Learned a new word today: 立志式 (risshi-shiki)

りっししき 【立志式】

【説明的に】a ceremony for fixing one's aim in life.

The Risshiki Ceremony is a ceremony for students to talk about their dreams and goals for the future, and to become aware of their responsibility as adults. It is an opportunity for junior high school students in the middle grades to reconsider their way of life and aspirations.

The origin of the Risshi Ceremony is the “Genpuku Ceremony” (元服) which was once held as a rite for becoming an adult. It is often held at the age of 14, when the mind and body are believed to be undergoing the transition to adulthood, and is positioned as the first step toward adulthood.

At the Risshiki Ceremony, students present their resolutions and dreams for the future. Parents and guardians may also observe the students' presentations.

Survival Japanese

Usui

Usui 雨水 Yǔshuǐ (19 February ~ 5 March)

According to the traditional Chinese calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms (jieqi, 節氣 in traditional Chinese; sekki, 節気, in Japanese), Usui (雨水, Yǔshuǐ in Chinese) is the second mini season of the year. Lasting from roughly February 19th to March 5th, Usui means “rain water”. It is the time when the first day of spring has passed and we begin preparing for the arrival of full-fledged spring. Falling snow becomes rain, and the snow and ice that have accumulated over the past several weeks melt and turn into water.

Kasumi 霞

The phenomenon in which distant objects appear blurry due to water vapor in the air and the faint cloud-like appearance that appears at this time is called kasumi, or “haze”.

Although similar to fog (霧, kiri), it is usually called kasumi in spring rather than kiri, which is the term usually reserved for the mist that occurs in autumn.

春なれや

名もなき山の

薄霞

Harunare ya

Namonaki yama no

Usugasumi

“Spring and the thin haze of a nameless mountain”

This is a haiku by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), the famous haiku poet from the early Edo period. Looking at the thin mist that hangs over the nameless mountain, you can see that spring is in the air.

The ethereal haze hanging over the foothills of mountains and lakes can sometimes appear otherworldly, magical.

Nekoyanagi 猫柳

The Pussy willow is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Salicaceae family, which produces dense silvery-white hairy flower spikes in early spring.The flower spike of the pussy willow resembles a cat's fur, which is—no surprise—how it got its name.

Known as neko yanagi in Japanese (猫柳, lit. “cat willow”), the plant is also called senryu (川柳, lit. “river willow”) because it often grows alongside rivers.

The haiku poet Seishi Yamaguchi (1901-1994) wrote the following poem.

猫柳

高嶺は雪を

あらたにす

Nekoyanagi

Takane wa yuki o

arata ni su

“Takane Nekoyanagi renews the snow”

The silver-white fur of the nearby pussy willow shines, and perhaps the high mountains in the distance are covered in fresh snow and shine brightly. This haiku conveys the signs of spring and the harshness of the cold weather that tightens the body.

Are Kinome and Konome the same?

Although written with the same kanji, 木の芽, konome refers to the buds of trees in general. Read kinome, it refers only to the buds of Japanese pepper (山椒, sanshō).

In recent years, the two are often used interchangeably, but in the past they were used separately.

Is “Doll’s Festival” an event for girls?

March 3rd is the well-known as the Doll's Festival, or Hina Matsuri (ひな祭り). It is also called Joshi no Sekku (女子の節句)

In ancient China, there was a custom to purify oneself in the river on the Day of the Snake in early March. This is known as Jōshi no Sekku, ( 上巳の節句) and is believed to be the root of Hinamatsuri.

It is said that this festival was introduced to Japan during the Nara Period. Over time, Japanese began transferring their impurity to dolls made of paper or straw and then sending them adrift in a river (流し雛).

As time passed, these dolls began to be displayed on doll stands, and the festival evolved into the Doll's Festival.

March in the lunar calendar is also the season when peaches begin to bloom, which is why the other name Momo no Sekku (桃の節句, Peach Festival) was born.

Today, the Doll's Festival is as an event to pray for the healthy growth of girls. Until the Muromachi Period, however, it was a festival to pray for the health and safety of not only girls but also boys and adults.

Translated and abridged from Weather News.

Hempu

Interesting that hemp has long had so many varied uses in Japan except the most obvious one for the leaves and buds.

I found this graphic trying to learn the name of the straw-like material used to wrap up Obon offerings for burning. It was only when I saw the photo that I discovered that some of the items used at Obon are made from the stalk of the hemp plant, or asa.

〖植物, 繊維〗hemp ; 【亜麻】flax ; 【黄麻】jute ; 〖布〗hemp cloth ; 【亜麻の】linen ; 〖糸〗twine.

The rope, asanawa, the chopsticks, asagara-bashi, and asagara, which are used as kindling in the mukaebi fires that greet the souls of the dead, are all made of hemp. The mat in which all the offerings are rolled up and then burned is called makomogoza (真菰ご座) and is made from makomo, or the stalks of the wild water rice plant.

Speaking of Gutters

When learning a language in the country where the language is spoken you may find that you will sometimes be able to not only remember the meaning of a given word but also recall with precise detail when and where the word was first learned or who first uttered it to you in a way that you understood. Because of this, even the most prosaic of words may come to carry far more weight, nuance, and be repositories of memories far richer than those leaned from textbooks.

For instance, I cannot remember when or where I first learned the English word “gutter”, yet I will always associate its Japanese equivalent, mizo (溝) with my first girlfriend in Japan.

It was a hot midsummer’s evening, the rainy season had finally come to an end, and the two of us were making our way towards an old izakaya (pub) in the neighborhood.

As we walked down the narrow, sloping road that led away from my apartment I asked her something that I had been wondering about for weeks: how she had come to get the scar on her forehead. It wasn’t what I would call an ugly or particularly conspicuous scar, certainly not like the one-inch gash leading from my left nostril to my mouth that a dear friend in elementary school christened “The Snot Canal”, but it was there all the same and would stand out in a certain light.

My girlfriend touched the scar and said, “Oh this? When I was about three, I tripped and fell into the, the, . . . the mizo.”

“The what?”

“That,” she said, pointing at the open concrete ditch that lined the road.

“The gutter?”

“The gutter! Yes! I fell into the gutter.”

Why Japan with its otherwise state-of-the-art infrastructure doesn’t cover these driving hazards (And while you’re at it, bury the goddamn telephone wires!) is neither here nor there. What’s interesting to me is that I can recall so vividly where I first learned that and so many, many other words in Japanese.[1]

Incidentally, my three-year-old son recently taught me the word yattsukeru (遣っ付ける). Meaning “to finish off”, as in kill something, to “vanquish”, or “let someone have it”, among other things, Yu-kun said it after he had smashed a bug with a rolled up newspaper. Who taught him the word, I haven’t the slightest clue, but I will never forget when he said it for the first time and the reaction his mother and grandmother had upon hearing him say it with such triumph and élan.

The only trouble I have found with this kind of acquisition of new vocabulary is that the memories surrounding a word are sometimes so rich and detailed that there's sometimes little room for anything else. I can get so caught up wrapping words in memories before packing them away in my head, only to find later that I have misplaced the word altogether.

[1] Another word, or rather phrase, that girlfriend taught me was hayaku.

It was early in the morning and we were getting ready to leave for our long-anticipated trip to the onsen (hot spring) resort of Beppu, Ōita. My girlfriend who was downstairs waiting by her car called up to me, “Aonghas! Aonghas!”

“What?” I called back.

“Hayaku!”

“Haya-what?”

“Hayaku! Hayaku!”

I had no idea what she was trying to tell me. “Hold on a sec,” I said as I popped back into my apartment to fetch my Japanese-English dictionary. “Ha . . . Haya . . . Hayai. Hayaku. Ah, here it is . . . Oh dear.”

She had been telling me to get the lead out, to hurry up.

Weather App

Just noticed a feature on my weather app that describes this morning's weather as:

Currently: Potsu-potsu

9:55: Zaa

10:00: Zaa-zaa

10:05: Para-para

And back to potsu-potsu at 10:10

Okobo

. . . a soft voice called out from behind us: “Sunmahen.”

