay bricks.

Zōri, anyone?

A shop selling wood and bamboo crafts. I was more impressed with the handwritten signs on each item than I was in the actual merchandise.

I wanted to go inside this building, but my father-in-law was eager to push on.

A close-up of the same building.

The Kunchô Sake Brewery. Built in the Taishō Era (1912–1926), the design incorporates both traditional Japanese building techniques and western influences.

March third is Girls Day in Japan, (every day is Girls' Day in my heart), a day on which parents decorate their homes with traditional Heian Period doll sets (hina ningyō) and plum blossoms and pray for the safety and happiness of their daughters. Superstition has it that your daughter's marriage will be postponed if the dolls continue to be displayed after March fourth, so people usually take the dolls out of storage in February.

Throughout Hita you'll find hina ningyō on display in private homes, restaurants, and shops during the festival.

Kingo Tatsuno

A few years ago, I went on a quest to find the only surviving private home designed by a prolific Meiji Era architect named Kingo Tatsuno (辰野金吾). Built in 1912 for Kenjiro Matsumoto, an industrialist and founder of a private training school for engineers called Meiji Vocational School (today's Kyushu Institute of Technology), the house is currently used by the West Japan Industrial Club (西日本工業倶楽部).

Originally from Karatsu in Saga Prefecture, Kingo Tatsuno studied at the Imperial College of Engineering, becoming one of the first to graduate in 1879 under British architect Josiah Conder. After graduating, Tatsuno went to England where he studied at London University and worked in the office of the Gothic Revivalist William Burges in 1881-2. Before returning to Japan he traveled throughout France and Italy for a year, during which time he was influenced by the Queen Anne style. Upon his return to Japan, Tatsuno taught at the University of Tokyo, and in 1903, started his own architectural firm.

In 1886, Tatsuno was one of the founders of the forerunner of the Architectural Institute of Japan, which was then called "The Building Institute" and based upon the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Kingo Tatsuno's close ties with Shibusawa Eiichi, a Japanese industrialist widely considered the "father of Japanese capitalism", brought him the commission to design the Bank of Japan, which was completed in 1896.

Tatsuno had a strong influence over Japanese colonial architecture - particularly in Manchukuo, where his association with Okada Engineering, the Association of Japanese Architects (日本建築学界), and the new Journal of Manchurian Architecture (満州建築雑誌), helped insure that an architectural style popularized by Tatsuno and called the Tatsuno style (辰野式) became the standard throughout the Japanese colony.

Other buildings of note, include the Bankers' Association Assembly Rooms, Sakamoto-cho, Tokyo (1885), Shibusawa Mansion, Kabutocho, Tokyo (1888), College of Engineering, Tokyo Imperial University, Hongo (1888), the National Sumo Arena, Kuramae, Tokyo (1909), the original school building of Kyushu Institute of Technology (1909), Manseibashi Station (1912), and Tokyo Station (1914).

My first introduction to Kingo Tatsuno's architecture was the former branch office of Japan Mutual Life Insurance Company (日本生命保険相互会社) located in Tenjin, Fukuoka City. Learning that the architect of this beautiful brick building (known as the Fukuoka City Akarenga Cultural Center today) had also designed Tôkyô Station, I became eager to know more about the man and his work.

One thing that I find absolutely flabbergasting is how few Japanese know of Kingo Tatsuno today. While your average America might not be able to name a particular work of Frank Lloyd Wright, I think he would be able to say he'd heard of the architect. Not so with poor Tatsuno. His iconic works remain, but his name does not.

In the coming months, I will travel to the hometown of the architect where a bank he designed still stands.

Comment from a Mr. Andrew C.:

“So interesting. I lived in Fukuoka in the years 1978-79 and 'part of 81. I always liked that red brick building and noiticed it resembled other landmarks of the early 20th century. I missed it the last time I was there in '09 we never went down that street, nice to know it survives! I saw one a really big one of these "Tatsono" structures in Taipei two years ago and know instantly it was a Japanese colonial HQ of some sort.

“I really appreciate that you have noticed the nice neighbohoods around Fukuoka. I spent many hours wondering around btween Yakuin (i lived in a total dump there - long gone). Most of the flat areas have been converted to high rises it seems, in the late 1970s the area around Yakuin was single family a two story apartments. There are nice hill streets along the west side of Yakuin. The zoo area is ful of jewels as well.

I will read the rest of your entries.”

Zakimi Gusuku

Zakimi Castle (座喜味城 Zakimi Gusuku) is a gusuku, or Okinawan fortress, located in Yomitan, Okinawa Prefecture. Built between 1416 and 1422 by the Ryûkyûan militarist Gosamaru, the castle oversaw the northern portion of the Okinawan mainland, then known as the Hokuzan Kingdom. The gusuku fortress has two inner courts, each with an arched gate. This is Okinawa's first stone arch gate featuring the unique keystone masonry of the Ryûkyûs.

During World War II, the castle was used as a gun emplacement by the Japanese army, and after the war it was used as a radar station by the US forces. Some of the walls were destroyed in order to install the radar equipment, but they have since been restored.

Zakimi Castle, along with Shuri Castle and several other related sites in Okinawa, were desiganted a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site in 2000 in time for the G8 summit that was held in the prefecture. They are also designated a National Historical Site.

Itchē naran (いっちぇ〜ならん) Do not enter.

To the Knackers

I had an interesting conversation with a friend a few years ago

For the past several years Kei has been importing riding horses to Japan from Germany and early on I helped her out with correspondence, drawing up preliminary contracts, and so on. The reason she came to me is that, as I have mentioned elsewhere, I once lived in Germany and can still understand the language somewhat. Kei only knew a handful of words: ja, nein, danke schön, bitte. In the kingdom of the blind, they say, the one-eyed man is king.

Fortunately for her and me, most of the Germans we were dealing with spoke damn good English. (That wasn’t the case in the 1980s.)

Two years later, her business has expanded with small, yet encouraging steps and has had her traveling to Europe on a monthly basis, shopping for horses, investing in them, and participating in international equestrian events as a judge. Reading this, you might get the impression that Kei is a fabulously wealthy woman, but nothing could be further from the truth: she is, in fact, a modestly working class, single mother who has gotten by on her wits and creativity. I have a lot of respect for the woman.

Anyways, Kei will be making two trips to Germany again next month to introduce a German breeder/trainer to her Japanese client who’s interested in buying a “high level horse”. Until now, Kei has been buying horses with somewhat humble pedigrees for eventing [1] enthusiasts and riding clubs in Kyūshū and was excited to finally deal in some top level horses.

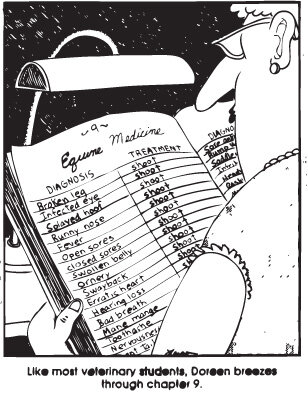

Hearing this, I joked that there were four levels of horses: high-level, mid-level horses, low-level, and glue.

This is where the conversation became interesting.

Kei laughed then told me about a local company called Kohi Chikusan owned by a Mr. Kohi (sounds like the Japanese pronunciation of coffee). Kohi, she said, takes “compromised” horses off of stables’ hands and “makes arrangements for them”. Some of these horses are put down, some are resold and show up, seemingly miraculously, at rival stables, and a few are sold for horsemeat. (Don’t worry, most of the horsemeat used in the delicacy basashi[2] comes from Australia.)

“Whenever a horse acts up or doesn’t respond well,” Kei said laughing, “we tell it we’re going to call Kohi-san.”

I couldn’t help but be reminded of the scene in George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm when Boxer is sent to the glue factory.

I tried to google Kohi Chikusan, but couldn’t find anything.

“They don’t have a website,” Kei said.

“No, I don’t suppose they would.” Talk about a niche business!

Kei explained that they had to use the service because when a horse weighing five hundred kilos dies it’s nearly impossible to move it. Rigor mortis sets in within a few hours after death, freezing the horse in the position that it died in, and the only way to get it out of a stable is to chain it to the back of a tractor and drag it out. Not exactly the kind of thing you want your paying customers to see when they’re practicing their jumps.

“So, whenever a horse becomes too ill for the veterinarian to treat, we call Kohi-san.”

“Kohi isn’t a very common name, is it?” I said.

“That’s because he’s a Buraku-min,” she replied matter-of-factly. “A lot of people involved in that kind of business come from the Buraku-min. Meat handlers, too.”

This morning when I was looking into the family names of the Buraku, I learned that while the caste system of feudal Japan was abolished in Japan in the early years of the Meiji Period and all Japanese were assigned family names, the Buraku-min were given family names that would make them still recognizable from ordinary Japanese a hundred years later. These names apparently include the following Chinese characters: 星 (star); body parts, such as 手 (hand), 足 (foot), 耳 (ear), 頭 (head), 目 (eye); the four points of the compass, 東 (east), 西 (west), 南 (south), 北 (north); 大, 小 (large and small); 松竹梅 (pine, bamboo, plum), 神, 仏 (god and buddha) and so on. Examples include: 星野 (Hoshino), 小松 (Komatsu), 大仏 (Osaragi), 神川 (Kamikawa), 猪口 (Inoguchi/Inokuchi)、熊川 (Kumakawa)、神尾 (Kamio), and so on. (Beware of assuming that everyone with these kinds of names are Buraku-min, they are not.)

I wrote about the Buraku-min in Too Close to the Sun. The passage from my novel discussing these unlucky people has been included below:

In the afternoon, I’m summoned to the interrogation room where Nakata and Ozawa are waiting for me.

Both of them are in an easy, light-hearted mood today. The desk is free of notebook computers; there are no heavy bags filled with thick folders of evidence on the floor.

Ozawa is slouched comfortably in his seat, tanned fingers locked behind his head.

"What was the name of that Korean restaurant you mentioned last week?" he asks.

"Kanō," I say, taking my usual seat, still bolted to the floor.

"Where was that again?"

"It's in Taihaku Machi, a rough neighborhood near the Chidori Bridge."