Turning around, I found a maiko mincing our way.

“Kannindossé,” she said as she passed. [1]

You could barely contain your excitement: “Wasn’t she the most adorable thing you’ve ever seen!”

We watched her walk away in that affected manner of a geisha, then disappear around a corner.

“I’ve never told anyone this, but I wanted to become a maiko myself when I was young.” [2]

“Is that so?”

“No one would have believed it. I was always so boyish as a child, climbing trees, doing karaté . . .”

“Karaté?”

“Yes, I have a green belt.”

“I’ll have to remember to never make you angry.”

“Ha-ha. Anyways, I was always playing dodgeball with the boys in my class. And now that I think about it, I didn’t even wear a skirt until junior high school when I had to because of the uniform. Until then, I was always in pants or shorts . . . Still, in the bottom my heart, I wanted to be dolled up like a maiko, and get fussed over by men. My sister, on the other hand . . .”

“You have a sister?”

“Yes, a younger sister. She’s in college right now. Mana . . .”

“Mana?”

“Yes, Mana. Kana and Mana. We once had a golden retriever called Sana-chan.”

“Funny.”

“Anyways, that sister of mine is the personification of Yamato Nadeshiko.[3] Wide-eyed, skin as white as milk, shy, but coquettish at the same time. She’s shorter than me and slightly plump, but in a good way. At any rate, she’s awfully cute and boys have been throwing themselves at her ever since she was in the fifth grade of elementary school. It’s no use fantasizing . . .”

“Oh, why not?”

“I was always too tall for one.”

“Too tall?”

“They say it all depends on the okiya, but there is a height limit of between one-hundred fifty-five centimeters and one-hundred sixty-five.” [4]

“I didn’t know that.”

“One reason is that the girls share their kimonos so they need to be about the same height. Another reason is that with their hair done up and the okobo sandals they have to wear, a maiko’s height is increased by about fifteen centimeters. I was already one-hundred sixty centimeters tall in junior high school.”

“And with all the get-up, you would have been one hundred and seventy-five centimeters tall. Interesting. I never considered that.”

[1] Sunmahen (すんまへん) is how sumimasen (すみません), or “Excuse me”, is pronounced in Kyōto and neighboring areas. Kannindossé is Kyōto-ben, or Kyōto dialect, for gomen nasai, or “Sorry” or “Pardon me”.

[2] Maiko (舞妓) is an apprentice geiko (芸妓). Traditionally aged 15 to 20, they become full-fledged geiko after learning how to dance, play the shamisen, and speak the Kyōto dialect.

[3] Yamato Nadeshiko (大和撫子) is the personification of an idealized Japanese woman: namely, young, shy, delicate.

[4] Between 5’1” and 5’5”.

The first chapter of A Woman’s Tears can be found here.

注意:この作品は残念がらフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are unfortunately fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon.

Rendez-vous à Kyoto

I stood in front of the Hotel Granvia for about a half an hour, and as I waited for you I couldn’t help wondering what on earth “Granvia” was supposed to mean.

Was it a reference to Madrid’s Gran Via, literally “Great Way”, the so-called “Broadway of Spain”, the street that never sleeps? And if so, what did that have to do with sedate Kyōto, a city where many restaurants close as early as nine in the evening? Or was it in some way an allusion to the “Great Vehicle” of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Probably not. Most likely, the owners just liked the “sound” of it.

These silly, often meaningless names that architects and planners insisted on slapping on buildings, even here in Kyōto, the very heart of Japan, often made me wonder if the Japanese hated their own culture and language.

Unfortunately, the folly wasn’t limited to naming. Infinitely worse, it expressed itself in monstruments like the awful Kyōto Tower that stood across the street from me like a massive cocktail pick. A fitting design, because the people who had the bright idea of creating it must have been drunk.

The bombings of WWII, which reduced most Japanese cities to ashes, spared Kyōto for the most part, meaning the ancient capital is one of the few cities in Japan with a large number of buildings predating the war. Or shall I say, was. Because that which managed to survive the war proved no match for wrecking balls, hydraulic excavators, and bulldozers.

“Stupid! Stupid! Stupid!” I muttered to myself.

“Are you talking about me, Sensei?”

Turning around, I found you and . . . wow.

You were wearing a simple short-sleeved, casual tsumugi kimono with a subdued green and yellow plaid design. The obi, though, was a flash of bright autumn colors—oranges and reds—and all held in place, like the string on a present, with an obijime silk cord olive in color. In your short hair, which had been done up with braids, there was a simple kanzashi ornament.”

“You like?”

“I love!”

“I started taking tea ceremony and kitsuke lessons after moving to Kyōto . . .”[1]

“When in Rome . . .”

“Yes, well. I thought I might as well make the most of my time here.”

“You look gorgeous.”

“Thank you.”

You took my arm and in the Kyōto dialect asked how I was feeling: “Go-kigen ikaga dos’ka?”

“Much better, now.”

“So, where are we going?”

“That depends on you.” I would have loved to take you straight to my hotel room and tear that kimono right off of you, but . . . “What do you want to do? Are you hungry?”

“Actually, I am.”

“Okay, then. What are you hungry for?”

“Anythi . . .”

“Stop it! Now think. What is something you’ve been dying to eat, but haven’t . . .”

“Sushi!”

“In Kyōto? The sashimi at my local supermarket in Hakata is much better than what you’ll find in this landlocked town.”

“True, true,” you said, nodding. “How about tempura, then?”

I didn’t have the heart to tell you I’d just had some, so I directed you towards the taxi stand and said, “I know just the place.” And, off we went.

In the cab, I rattled off directions to an upscale tempura restaurant in the Komatsuchō neighborhood of Higashiyama, halfway between Kiyomizu-dera and Yasaka Shrine. I then called the restaurant to warn them that we would be there.

“Are they still open?” you asked.

“Last order’s in about half an hour. It’ll be a squeaker, but, trust me, it’s worth it.”

“What’s the name?”

“Endō.”

“Endō?”

“Endō.”

“Is it famous?”

“Famous enough, I suppose. I like the old house and the neighborhood that it is in more than food itself, to be honest.”

Before long, the taxi pulled up in front of Tempura Endō Yasaka. I got out first and took your hand to help you out of the backseat. When you stood up, you continued to hold on to my hand, gently, but tight enough as if to say “Don’t let go”, so I didn’t. And warmth radiated from my chest to my extremities, like sinking neck-deep into a bath of hot water, and I almost lost my footing going up the short flight of stone steps leading up to the restaurant.

“Are you okay?” you asked.

“Haven’t felt better in years.”

The proprietress, dressed in a lovely kimono the color of autumn ginkgo leaves and a colorful obi made of Nishijin-ori, stood at the genkan and greeted us in the local dialect, “Okoshiyasu.”[2]

We were led through a narrow hall with earthen walls and exposed cedar posts and beams, to a private Japanese-style room with tatami floors, a low-lying table for two, and a tokonoma alcove in which was hung a scroll with illegible calligraphy on it. Outside the glass doors was a modest garden, no bigger than the room we were sitting in, but ablaze in color because the leaves on the maple trees had already turned.

“How lovely!” you exclaimed as we entered the room.

“I knew you would like it.”

We sat down opposite each other at a table so small our knees touched, but I didn’t mind and I don’t think you did, either.

Shortly after ordering lunch, a tokkuri of good nihonshu at room temperature and two o-choko cups were brought to the table. You took the tokkuri and filled my o-choko with the saké, then you filled your own.

“Kampai!” we chimed and knocked the saké back.

“Ah, I needed that!” you exclaimed.

“Oh?” I said, refilling your cup. “Is it stress?”

“Yes! There’s an older woman at work . . .”

“O-tsuboné?”

You grimaced and took a nip of saké.

The o-tsuboné is a legendary fixture in Japanese offices. These proud, usually single female veterans of the office are capable and efficient, but often harbor a thinly veiled resentment of their younger female coworkers who are fawned over by the men in the office. The term originally referred to women of the Imperial Court or in the inner palace of Edo Castle who were in a position of authority.[3]

“The battle-axe won’t give me a break,” you said, emptying your choko. “Every day it’s something. I waste too much paper when making photo copies. I forgot to turn off the light in the ladies’ room. My slippers are dingy and put customers off when they visit. The tea I made in the morning was too bitter. I didn’t fill out some stupid form the right way . . . Ugh . . . That woman—and I’m starting to suspect that she really isn’t one—didn’t even go to college and she’s bossing me around? I sometimes wonder if the person I came down here to replace didn’t get knocked up just so she could escape from that . . . that bitch.”

I filled your choko with saké.

“And to top it all off, she speaks with the harshest Kansai dialect. Every day it’s Akan this! Akan that! Akan! Akan! Akan![4] I’m sorry. I’ve said far too much.”

“Not at all. Get it all out.”

“I never realized how different the . . . the ‘culture’ could be from one prefecture to the next until I started living here. At first, I thought it was just the dialect. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that the language reflected the mood of a place.”

“Yea?”

“Take ‘Akan’ for example. Conversations here often start off on a negative note. In Hakata, we ask ‘Is it yoka? Is it okay, if I do this or that?” Here, it’s always: ‘If I do this or that, will it be akan? Will it be wrong? Will you get angry?’”

“Interesting. I never thought of it that way. But now that you mention it . . .”

“I really don’t want to talk about it, or that bitch, anymore. So, how’s your work going?”

“Like a dream. I’m busier than ever, but . . . It doesn’t really feel like work.”

“It must be nice.”

“Oh, trust me, I, too, have had my fair share of o-tsuboné, too.”

“At the university?”

“No, no, no. Long before I ever started teaching at the university level.”

“Tell me about it.”

“It’s much too long a story and I wouldn’t want to bore you with lurid tales of jealousy and heartbreak and back-stabbing.”[5]

“Now you have to tell me!”

“Someday, perhaps.”

And then you asked if I had taken my seminar students to the farmhouse.

“No.”

“Oh? Why not?”

“To be quite frank, I knew it wouldn’t be the same without you . . .”

Your tone changed markedly: “Sensei, I hope you haven’t been doing those sorts of things for your own benefit. The students are there to be taught by you, to learn from you, to be inspired by you. They aren’t just there for your entertainment.”

“I know. I know. And I agree with you completely. It’s just that your participation last year, your presence had a way of raising the whole experience to a new level. After you graduated, I knew it would be . . . Let’s just say, yours is a hard act to follow. I knew it would be impossible to fake the enthusiasm, so I decided to take a break. At any rate, this new project, H.I.P. . . .”

And then you burst out laughing.

“Hip!”

Now whenever I say H.I.P. I can’t help but laugh, too, which, I’m afraid, has a way of taking all the urgency and importance of the project.

“But, you’re right. I should be thinking more about the students’ needs and less about mine.”

“Atta boy,” you said, patting my hand.

Just then the waitress arrived with two trays of exquisitely presented food. I held up the empty tokkuri and gestured for another bottle of nihonshu.

Even though I wasn’t all that hungry—I had eaten a tempura teishoku set meal only an hour and a half earlier—the food at Endō was just too good not to dig in: delicately fried garland chrysanthemum, fresh wasabi leaves, slices of satsumaimo sweet potato and yamaimo yam, burdock root, crisp lotus root, and on and on. By the time we were finished I was ready to explode.

As the waitress knelt down besides us and began clearing away the dishes, the proprietress came into the room and asked in her soft Kyōto dialect if we would like some bubuzuke.

“Bubuzuke?” you asked. “What is that?”

“It’s a kind of chazuke.” Bubuzuke, I explained, was a light dish of rice topped with a variety of ingredients such as pickles or small bites of fish, wasabi, and confetti-like seaweed called momi nori sprinkled on top. Over all of this is poured piping hot green tea.

“It sounds wonderful,” you interjected. “I’d love some!”

“No thank you,” I told the hostess firmly. “I’m afraid we haven’t got the time . . .”

Kana, the look you gave me could have killed, so once the hostess and waitress had left the room, I whispered: “I’ll tell you all about it once we’re outside.”

Later, as we walked up Yasaka Dori, the Yasaka no To Pagoda of Hokan-ji rising ahead of us, I explained that in Kyōto asking a guest if he wanted some bubuzuke was the passive-aggressive equivalent of tossing him out the window.[6]

Hearing this, you softened, stepped closer to me, and took my arm.

“How did you get to be so smart?”

“I hope to God that this isn’t smart.”

“No, seriously.”

“Well, by asking questions, for one. By being curious. By wondering why things were the way they were. By reading . . .”

Just before we reached the pagoda, I asked: “You’ve been to Kiyomizu-dera, right?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Then, there’s no reason for us to go there today and deal with the crowds.”

We turned left and headed north down a narrow, cobbled road. Before long, the hordes of tourists posing with their goddamn selfie-sticks thinned out, then disappeared altogether, and we were walking slowly along a quiet street lined with clay walls, old houses and Buddhist temples.

“It’s these subdued pockets, like this neighborhood, not the famous temples and their gaudy souvenir shops and matcha ice cream stands, that are the real charm of Kyōto,” I said. “Unfortunately, the people of Kyōto don’t seem to know it.”

I could have walked all day with you on my arm, but by the time we had reached Chion-in, I could see you were tired. We climbed the stairs leading up to the massive, wooden sanmon gate of the temple and sat down. The city of Kyōto spread out before us, the western mountains—Karasuga-daké, Atago-yama, Taku-san—beyond it.

“Your feet must be killing you,” I said.

“It’s not just my feet.” You gestured at the obi that was tied tightly around your waist. “I want to take this off.”

And I wanted to help you out of it, but judging by the small handbag in your lap, I suspected that you hadn’t brought so much as a change of tabi socks with you.[7]

It was still only three-thirty in the afternoon, but it felt much later, as if evening was fast approaching. Living as long as I had in Hakata, in the southwest of Japan, I took it for granted that the sky remained light well into the evening, but here. The combination of the coordinates and the mountains to the west, meant shadows started to grow much earlier.[8]

“Do you have a curfew?” I asked half-jokingly.

“I do, actually.”

“Really?” I didn’t know whether to be appalled or amused.

“Yes. They’ve got me housed in a company dorm. It’s only temporary, of course, because I might be transferred again in the spring.”

“Is that what you’re hoping for?”

“Yes. No. Oh, I don’t know. I like this town, believe it or not, and want to get to know it better, to explore every part of . . .”

I was dying to explore every part of you.

“. . . but there’s that horrid woman in my office.”

“The o-tsuboné.”

“If it wasn’t for her, I’d be quite happy to live here for a year or two.”

“So, what time’s your curfew?!”

“Ten-thirty.”

“TEN-THIRTY!”

“Silly, isn’t it?”

“I didn’t realize you had to take your Holy Orders when you joined the company.”

“I do sometimes feel like a nun.”[9]

“Unbelievable. Say, Kana, have you been to Shōgun-zuka?”

“I don’t think so.”

“You would know if you had.”

“Where is it?”

I pointed to a flight of stairs behind us: “Five hundred meters up.”

“You don’t expect me to . . .”

“No, no. There is a mountain path that leads up to the top, but, don’t worry, we can hail a taxi and get there in about ten minutes.”

“Let’s go then.”

Part of the Shōrenin temple complex in the eastern mountains of Kyōto, Shōgun-zuka is a two-meter-high mound at the top of the mountain, buried inside of which is a clay statue of a general, or shōgun, adorned with armor, an iron bow and arrow, and swords.[10] Near the mound is the Shōgun-zuka Seiryū-den, a prayer hall, behind which is a broad wooden deck that offers one of the best views of Kyōto and the surrounding mountains.

“I never knew this place existed,” you said, and hurried excitedly to the edge. “It’s lovely.”

“Beats the view from that god-awful Kyōto Tower, doesn’t it? What on earth were they think . . .”

“Oh, I can see my dorm from here!”

“Where?”

“See the station?”