"Taihaku Machi?"

"Along the Mikasa River, across from Chiyo Machi."

"Chiyo? Ugh!" he says grimacing. "Why is it that all the good Korean restaurants have to be located in the shittiest part of town?"

Nakata asks me if I know what Eta is. I shrug.

Ozawa tries to look it up in his electronic dictionary, but can't find it.

"Figures," he grumbles.

"How do you write it," I ask.

Ozawa scribbles the following two kanji in his notebook: 穢多 The first character, 穢, he says, can be read as kitanai and means filthy. It can also be read as kegare. Finding the entry, Ozawa spins his dictionary around to show me that kegare means impurity, stain, sin, and disgrace. The other, more common character, 多, pronounced ta, or ôi, means plenty, or many. So, eta, connotes something that is abundantly filthy or impure.

Then it hits me that the eta Nakata is alluding to is yet another word that editors of Japanese-English dictionaries conveniently omit: buraku-min (部落民).

Map indicates “Eta Mura” or the area where the outcasts lived.

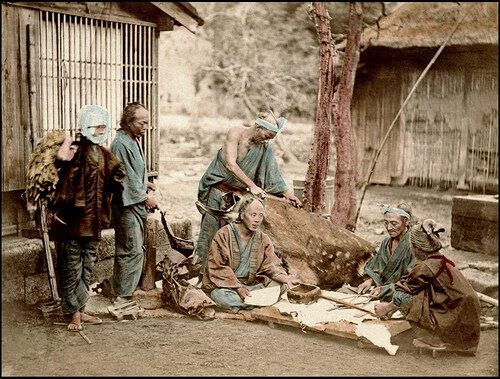

The Buraku-min (lit. hamlet people) were a class of outcasts in feudal Japan who lived in secluded hamlets outside of populated areas where they engaged in occupations considered to be vitiated with death and impurity such as butchering, leather working, grave-digging, tanning and executions.

For the Shintō who believed that cleanliness was truly next to godliness, those who habitually killed animals or committed otherwise heinous acts were considered to be contaminated by the spiritual filth of their acts and thereby evil themselves. As this impurity was believed to be hereditary, Buraku-min were restricted from living outside their designated hamlets (buraku) and not allowed to marry non-Burakumin. In some cases they were even forced to wear special costumes, footwear, and identifying marks.

The Emancipation Edict of 1871 intended to eradicate the institutionalized discrimination and the former outcasts were formally recognized as citizens. However, thanks to family registries, known as koseki, which are assiduously kept by officials in every Japanese city, town and village, it was easy to identify who was Buraku-min from their ancestral home, and discrimination against them continued.

Shortly after coming to Japan, the wife of a company president once confided to me that she and her husband might be willing let his daughter, God forbid, marry an ethnic Korean, but would never countenance her marrying a Buraku-min. He would never hire one, either.

"Never? Regardless of the person's talent?" I asked.

"The damage to the image of my husband's company would be far greater than any benefit such an employee could ever bring."

And that's how it goes in this sophisticated democracy: you can still be discriminated against just because your great-great-great grandfather had a shitty job.

Today there are some four thousand five hundred Dôwa Chiku, or former Buraku communities that were designated by the government in the late sixties for the so-called assimilation projects. Over the next three decades, housing projects and cultural facilities were constructed, and infrastructure improved in the dowa chiku (assimilation zones) to raise the standard of living of the residents of those areas.

There are an estimated two million descendents of Buraku-min in Japan today, most of whom live in the western part of the country, particularly in the Kansai area around Osaka, and in Fukuoka Prefecture.

"Chiyo’s a Dōwa Chiku," Nakata says. "Crawling with Eta."

"I know," I say.

“You do?” They seem surprised.

The fact was first brought to my attention many years ago when I was searching for an apartment. A kindly old woman I had just met was all too eager to help me. She pulled out a map of the city from her handbag and, without elaborating, began crossing out "undesirable places", many of them located along the rivers. When I asked why, she said: "Trust me, you don’t want to live there." And so I did, finding a reasonably priced one-room apartment in one of the tonier areas near Ōhori Park.

"Those people are nothing but trouble," Nakata says. "Riffraff the lot of them."

"You’re kidding, right?"

He leans forward, resting his rotund chest against the desk. "There were a lot of Eta in my hometown when I was young. Nothing, but trouble. If you ever got in a fight with one these Eta bastards, the next thing you know, you're surrounded by a group of them. Sneaky guttersnipes."

The thought of Nakata as a chubby little kid in glasses getting the snot beaten out of him by a gang of Buraku boys almost causes a laugh to percolate out of me.

"Surely not all of them?" I say.

"Yes, all of them," Nakata replies and sits back, brushing his wimpy salt and pepper mustache with his fingers.

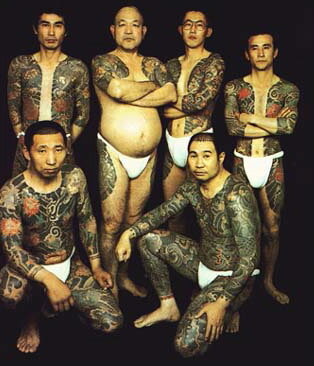

Ozawa asks if I've heard of the Yamaguchi Gumi.