“How could you miss it?” The modern station was almost as insulting to the history and sensibility of the city as that ugly tower.[11]

“See where the train tracks cross the Kamo River there?”

“Yes . . .”

“The next bridge just to south is Kujō. Go west from there and you can see a large apartment building.”

“That’s where you live?”

“No. I live near that. How ‘bout you? Where are you staying?”

“The Monterey,” I answered. And, standing close behind you, I placed my left hand on your obi, and took your right hand in mine. Pointing it to a large rectangle of green in the center of the city, I said: “You know what that is, don’t you?”

“Kyōto Gyoen.”

“That’s right, the Imperial Palace and Gardens. Now follow that line from the southwestern corner of the gardens and continue south past that big thoroughfare, Oiké Dōri, and down about two blocks. Right about . . . there, I think.”

Your cheek rested gently against mine, so I put my hands around your waist, pulled you in tight and listened to you breathe . . . in . . . and . . . out . . . slow . . . and . . . deep . . . in . . . and . . . out.

“Sensei?” you began slowly, in a hushed voice. “I want to go to you to your hotel room, but . . .”

“But, what . . .?”

“But I . . . I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“That stupid curfew, for one. But, more than that, I have to be at work by seven-thirty tomorrow morning.”

“So early?”

“The president of our company will be paying us a visit with some local officials. That’s why I couldn’t get away this morning. We had to get everything in order. We only had one days’ notice. I’m so sorry.”

“Kana, don’t apologize. I didn’t come to Kyōto today with any assumptions. I came here to see you. And I have. And I couldn’t be happier.”

You turned around in my arms and pressed your face into my chest and I thought my heart would explode.

“Will you come to see me again soon?”

“Of course, I will.”

You looked up and gave me the biggest smile. I probably should have kissed you right then and there, but we weren’t alone on that deck. And besides, who, but perhaps an uncommitted cenobite, would want his first kiss to be at a Buddhist temple?

We remained on the deck for several minutes more and watched the sun set over the western mountains.

“If you don’t mind,” you said after a while, “there’s a place I’d like to you to take me.”

“Oh? And where would that be?”

[1] Kitsuke (着付け) lessons teach primarily women the proper way to wear a kimono.

[2] There are two ways to say “Welcome” in the Kyōto dialect: oideyasu (おいでやす) and okoshiyasu (お越しやす). Oideyasu is the more commonly used, and one of the Kyōto phrases most people in Japan are familiar with. Okoshiyasu expresses the feeling that the guests have gone out of their way to come or have come from far away.

[3] Today’s unflattering image of the o-tsuboné (お局) originated from the period drama “Kasuga no Tsuboné” (春日局, Lady Kasuga) which aired on NHK television in 1989.

[4] Akan (あかん) is a widely known saying from the Kansai region (including the prefectures of Ōsaka, Kyōto, Hyōgo, Nara, Wakayama, Shiga, and Mie), which can mean “No!” “Impossible!” “Wrong!” “Hopeless!” “I can’t!” “Incompetent” “You mustn’t do that!” “Stop it!” “Don’t!” “No way!” and so on. Akan is an abbreviation of rachi akanu (埒明かぬ), meaning “to be in disorder” or “to make little or no progress”. A more polite way to say akan is akimahen, but that doesn’t quite convey the irritation, contempt or urgency of “Akan!”

[5] See A Woman’s Nails.

[6] “Kyoto is full of little danger signs which the uninitiated can easily miss. Everyone in Japan has heard the legendary story of bubuzuke (‘tea on rice’). ‘Won’t you stay and have some bubuzuke?’ asks your Kyoto host, and this means that it is time to go. When you become attuned to Kyoto, a comment like this sets off an alarm system. On the surface, you are smiling, but inside your brain, read lights start flashing, horns blare Aaooga, aaooga! And people dash for cover. The old Mother Goddess of Oomoto, Naohi Deguchi, once described how you should accept tea in Kyoto. ‘Do not drink the whole cup,’ she said. ‘After you leave, your hosts will say, ‘They practically drank us out of house and home!’ But, don’t leave it undrunk, either. Then they will say, ‘How unfriendly not to drink our tea!’ Drink just half a cup.’”

From Alex Kerr’s must-read Lost Japan, Lonely Planet Publications, Melbourne, 1996, pp. 173-174.

[7] Tabi (足袋, literally “leg+bag”) are traditional Japanese-style socks with pouches that separate the big toe from the other toes.

[8] On November 28th, the sun rises at 6:30 in the morning in Tōkyō and sets at 4:28 in the afternoon. In Kyōto, it rises at 6:44 and sets at 4:46, but, again, because of those mountains in the west it appears to get darker sooner; and in Fukuoka, the sun rises at 7:02 and sets almost thirty minutes later at 5:11.

[9] Ama-san (尼さん) are what nuns of various faiths, including Catholicism, are called in Japan. Bikuni (比丘尼, bhiksunī) is another name for female monastic members of Buddhist communities.

[10] According to Shōrenin’s website:

“When Emperor Kanmu shifted the capital from Nara to Nagaoka to the south of Kyoto, several accidents occurred continuously. One day, Waké no Kiyomaro invited the Emperor to the mound atop the mountain. Looking down at the Kyōto basin, he suggested to the Emperor to shift his capital here because the land was very suitable for this purpose. The Emperor heeded his advice and began the construction of the capital, Heian Kyō, in 794 AD.

“The Emperor constructed a clay statue of a general, 2.5 meters in height. He adorned the statue with armors [sic], an iron bow and arrow, and swords before he buried it in the mound, as a guardian of the capital. Therefore, the place is known as Shōgunzuka.

“. . . It is believed that . . . political giants stood at this very place and decided to build a wealthy nation, when looking down at the towns of Kyōto.”

[11] Of the modern station, which is almost as insulting to the history and sensibility of the city as that ugly Tower, Alex Kerr wrote: “There could be no greater proof of Kyoto’s hatred for Kyoto.” Kerr, Alex, Lost Japan. Melbourne: Lonely Planet Publications, 1996, p.180.

The first chapter of A Woman’s Tears can be found here.

注意:この作品は残念がらフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are unfortunately fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon.

En Ga Aru

I sometimes tell younger men that if they want to seduce someone, one of the fastest ways to close the deal, so to speak, is to inject a sense of coincidence into their meetings, popping up naturally, nonchalantly where the woman wouldn’t expect to find you. “This can border on stalking,” I warn them, “so be sure not to overdo it.”

After bumping into each other a few times, say to the woman, “It must be fate,” then ask her out for drinks. If she believes that two of you have en (縁がある、en ga aru), why half the work will have been done for you. If, on the other hand, the relationship doesn’t work out, you can say the two of you simply didn’t have en (縁がなかった、en ga nakatta). Couples who divorce or break up never to speak to one another again are said to have cut the en (縁を切った、en-o kitta). Relationships that are difficult to break off are called kusare’en (腐れ縁、lit. a rotten relationship).

When people learn that both my first and second wives hailed from Kagoshima prefecture, one from the Ôsumi peninsula, the other from Satsuma peninsula, they comment that I must have some kind of en with the prefecture. “Yes,” I reply, “in a past life I was Saigô Takamori’s pet dog.”[1]

In spite of my normal skepticism of “destiny”, there are times when the accumulation of coincidence is far too great to ignore. Take the Japanese princesses Masako and Kiko, wives of Crown Prince Naruhito and Prince Fumhito, respectively.

Princess Masako's maiden name was Owada Masako (小和田 雅子, おわだまさこ), Kiko's was Kawashima Kiko (川島紀子, かわしまきこ). Line the two princess's maiden names up side by side with Masako's maiden name on the left and Kiko's on the right and you get:

お o か ka

わ wa わ wa

だ da し shi

ま ma ま ma

さ sa き ki

こ ko こ ko

Now read the boldfaced hiragana.

お o か ka

わ wa わ wa

だ da し shi

ま ma ま ma

さ sa き ki

こ ko こ ko

→ お・わ・だ・ま・さ・こ おわだまさこ 小和田雅子 Owada Masako

お o か ka

わ wa わ wa

だ da し shi

ま ma ま ma

さ sa き ki

こ ko こ ko

→ か・わ・し・ま・き・こ かわしままさこ 川島紀子 Kawashima Kiko

Whaddya think? Have they got en?

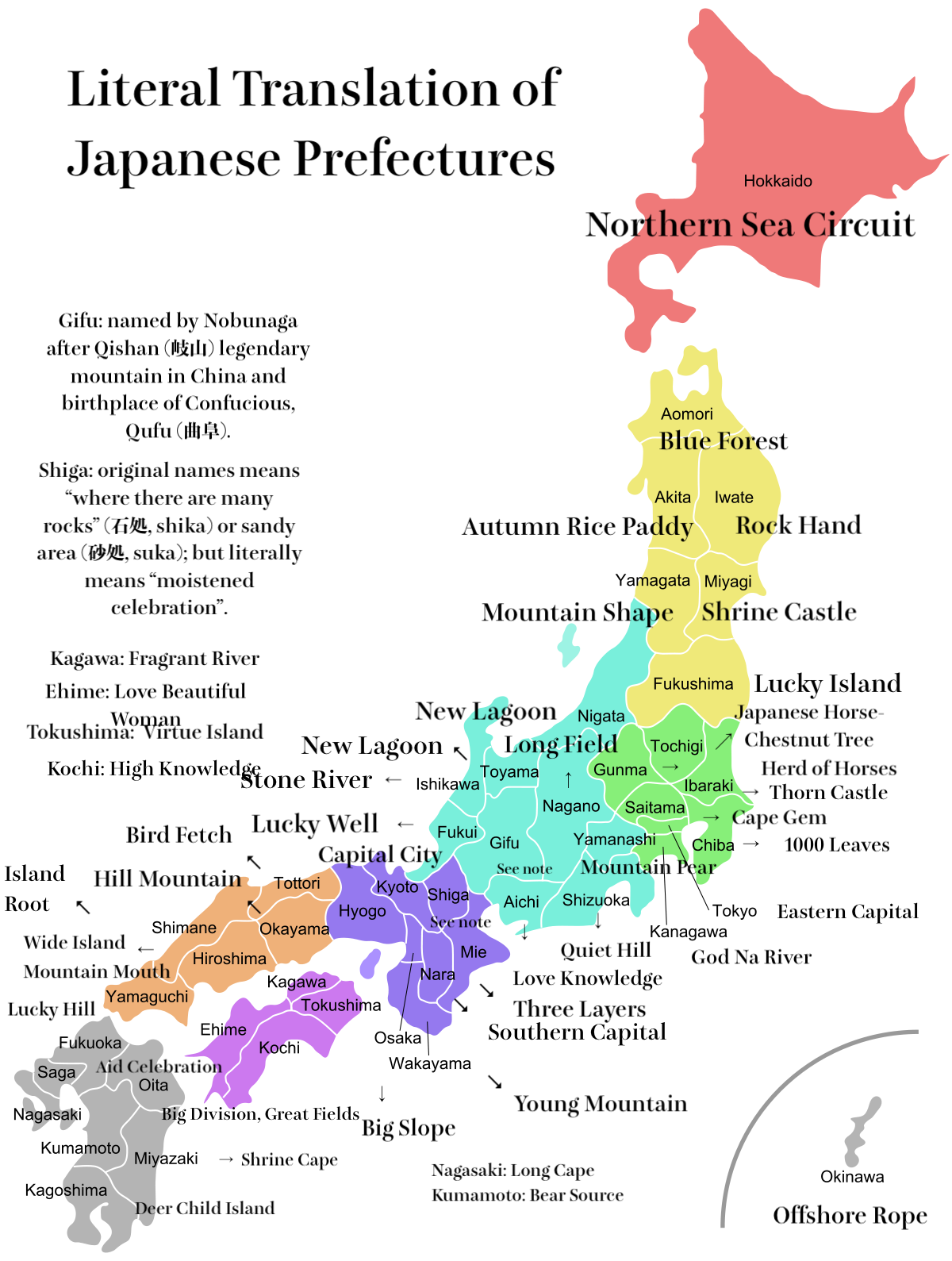

Literal Translation of Japanese Prefectural Names

北海道

Hokkaidō: literally Northern Sea Circuit or Road.

In the Ainu language, it is called アイヌ・モシル, Aynu mosir, which means "Land of the Ainu [people]". Hokkaido was formerly known as Ezo, Yezo, Yeso, or Yesso. Six names for the region were proposed in the Meiji Period, including Kaihokudō (海北道) and Hokkaidō (北加伊道). Hokkaidō written 北海道 was chosen, one, for its similarity to 東海道 (Tōkaidō), and, two, because the Ainu called the region Kai.

青森

Aomori: literally “Blue Forest”

The Japanese word for blue (青) can also mean dark green, so Aomori could be translated as “green forest”. The name Aomori comes from the village of Aomori to which the capital of the newly established prefecture was moved in September of Meiji 4 (1871). The name Aomori had been given to a newly constructed port in the Hirosaki Han (feudal domain) in the early Edo Period (1624). It is said the name originated from the dark green forests that could be seen from the sea.

Ao(i) (青い) is used for a number of things in nature: 青葉 (aoba, “green leaves”, 青りんご (aoringo, “green apple”), 青々とした新緑 (aoao toshita shinryoku, “lush new green leaves”). Green traffic lights (青信号, aoshingō; lit. blue signal) reflected the color found in nature.

秋田

Akita: lit. “Autumn Rice Paddy/Field”

Probably named after the military settlement called “Akita Jō that was built in 733. The fort was the base from which operations to colonize the region and subdue the native Emishi people (lit. “shrimp barbarians”), an ethnic group, possibly distinct from the Ainu and Jōmon, who lived in the Tōhoku region.

岩手

Iwate: lit. “Rock Hand”

Several theories about the origin of the name "Iwate" exist, but the most well known is the tale Oni no Tegata, which is associated with the Mitsuishi or Three Rocks Shrine in Morioka. The rocks are said to have been thrown down into Morioka by an eruption of Mt. Iwate. According to the legend, there once was a devil who tormented the local people. When the people prayed to the spirits of Mitsuishi for protection, the devil was immediately shackled to these rocks and forced to make a promise never to trouble the people again. As a seal of his oath, the devil made a handprint on one of the rocks, thus giving rise to the name Iwate.

山形

Yamagata: lit. “Mountain Shape”

The name comes from the name of a town, Yamagata (山方), meaning near the mountains.

宮城

Miyagi: lit. “Shrine Castle”

The name was taken from the centrally located Miyagi Gun (county or district) when the name changed from Sendai Prefecture in 1872.

新潟

Niigata: lit. “New Lagoon”

Named after the capital of the prefecture. The city itself was named after a place name that was recorded in 1520. The reason for the name, however, was not written, but several theories exist. One, there was a kata or lagoon at the mouth of the Shinano River. Another theory states that in the Shinano River a new island built up naturally over time and was the site of a hamlet called Niigata, but spelt with a different kanji, 新方. And so on.

福島

Fukushima: lit. “Lucky Island”

The prefecture is named after Fukushima-jō, a castle that has undergone a number of name changes over the years. Originally called Daibutsu-jō or Osaragi-jō (大仏城, lit. “Great Buddha Castle”), the Date Clan called it Suginomejō (杉目城 or 杉妻城). In 1592, the area was conquered during the Warring States Period in the late 16th century and became the center of the domain. It was renamed Fukushima as this was considered a more auspicious name.

群馬

Gunma: lit. “Herd [of] Horses”

Originally Kuruma no Kōri, where Kuruma was written with a single character (車, wheel or vehicle). In the early Nara Period (710-794), it became popular to name counties (郡, kōri) or and countries (郷, gō) with two kanji. Gunma, which means “horses herd together”, became the new name. From ancient times, the area had been known as a place where valuable horses roamed.