"The yakuza gang?"

"Yeah. Biggest crime syndicate in Japan. It's mostly comprised of these Eta scum."

"Most yakuza gangs are," says Nakata.

"I had no idea," I say.

"Nothing but trouble," Nakata says again.

"Say, what's the deal with the girls working the food stalls at the festivals," I ask. "I've heard they're run by the yakuza."

"They are. The girls are Eta bitches," Nakata replies.

"Pretty damn cute bitches," I say.

Dregs of Japanese society or not, quite a few of the young girls working at festivals are knockouts.

After fifteen years, Japan can still be an enigmatic country. One thing I've never been quite able to figure out is why the best-born Japanese girls are so homely. The ugly daughters of good families, I call them.

"Cute they are," says Ozawa snickering. "Cute they are. Every evening in Chiyo you'll see small armies of the chicks all dolled up hopping into taxis. Off to Nakasū. Shoot the breeze with one of them and some yakuza prick will strut on up and start breakin' your balls as if you were hitting on his woman. That's when the badge comes in handy, of course. Hee-hee."

"I wouldn't go near one of those girls with a barge-pole," Nakata pipes in.

As if the man has to beat the girls away with a stick.

"There's something I've been meaning to ask you," I say.

"Shoot," says 0zawa.

"A lot of the guys in the joint here, and last week at the jail at the Prefectural Police Headquarters, for that matter, are obviously yakuza."

"Yeah?"

"I don't get it."

"Don't get what?"

"In the States, there is, among so many crime syndicates, the Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, right? You know, The Godfather, and all that. Well, these guys used to bend over backwards to deny that the Mafia even existed. Here in Japan, though, the yakuza practically advertise their criminal activity with missing pinkies, lapel pins, and bodies covered in tattoos."

It borders on the absurd. If cops were seriously interested in taking a bite out of crime, the first thing they ought to do is clamp down on these shady characters. The police, of course, will counter that they aren't in the business of preventing crime: they can't make any arrests until a crime had been committed. Which begs the question of why someone like me has to molder away in a stinking cell.

"The ones who strut and swagger," Ozawa says, "are good-for-nothing punks. All bluster and no brawl. They kick up a fuss because they don't have the balls to actually do anything. No, the yakuza you really have to watch out for are the quiet ones, the ones who never raise their voices, or show their tattoos. Those bastards will whack a person at the drop of a hat."

“Better get a hat with a strap then.”

Thank you for reading. This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon. Support a starv . . . well, not quite starving, but definitely peckish: buy one of my books. (They’re cheap!) Read it, review it if you like it (hold your tongue if you don’t), and spread the word. I really appreciate it!

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are (wink, wink) fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Why was Setsubun on February 2nd?

Many people on SNS have noted that Setsubun, the eve of risshun (立春), or the first day of spring according to the lunisolar calendar (tai'in/taiyō reki, 太陰太陰暦), fell on February 2nd for the first time in 124 years. The last time this happened was Meiji 30 or 1897.

But why is this?

Like many “uniquely" Japanese traditions, risshun is actually one of the 24 solar terms of the Asian calendar which originated in China, but spread throughout the East Asian cultural sphere. In China, it is known as Lìchūn and begins when the Sun reaches the “celestial longitude of 315° and ends when it reaches the longitude of 330°. It should be noted that each of the 24 solar terms are spaced 15° apart along the ecliptic, or the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

It takes the Earth 365.2422 days to orbit the Sun and because of that 6 hour difference, the exact time at which the four annual setsubun (yes, four) occurs differs from year to year. Today, we add one extra day to the year every four years, or every leap year. The leap year in Japan is called urūdoshi (閏年). Before the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, each month in Japan lasted 30 days, with the year lasting only 354 days. In order to make up for the loss of 11 days a year, an urūtsuki, or “leap month”, was added every three years.

Incidentally, each solar term is divided into three pentads, or (候, hòu in Chinese; kō in Japanese), meaning there are actually 72 pentads or “micro seasons” in Japan, rather than the exalted four. The present micro season or kō is Harukaze Kōri-wo Toku (東風解凍, also tōfū kaitō) and means “Spring (or Eastern) winds thaw the ice."

The next solar term is Usui (雨水, yǔshuǐ in Chinese, ushii in Ryūkyūan) will fall on February 19th and refers to spring rain.

If you would like to know before hand what day Setsubun will fall on, divide the year by four. From 2021 to 2057, if 1 remains, Setsubun will fall on the 2nd; if two, three, or zero remains, Setsubun will fall on the 3rd. Because of this Setsubun will fall on the second of February every four years from 2021 to 2057.

Date: 1870s

Met's Online Photo Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art released some 400,000 photographic images for non-commercial use in 2014. Among the these are some excellent photos from the late Edo and early Meiji Periods. It's definitely worth perusing.