栃木

Tochigi: lit. “Japanese Horse Chestnut Tree”

Tochigi Prefecture is one of three prefectures, the other two being Yamanashi and Okinawa, in which the capital is located in a city with a name different from the prefecture’s. In the case of Tochigi, the capital is located in Utsunomiya. Tochigi City, however, did serve as the capital city for a spell during the Meiji Period and the prefecture was named after the capital at that time. The name of the city is believed to have come from Japanese horse-chestnut trees that were located in the center of the land that became the city. Another theory is that the name actually means “ten chigi” (十千木, pron. “tōchigi”). Chigi are forked roof finials found in Japanese and Shinto architecture.

茨城

Ibaraki: lit. “Thorn Castle”

There is a lot of confusion as to how to read 茨城. Many people, including myself say “IbaraGI”. The problem was so common, the prefecture conducted an online campaign to teach the correct pronunciation “IbaraKI”, but sometimes you just can’t teach old dogs new tricks. There are three main reasons for the mistake. For starters, that’s how they say the prefectural name in the local dialect, so, um, what’s the problem; two, IbaraGI City in Kansai, which is spelled with the same kanji; and, three, the prefecture MiyaGI which uses the same kanji (城). The name Ibaraki comes from Ibaraki District (茨城郡) in the center of the prefecture. There are two theories regarding the name. One claims that a warrior from the imperial court named Kurosaka no Mikoto destroyed the indigenous tribes wielding thorny branches as weapons. Another theory is that a castle of thorns was built to protect people from bandits. Both stories are similar to other legends that were promoted to establish the authority of the Yamato race as its influence spread throughout Japan.

富山

Toyama: lit. “Wealth/Prosperous Mountain”

The name has its roots in the Muromachi Period (1336~1573) when the area was called 越中国外山郷 (Etchū no Kuni Toyoma-gō), or the “Outer Mountains of Etchū Province”. Toyama spell 富山 was first seen in the Sengoku (Warring States) Period (1467~1615). By the Edo Period (1603~1868), both spellings were being used.

長野

Nagano: lit. “Long Field”

May be a reference to the Nagano Basin of the Chūbu Region. Following the Meiji Restoration, Nagano became the first established modern town in the prefecture on April 1, 1897.

埼玉

Saitama: lit. “Cape Gem”

The name come from Sakitama Mura (埼玉村) in Saitama District, modern-day Gyōda City, and is believed to have originated from the Sakitama Kofun in the city and may have come from the name Sakitama (埼魂), meaning the action of the gods to bring fortune. Another theory states that it comes from Sakitama (前玉 or 佐吉多万) which are mentioned in the Nara Period collection of waka poetry, Manyōshū (万葉集) which was compiled after 759. The pronunciation of Sakitama predates Saitama and reflects a ki→i shift, known as the i-onbin. Examples include:

「埼玉」 サキタマ → サイタマ

「大分」 オオキタ → オオイタ

「次手」 ツギテ → ツイデ 「ついで」

「月立ち」 ツキタチ → ツイタチ 「朔日」

「咲きて」 サキテ → サイテ 「咲いて」

「急ぎて」 イソギテ → イソイデ 「急いで」

「高き」 タカキ → タカイ

「久しき」 ヒサシキ → ヒサシイ

This same shift can be seen in the dialects of western Japan where しないで is often pronounced せんで or せいで: (セズテ → センデ → セイデ). If I am not mistaken, the shift took place in the Heian Period. (Still trying confirm this.)

千葉

Chiba: lit. “One Thousand Leaves”

There are a number of theories regarding the origin of the prefecture’s name. One of them comes from a sakimori no uta (防人歌), a poem in the Manyōshū collection (Vol. 20, 4387), penned by a soldier who was sent to protect the northern coast of Kyūshū. The conditions under which a sakimori traveled and lived were often harsh and their poems reflected this. Ōtabe no Tarihito was one such soldier from the District of Chiba in Shimōsa Province and he penned the following poem:

Original written in man’yōgana:

Original written in man’yōgana:

知波乃奴乃

古乃弖加之波能

保々麻例等

阿夜尓加奈之美

於枳弖他加枳奴

Transliteration:

千葉の野の

児手柏の

ほほまれど

あやに愛しみ

置きて高来ぬ

Romanization:

Chiba no nu no

Konotekashihano

Hohomaredo

Ayanikanashimi

Okitetagakinu

Modern Japanese: 千葉の野の児手柏(このてかしわ)の若葉のように、まだ初々しくて可愛いいあの子を置いてはるばるやってきた。

Interpretation: 千葉の野の、児手柏(このてかしは)の(花のつぼみの)ように、初々しくってかわいいけれど、とてもいとおしいので、何もせずに(遠く)ここまでやってきました。

English Translation: I’ve come from far away, leaving that pure and innocent girl behind like the young leaves of konote oak of the Chiba meadow,

東京

Tōkyō: lit. “Eastern Capital”

Originally a fishing village, named Edo (江戸, lit. “bay/inlet entrance” or “estuary”), the city became the de facto political center of Japan in 1603 as the seat of the Tokugawa Shōgunate. When the shōgunate fell in 1868, the imperial capital of Japan, along with the imperial family, was moved to Edo and the city renamed. The addition of the kanji 京 (kyō) was in line with the East Asian tradition—Beijing (北京, Norther Capital); Nanjing '(南京, Souther Capital), etc.

福井

Fukui: lit. “Lucky Well”

The name of the prefecture was originally written 福居 and refers to the castle that was built on the ruins of Kitanoshō Castle in 1601 by the second son of Tokugawa Ieyasu following his victory in the Battle of Sekigahara the year before. The castle was renamed "Fukui Castle" by the third daimyō of Fukui Domain, Matsudaira Tadamasa, in 1624 after a well called Fukunoi, or "good luck well", the remains of which can still be seen today.

岐阜

Gifu: Wanting to be considered not only the unifier of Japan but also a great mind, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) named the region’s capital Gifu, after Qishan (岐山), a legendary mountain in China and Qufu, the birthplace of Confucius (曲阜).

愛知

Aichi: lit. “Love and Knowledge”

Aichi was the name of the gun (district) which was located where the downtown of modern-day Nagoya City is located and was originally written ayuchi (年魚市) and refers to the Ayuchigata Inlet, mentioned in the Manyōshū collection of classical Japanese poetry of the Nara Period.

「桜田へ鶴(たず)鳴き渡る―潮干にけらし鶴鳴き渡る」

〈万葉集•271〉

意味・・桜田の方へ、あれあのように鶴が群れ鳴き渡って いく。 これで見ると、年魚市潟は潮干したものと 見える。 だから餌を求めて鶴が、あんなに鳴いて 羽ばたいて行くよ。 鶴は干潟に降りて餌を漁(あさ)る習性があるので 年魚市潟の方に飛んで行く鶴を見て潮干になった と想像して詠んだ歌です。

静岡

Shizuoka: lit. “Quiet Hill”.

Named after the Shizuoka Domain that existed in the area from 1869 to 1871 and was centered at Sunpu Castle (駿府城). Prior to that, the feudal domain was called Sunpu-han. The name Shizuoka was decided in 1869 by the political reforms of the hansekihōkan (版籍奉還) royal charter of July 25th of that year. The area around the prefectural office was known as fuchū (府中). Due to the similarity with the synonym fuchū (不忠, lit. “disloyalty”), the Meiji government suggest three other options: Shizuoka (静岡), Shizu (静), Shizujo (静城). The roots of the name “Shizuoka” itself is derived from Shizuhata-yama (賤機山), a 171-meter high mountain in the prefecture. Another word for 賤 (shizu) is iyashii (卑しい) which can mean “greedy”, “vulgar”, “shabby” or “humble”, as in a person of humble birth (卑しい生まれの人).

山梨

Yamanashi: lit. “Mountain Pear”.

From Yamanashi-gun, which was named after a famous ancient pear tear in the mountain behind the Yamanashi Oka Shrine in the Kasugai district (春日居町). There is a tendency to believe that the name derived from the mountain peaches that grew in the area, but according to the Fūdoki (風土記)—ancient reports on provincial culture that were presented to the monarch, and are considered to be the oldest written records from the Nara Period (710-794)—Yamanashi was formally written 山無瀬, 夜萬奈之, and 山平らす (Yamanarasu) in reference to the lack of hills and peaks in the Kōfu Basin (甲府盆地). Over time, Yamanarasu became Yamanashi. In the year Wado (和銅) 6 or 713 AD, the Wadokanrei was passed whereby the names of the provinces had to be written by the most commonly used version in existence at the time. Yamanashi written 山梨 was chosen.

滋賀

Shiga: lit. “Where there are many rocks”.

When the han system was abolished in 1871, eight prefectures were formed in the former Omi Province. A year later, they were unified into Shiga Prefecture. The name "Shiga Prefecture" came from "Shiga District" (滋賀郡) because Otsu, a city on the western coast of Lake Biwa and the capital of the prefecture today, was part of it. As for the origin of the name, there are several theories. The most dominant one claims that it comes from shika (シカ, 石処) which means “place with many stones”. The abundance of other “rocky” areas similarly named Shika have given this theory credence. Another claims that the name comes from suka (スカ, 砂処), meaning wetland or shoal (tidal sandbar).

Finally, there is some conjecture that the name derives from Shika no Shima (志賀島) in Hakata, Fukuoka, which was ruled by the Azumi people (阿曇氏), a seafaring warrior tribe in northern Kyūshū.

三重

Mie: lit. “Three Layers”.

The name Mie is believed to have been taken from the final words of Yamato Takeru (日本武尊 or 倭建命), a semi-legendary prince and son of the 12th Emperor of Japan who died in the Ise Province. As he was traveling from the region of modern-day Kuwana City (桑名市) towards Kameyama City to the south he passed through Mie district, where according to the Kojiki, he said:

Classical Japanese: 吾が足は三重の勾がりの如くして甚だ疲れたり

Transliteration: Wagahai-ga ashi-wa Mie no magari no gotokushite hanahada tsukaretari.

Modern Japanese: 私の足は三重の曲り餅のようになって、とても疲れた。

Translation: My legs were exhausted like twisted Mie magari-mochi.

Notes: まがり餅は米をこねて曲げてあげたお菓子。果たして「まがり」が「まがり餅」だと直結できるのかはよくわかりませんが――まぁ「三重のマガリのごとく」という文章から言うとまがり餅というか「三重のまがり」という造形のお菓子があったという方がすっきりしますね。それだけ「ヘトヘト」という意味でしょう。 ちなみにネットで見ると三重では鉄工業が盛んでその公害で足が曲がった人が実際にいた、という話を見かけましたが、うーん、まぁ、ねぇ。

京都

Kyōto: lit. “Capital City”.

Kyōto was originally called Kyō (京, capital; metropolis), Miyako (都, the capital), or even Kyō no Miyako (京の都) until the 11th century, when the city was renamed "Kyōto" (京都, lit. "capital city"), after the Middle Chinese kiang-tuo (or jīngdū in Mandarin). When the imperial palace moved from Kyōto to Tōkyō in 1868, Kyōto was briefly known as Saikyō (西京), or Western Capital, contrasting it from Tōkyō, the “Western Capital”.

Throughout Eastern Asia in ancient times, the city where the Tenshi (天子) or emperor lived was called Kyō (京) or Keishi (京師), meaning the “capital”. During China’s Jin Dynasty (266-420), however, the character 師 was often used in the “temple names” of emperors, so to avoid confusion—i.e. is this the name of a city or is it someone’s name—都 was adopted.

When Heian-kyō was first being established as the new capital, there was no consensus on how to call it and so the city was called by a number of names: Kyō, Keishi, and Kyōnomiyako.

奈良

Nara: lit. “Flat Land”

A number of different characters have been used to represent the name Nara, including 乃楽, 乃羅, 平, 平城, 名良, 奈良, 奈羅, 常, 那良, 那楽, 那羅, 楢, 諾良, 諾楽, 寧, 寧楽 and 儺羅. The most widely accepted theory for the name of the prefecture (i.e. “Flat Land”) comes from a 1936 study of place names by folklorist Kunio Yanagita (1875-1962) in which he wrote, “"the topographical feature of an area of relatively gentle gradient on the side of a mountain, which is called taira in eastern Japan and hae in the south of Kyushu, is called naru in the Chūgoku region and Shikoku (central Japan). This word gives rise to the verb narasu, adverb narashi, and adjective narushi." Other theories argue that the name is derived from from 楢 nara, meaning "oak”; that it means “to flatten or level (a hill)”; or that it comes from the Korean nara (나라: "country, nation, kingdom").

兵庫

Hyōgo: lit. “Troops Storage”

Named after the castle Hyōgo-jō that belonged to the Amagasaki Domaine and stood at Nakanoshima, Hyōgo Ward from 1581 to 1769. During the Edo Period, it became the seat of the jinya (陣屋) or an administrative headquarters for the province and housed the head of the administration and grain storehouse. Domains assessed at 30,000 koku (4.5 million kilograms) or less of rice had jinya instead of castles. The name itself dates back to Emperor Tenji (天智天皇, 661-672) when there was a tsuwamono (兵) gura (庫), or a place to keep warriors and weapons.

大阪

Ōsaka: lit. “Big Slope”

Wiki: Ōsaka means "large hill" or "large slope". It is unclear when this name gained prominence over Naniwa, but the oldest written evidence for the name dates back to 1496. By the Edo period, 大坂 (Ōsaka) and 大阪 (Ōsaka) were mixed use, and the writer Hamamatsu Utakuni, in his book "Setsuyo Ochiboshu" published in 1808, states that the kanji 坂 was abhorred because it "returns to the earth," and then 阪 was used. The kanji 土 (earth) is also similar to the word 士 (knight), and 反 means against, so 坂 can be read as "samurai rebellion," then 阪 was official name in 1868 after the Meiji Restoration. The older kanji (坂) is still in very limited use, usually onlyin historical contexts. As an abbreviation, the modern kanji 阪 han refers to Osaka City or Osaka Prefecture.

和歌山

Wakayama: lit. “Poem Mountain”

「和歌山(わかやま)」の語源・由来は、「和歌浦」の和歌と「岡山」の山との合成語とされている。住所表記での「和歌浦」は「わかうら」と読むために、地元住民は一帯を指して「わかうら」と呼ぶことが多い。狭義では玉津島と片男波を結ぶ砂嘴と周辺一帯を指すのに対し、広義ではそれらに加え、新和歌浦、雑賀山を隔てた漁業集落の田野、雑賀崎一帯を指す。名称は和歌の浦とも表記する。

『万葉集』にも詠まれた古からの風光明媚なる地で、近世においても天橋立に比肩する景勝地とされた。近現代において東部は著しく地形が変わったため往時の面影は見られないが、2011年にようやく国の名勝に指定され、また自然海岸を残す西部の雑賀崎周辺は瀬戸内海国立公園の特別地域に指定されており、それぞれ保護されている。岡山城(おかやまじょう)は、紀伊国(和歌山県和歌山市岡山丁)にあった日本の城。岡城とも呼ばれる。

沖縄

Okinawa: lit: “offshore rope”

In his Okinawa: The History of an Island People, George H. Kerr writes: “‘a rope in the offing’ . . . is an apt enough description for the long narrow island which dominates our story. On a map the island chain itself suggest a knotted rope tossed carelessly upon the sea. The southernmost island (Yonaguni) lies within sight of Formosa on an exceptionally clear day; the northernmost, severn hundred miles away, lies just off the tip of Kyushu Island in Japan." Between these two points are 140 islands and reefs, but only thirty-six now have permanent habitations on them.” Locally, the name of prefecture is pronounced Uchinaa.

Nodaté

In spite of the fact that I spend a good part of every day with my nose in a Japanese-English dictionary, I seldom come across a completely new word anymore.

I don't mean to imply that my Japanese vocabulary is already so rich or that sentences roll off my tongue like polished jewels. It isn't and they don't. But nowadays whenever I encounter a new word, I find that if I can visualize the kanji that combine to form the word, I can usually guess what the meaning is.