Olga de Meyer Sitting on the Porch of a Japanese House

Date: 1900s–1910s

Photographer: Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868–1949 Los Angeles, California)

Shrine with Monumental Statue of Buddha

Date: 1890s

Photographer: Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868–1949 Los Angeles, California)

Japanese Woman in Traditional Dress Posing Outdoors

Date: 1870s

Photographer: Shinichi Suzuki (Japanese, 1835–1919)

Date: 1860s–90s

Photographer: Kusakabe Kimbei (Japanese, 1841–1934)

Artists: K Tamamura (Japanese), Raimund von Stillfried (Austrian, 1839–1911), and Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832–1909 Luxor, Egypt)

A Japanese Woman and a Japanese Boy in Traditional Dress

Photographer: Shinichi Suzuki (Japanese, 1835–1919)

Date: 1870s

Street Minstrel

Photographer: Shinichi Suzuki

Date: 1870s

La Toilette

Photographer: Shinichi Suzuki (Japanese, 1835–1919)

Date: 1870s

Mutsuhito, The Emperor Meiji

Photographer: Kyuichi Uchida (Japanese, 1846–1875)

Date: 1872

Tea House waitress

Shinichi Suzuki (Japanese, 1835–1919)

Date: 1870s

Geisha Girls

Photographer: Unknown

Date: ca. 1880

Hikawa Maru

The other day when I was writing about the value of ¥100 in 1946 (see previous post), I remembered visiting the Hikawa Maru which is permanently berthed at Yamashita Park in Yokohama. One of the things that struck me was the cost of a transpacific voyage at the time of the ship’s completion:

“Leaving Kōbe,” a sign on the ship reads, “Hikawa Maru picked up passengers and cargoes at a number of other Japanese ports, and entered the Port of Yokohama. From Yokohama, the ship began the 13-day transpacific trip directly to Seattle. At the time of Hikawa Maru’s completion, the one-way first-class fare from Yokohama to Seattle was about ¥500. In 1930, a new recruit joining NYK Line directly from college would have earned ¥70 a month, and could have buil[t] a house for ¥1,000. Thus, we can see that luxurious first-class travel by sea was special, available to only a handful of privileged individuals.”

The Hikawa Maru had 35 First Class cabins, with a capacity of 76 people. The price, as indicated above, was about five hundred yen, or US$250. There were also 23 “Tourist Class” cabins, accommodating 69 passengers--tickets for the one-way voyage were $125 (about ¥250)--and 25 Third Class cabins that had a capacity of 138. Third Class tickets sold for $55~75 (¥110~140).

Once Upon a Time

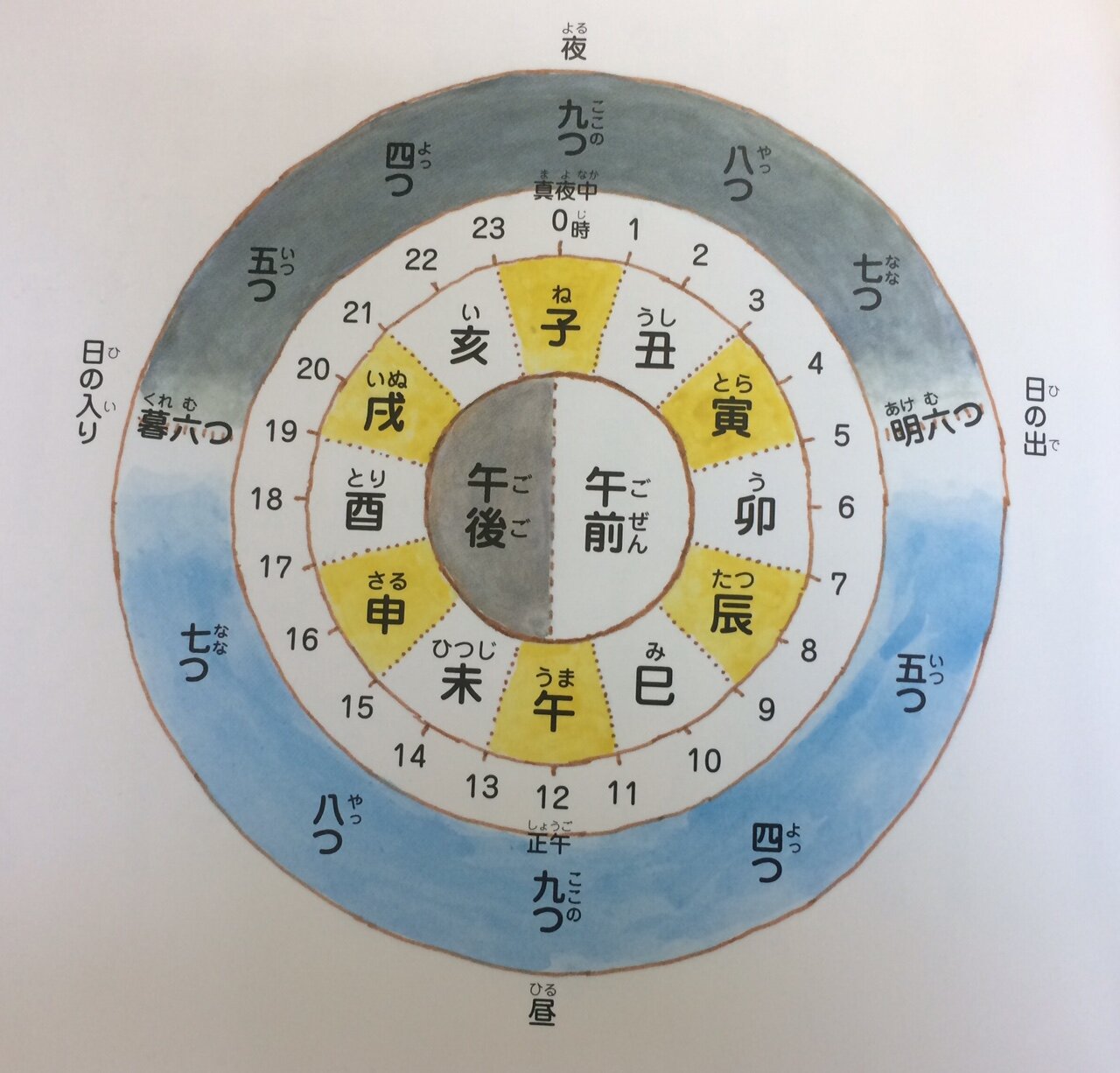

From ancient times in Japan, time was expressed by the duodecimal system introduced from China. The hour from eleven p.m. to one a.m. was known as the Hour of the Rat (子の刻, ne no koku). From one a.m. to three a.m. was The Hour of the Ox (丑の刻の刻, ushi no koku); three a.m. to five in the morning was The Hour of the Tiger (虎の刻, tora no koku); and so on. Today, some people still say ushi mitsu doki (丑三つ時 or 丑満時), meaning in the dead or middle of night.

Later in the Edo Period (1603-1868), a bell was rung to announce the hour, so the hours of the day also came to be known by the number of times the bell was rung. At midnight and noon, the bell was rung nine times. The clock was struck every koku (刻), about once every two hours or so: nine times at noon (九つ, kokonotsu), eight times around two in the afternoon (八つ, yattsu), seven times around four-thirty in the afternoon (七つ, nanatsu), and six times at sunset (暮れ六つ, kuremutsu, lit. “twilight six”). An interesting vestige of this former system, snacks and snack time are still called o-yattsu (お八つ) and o-yattsu no jikan (お八つの時間) today. Around nine in the evening, the bell was rung five times (五つ, itsutsu); at about ten-thirty at night, it was rung four times (四つ, yottsu). And at midnight, the bell was run nine times again. In this way, the bell was rung every two hours or so, first nine times, then eight, seven, six, five, four, and then nine times again.

Another vestige of this the former system is the use of the kanji for “horse” (午) in telling time today. Twelve noon is called shōgo (正午, lit. “exactly horse”) because eleven a.m. to 1 p.m. used to be the Hour of the Horse. Anti meridiem, or a.m., today is gozen (午前, lit. “before the horse”) and post meridiem, or p.m., is gogo (午後, “after the horse”).

Another peculiarity of the former time-telling system was that although night and day was divided into twelve koku or parts, with six always referring to the sunrise and sunset. The length of the koku or “hours” varied throughout the year, such that the daytime koku were longer in the summer months and shorter in the winter months.

I will be adding more to this post in coming days and weeks.

Because one koku was on average two hours long, each koku was divided into quarters, lasting an average of thirty minutes (Ex.: 辰の一刻, tatsu no ikkoku; 丑の三つ, ushi no mitsu) or thirds (Ex.: 寅の上刻, tora no jōkoku; 卯の下刻, u no gekoku). Night and day was also divided into 100 koku. On the spring and autumn equinoxes, day and night were both 50 koku long. On the summer solstice, daytime measured 60 koku and night 40. On the winter solstice, the opposite was true.

One last interesting factoid: each domain kept its own time with noon being the time that the sun was highest in the sky. When trains were first introduced to Japan, it was not unusual for a train to leave a city in the east at say eight in the morning and arrive at a station in another prefecture in the west, say an hour later, but it was still eight in the morning. Trains not only helped industry spread throughout the nation of Japan, but also brought about the first standards in the way time was told.

Kashima Honkan

Back in the 1930s, there were a number of Japanese-style inns located in the vicinity of the former Hakata Station (present day Derai-Machi Park, Hakata Eki-mae), and Taiseikan was one of them. During the Second World War, the inn was used by the Japanese military to accommodate Tokkōtai (特攻隊, lit. “special attack units”) or kamikaze pilots during their final days before departing for Chiran, Kagoshima, the main sortie base from which attacks against Allied ships were launched in the closing days of the war. After the war, the inn was requisitioned by the occupational forces and in 1952 reopened under its present name Kashima Honkan.

Designed in the sukiya manner, Kashima Honkan was designated as a tangible cultural asset in 2007, the first of its kind.

With 27 Japanese style rooms, the inn can accommodate some 18,000 guests annually, a fifth of whom are travelers from abroad.

The Challenge of Repatriating 6.5 Million people

"In the wake of defeat, approximately 6.5 million Japanese were stranded in Asia, Siberia, and the Pacific Ocean area. Roughly 3.5 million of them were soldiers and sailors. The remainder were civilians, including many women and children--a huge and generally forgotten cadre of middle-and-lower-class individuals who had been sent out to help develop the imperium. Some 2.6 million Japanese were in China at war's end, 1.1 million dispersed through Manchuria." (Dower: 1999, pp.48-49.)

I personally know (or rather knew, as many of them have since died) more than ten Japanese who were living abroad at the war's end. Their stories of repatriation are interesting ones.

My father-in-law was born on a ship that was returning to Japan a month before the surrender. I guess his parents had seen the writing on the wall and chose to get out of Dodge before things really turned really ugly. The Battle of Okinawa had finished only a few weeks earlier (June 22) so the waters between Taiwan and Kagoshima (where they were originally from) must have been crowded with Allied battle ships and aircraft carriers getting ready to mount an attack on the Japanese mainland. How their ship was able to pass safely is a mystery to me.

There were some 300,000 Japanese living on Taiwan, 90% of whom were expelled by April of 1946.

Another woman I know grew up in Taiwan. She was the daughter of a police officer on the island. The father of yet another woman was born in a small town on the southeastern coast of Taiwan. His family had been well-to-do, but lost everything when they left.

The father of a woman I know was a doctor in the Japanese Army in Manchuria. 1.6 to 1.7 million Japanese fell into Soviet hands "and it soon became clear that many were being used to help offest the great manpower losses the Soviet Union had experienced in the war as well as through the Stalinist purges." (Dower: 1999, p.52.) As a doctor, he was pretty much free to go were he liked and may have even had one of more Russian lovers during his time there. He remained in the USSR for I believe 8 years after the war. He was one of the few who did not want to be repatriated.

"From a logistical standpoint, the repatriation process was an impressive accomplishment. Between October 1, 1945 and December 31, 1946, over 5.1 million Japanese returned to their homeland on around two hundred Libert Ships and LSTs loaned by the American military, as well as on the battered remnants of their own once-proud fleet." (Dower: 1999, p.54.)

That answers a question I had about how so many people were able to return to Japan when four-fifths of all Japan’s ships had been destroyed. “The imperial navy had long since been demolished. Apart from a few thousand rickety planes held in reserve for suicide attacks, Japan’s air force—not only its aircraft, but its skilled pilot as well—had virtually cased to exist. Its merchant marine lay at the bottom of the ocean.” (Dower: 1999, p.43)

The Akasaka Prince Classic House was built in 1930 as the residence of Yi Un, the last crown prince of Korea. (旧李王家邸).

Tokyo's Chosen Ones

Strategic bombing, the military strategy employed in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale or its economic ability to produce and transport materiel, was used with a vengeance in the Pacific War. Sixty-six major cities in Japan had been bombed, “destroying 40 percent of these urban areas overall and rendering around 30 percent of their populations homeless,” writes John Dower in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Embracing Defeat. “In Tokyo, the largest metropolis, 65 percent of all residences were destroyed . . . The first American contingents to arrive in Japan . . . were invariably impressed, if not shocked, by the mile after mile of urban devastation . . . Russell Brines, the first foreign journalist to enter Tokyo, recorded that ‘everything had been flattened . . . Only thumbs stood up from the flatlands—chimneys of bathhouses, heavy house safes and an occasional stout building with heavy iron shutters.’” (Dower: 1999, pp. 45-46.)

Meiji Gakuin’s Memorial Hall (明治学院記念館) was built in 1890.

Having known of the extensive damage to Tokyo, it always perplexed me that certain buildings like those pictured here managed to remain, ostensibly unscathed by the bombings. Check out a satellite view of Tōkyō on GoogleMap and you’ll find many of these houses hidden like Fabergé Easter eggs in the urban sprawl of the metropolis.

As I was re-reading Dower’s masterpiece on Japan in the wake of WWII, I learned that it was no coincidence that these mansions were spared:

“Even amid such extensive vistas of destruction, however, the conquerors found strange evidence of the selectiveness of their bombing policies. Vast areas of poor people’s residences, small shops, and factories in the capital were gutted, for instance, but a good number of the homes of the wealthy in fashionable neighborhoods survived to house the occupation’s officer corps. Tokyo’s financial district, largely undamaged would soon become “little America,” home to MacArhur’s General Headquarters (GHC). Undamaged also was the building that housed much of the imperial military bureaucracy at war’s end. With a nice sense of irony, the victors subsequently appropriated this for their war crimes trials of top leaders.” (Dower: 1999, pp. 46-47.)

The former residence of Iwasaki Hisaya, an industrialist from the Meiji to Show periods (i.e. Mitsubishi Corporation), was constructed in 1896. It is located in Ikenohatai. (旧岩崎邸庭園)

Former residence of the Maeda family, built in 1929-30. Maeda was the 16th head of the Kaga Domain (present-day Ishikawa and Toyama prefectures). The Maeda rose to prominence as daimyō under the Tokugawa Shogunate and were second only to the Tokugawa Clan in regards to land value.

I have more photos of these buildings and houses which I will upload later.

Tatsuno Kingo’s Works

This painting of 45 of Tatsuno Kingō’s works, including The Bank of Japan (center) and Tōkyō Station (background) gives an idea what the Marunouchi area used to look like before the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, WWII, and the Great Wrecking Ball of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. For more on Marunouchi, go here.

According to Wiki, “Following the Meiji Restoration, Marunouchi came under control of the national government, which erected barracks and parade grounds for the army.

“Those moved in 1890, and Iwasaki Yanosuke, brother of the founder (and later the second leader) of Mitsubishi, purchased the land for 1.5 million yen. As the company developed the land, it came to be known as Mitsubishi-ga-hara (the "Mitsubishi Fields").

“Much of the land remains under the control of Mitsubishi Estate, and the headquarters of many companies in the Mitsubishi Group are in Marunouchi.

“The government of Tokyo constructed its headquarters on the site of the former Kōchi han in 1894. They moved it to the present Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku in 1991, and the new Tokyo International Forum and Toyota Tsuho Corporation now stands on the site. Nearly a quarter of Japan's GDP is generated in this area.

“Tokyo Station opened in 1914, and the Marunouchi Building in 1923. Tokyo Station is reopened on 1 October 2012 after a 5 year refurbishment.”

Amami: What's Behind a Name

My mind has been on Okinawa a lot since returning from there a few weeks ago. If time permits, I'll try to write down some of my thoughts about the trip in the coming days and post some photos, as well.

The other day, I was talking to a doctor. Although he was born near Kagoshima city and has been living in Fukuoka prefecture ever since graduating from medical school, his family originally hailed from Amami Ôshima. He told me that unlike most Japanese whose family names are written with two or three (and occasionally four) Chinese characters (e.g. 田中 - Tanaka, 清水 - Shimizu, 西後 - Saigo, 坂本 - Sakamoto, 長谷川 - Hasegawa, 長曽我部 - Chôsokabe etc.), the family names of the people of Amami Ôshima are often written with a single character (e.g. 堺 - Sakae, 中 - Atari, 元 - Hajime).

This calls for a brief history lesson.

In the late sixteenth century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (warrior and unifier of Japan 1537-1598) asked the Ryūkyū Kingdom for help in his ill-faited attempt to conquer Korea. Hideyoshi intended to take his ambitions on to China in the event that he succeeded in Korea, but as the Ryūkyū Kingdom was a tributary state of the Ming Dynasty, Hideyoshi’s request was turned down.

Having refused demands for aid on a number of occasions, the Ryūkyū Kingdom drew the ire of the newly established Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) and Shimazu clan of southern Kyūshū, and in 1609 the Satsuma feudal domain (present-day Kagoshima prefecture) was given permission to invade the kingdom. While the the Ryûkyû Kingdom was able to regain some autonomy a few years later, Amami Ôshima and other islands north of present-day Okinawa were incorporated into the Satsuma domain. (Incidentally, the islands had been independent before being conquered by the Ryūkyū Kingdom in 1571.) These islands remain part of Kagoshima prefecture to this day although the inhabitants are ethnically, culturally, and linguistically—you name it—closer to Okinawa.

A side note is worth mentioning here: "The islands, by virtue of climmate, were ideal for cane cultivation, and sugar was in high demand in Osaka. To increase revenue, the domain began to reverse its agricultural policy, discouraging the cultivation of rice in favor of sugarcane. In 1746 the domain began collecting all taxes in sugar. In 1777 it established a state monopoly on sugar, making private sales punishable by death. This emphasis on sugarcane led to the most brutal aspect of the island economy: widespread slavery and indentured servitude . . . Cane cultivation was labor-intensive, dangerous, and exhausting, and the most productive farmers were plantation owners who could mobilize scores of unfree workers. By the 1800s the island elite, the district chiefs and local officials, were all slaveholders. By the mid-1800s nearly a third of the populace were yanchu, the island term for chattel slave." (From Ravina, Mark. The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. Hoboken: Wiley, 2004, p.83.)

As was the case for ordinary people in Japan proper, the people of Amami did not have family names until the islands came under the control of the Ryûkyû Kingdom. Family names may have been used in order to keep track of who was entering and leaving the kingdom. During the time that the islands were under the control of the Satsuma han (feudal domain), the residents were classified as farmers under the four occupations social class structure and not permitted to have names. The surnames that survive today were assigned after the fall of the feudal system and Meiji restoration in the late 1860s.

Now there was an exception to certain residents of Amami who had made great contributions to the Satsuma rule. These people, however, were given family names that consisted of one character. One purpose in doing so was to draw a distinction between people from Satsuma and those from the islands. Another reason was that as a tributary of China, the Ryūkyū Kingdom had used Chinese surnames (known as karana, 唐名. lit. “Chinese name”), and assigning such surnames was a way of acknowledging the historical connection to Ryūkyū. (Don’t quote me on this as I’m merely summarizing what others have written in Japanese.)

At the beginning of the Meiji era (1875), all Japanese citizens were required to have family names and the people of Amami tended to choose one-character names that they were familiar with. For a list of these names visit here.

People from outside of Kyūshū often comment that food, especially the soy sauce, is sweeter here than elsewhere. That sweetness is a vestige of those sugar cane plantations.