The other day, I was talking with a friend who is a successful restauranteur. He had recently opened up motsu nabe restaurant in Hokkaidō and I was curious to know how he and another friend, who has a chain of yakiniku restaurants in Fukuoka and Tōkyō, could be so consistently successful despite wild fluctuations in the business climate over the past ten years. He answered, "Gūzen-wa hitsuzen." (偶然は必然 (ぐうぜんはひつぜん) literally "Coincidence is inevitable”, but more closer to “Not coincidence, but destiny!”)

He asked me if I knew what hitsuzen meant. I didn't actually, but said I did, because I guessed that the word was written 必然 (ひつぜん), where 必, hitsu orkanarazu, meant "certainly, surely, always", and 然, zen, was a suffix that meant "in that way". I could get the gist of what he was talking about which is usually enough. Not always, but usually.

I sometimes joke that I can understand 90% of the Japanese I read and hear. That may sound impressive until you realize that the remaining 10% is often the most important part of what is being conveyed.

So, it is with nerdish delight when I come across a word that taxes my imagination and yet finds me coming up short of that eureka! of comprehension.

Yesterday, another business man I know, who runs a Doctor Martens boutique and shoe-wholesaling business, told me he had bought a nodatê (野点). I had no idea what he was talking about, so I googled it and found pictures of the large cinnabar-colored paper umbrellas used when the tea ceremony is conducted outdoors. I can't count how many times I've seen them, but never knew what they were called. I would even venture to say that your average Japanese, who hasn't been initiated into the arcana of the Way of Tea, probably doesn't know what they're called, either.

Now I do.

Something else I didn't know yesterday, was the word tateru (点てる、たてる) describes the state in which someone is drinking maccha. It's an unusual reading for the kanji 点 (usually read as ten) and doesn't show up in many dictionaries.

「点てる」は“抹茶をいれる”の意。「お茶を点てる」from my 「スーパー大辞林」

Ebisu Booty

Ask your Japanese friends to try reading 一斗二升五合 and most of them will probably be stumped. It is a riddle of sorts employing 斗, 升, 合, all of which are traditional Japanese measures of volume.

一斗 (itto, about 18 liters) is equal to ten 升 (shô, about 1.8 liters). 一斗, then, can be said to equal 五升の倍 (go shô no bai), which means “five shô doubled”. 五升の倍 (go shô no bai) is synonymous with 御商売 (go shôbai) which means “one’s business or trade”.

Still with me?

二升 (nishô). 升 can also be read masu. 二升 here can be read “masu masu” which sounds like 益々 (masu masu), meaning “more and more”, “steadily”, and son on.

五合 (go gô, 5 x 0.18 liters, or 0.9 liters) is one half of a shô or 半升 (hanjô) and sounds the same as 繁盛 (hanjô, prosperity).

So, putting it all together 一斗二升五合 can be read “Go-shôbai masu masu hanjô!” (御商売益々繁盛), meaning something to the effect that your business or trade will enjoy increasing prosperity.

Japanese is Difikaruto

One thing that comes up time and time again when people who are unfamiliar with Japan read my writing is the issue of why the Japanese language uses "Chinese characters". "What?" they invariably comment. "I thought this was supposed to be Japanese . . . Is this Japanese or is this Chinese? I don't get it." Don't worry. I asked the same question almost thirty years ago. (For more on the Japanese writing system, scroll down to the bottom.)

Every day I hear Japanese complain, “Eigo-wa muzukashii.” (English is difficult.)

I suppose for non-native speakers of the language, English can be hard to master. This blessed tongue of mine is a hodgepodge of languages—Germanic, Romance, Celtic, etc.—making the spelling and grammar a confused mess that is not only cumbersome for learners but for native speakers alike.

BUT! The Japanese language is so much more muzukashii. Our list of irregular verbs and odd spelling rules cannot even begin to burden a student the way the Japanese writing system hinders foreigners who try to master it.

Of the more than five thousand different languages out there in the world, the most difficult one to read has got to be Japanese.

It’s not unusual to find a single sentence chockablock with Hiragana (ひらがな), Katakana (カタカナ), Kanji (漢字), Rōmaji (also known as the alphabet), and even Arabic numerals. While hiragana, katana, and rōmaji are straight-forward enough and can be mastered in less than a week, what really makes Japanese so hellish for learners (especially non-East Asian ones) is the fact that unlike the pictograms in Chinese, known as hànzi (漢字), where most characters have one basic reading, almost all Japanese kanji have several possible, often unrelated readings.

Take the kanji for “I”. In Chinese 我 is pronounced wǒ. In Japanese, however, it can be pronounced: a, aré, ga,wa, waré, and waro. The character for “food/eat” 食 is read shí in Chinese, but can be read: uka, uke, ke, shi,jiki, shoku, ku, kui, su, ta, ha and so on, depending on context. And while the kanji for “go”, 行 can be read in a number of similar ways in Chinese—xíng, háng, hang, héng—in Japanese it can be read in the following ways: kô, gyô, okona, yu, yuki, yuku, i, an, and, who knows, possibly more.

Kids in Japan must master 1,006 of the 2,136 different characters, the so-called jôyô kanji,[1] by the end of elementary school and the remainder in junior high school.

Think about that.

It can take up to nine years of education for a Japanese child to become literate in his own language, far longer than it takes an American to learn how to read English. By comparison, hangul (한글) the Korean writing system can be mastered for the most part in a single day. If you’re determined enough, that is. I taught myself how to read (though not quite understand) hangul during a trip I took in the mid 90s. Riding on the high-speed train connecting Busan in the south of the country to Seoul in the north, I compared the Romanization of the station names and the Chinese characters with the hangul. By the time I reached Seoul a few hours later, I could read the Korean script. Piece of cake!

No other language offers as overwhelming a barrier to entry as Japanese does when it comes to its writing system. As a result, students of the language are often forced to focus on speaking alone. They cannot reinforce what they learn by, say, reading books or magazine and newspaper articles the way you can with other languages.

If they ever try to do so, however, as I did, they’ll find that written Japanese is a very different animal from the spoken language.

Open up any book, even a collection of casual, humorous essays by Murakami Haruki for example, and you’ll immediately bump up against “ーde-aru” (ーである). I hadn’t heard of this copula[2] until I started trying to read things other than textbooks and manga.

De-aru, which is just another way of say desu (ーです) but in a more formal and rigid way that is suitable for reports or making conclusions, is only the beginning. While I can generally catch almost everything that is being said to me or what is said on TV even when I’m not really paying attention,[3] written Japanese takes concentrated effort to comprehend and sometimes up to three perusals[4] to get a firm grasp on what the writer is trying to convey.

Even if you’re not interested in learning how to read Japanese, just trying to master the spoken language can provide you with years of headaches.

Thinking I could master the language in my first three months or so in Japan—Hah!—I dove headfirst into my studies almost as soon as I arrived, taking sometimes two to three private lessons a week.

At the time, the selection of textbooks for learners of Japanese was extremely limited. While I had a good set of dictionaries called the Takahashi Romanized “Pocket” Dictionary—the only kind of pockets they would conceivably fit in were the pockets you might find on the baggy pants of a circus clown—the textbook I had to work with couldn’t have been more irrelevant.

Written for engineers from developing countries invited by the government to study and train in Japan, it contained such everyday vocabulary as “welding flux”, “hydraulic jack” and “water-pressure gauge”. The phrases taught in the textbook were equally “helpful”:

Q: ラオさんは何を持っていますか。

Rao-san-wa nani-o motteimasuka

What is Rao-san holding.

A: ラオさんはスパナを持っています。

Rao-san-wa supana-o motteimasu

Rao-san is holding a spanner.

In all of my twenty years in Japan, I have never once used this phrase. I haven’t used a spanner or a wrench for that matter, either. Nor have I met anyone named Rao-san.[5]

But, the biggest shortcoming of the textbook was its desire to have learners of Japanese speak the language politely.

And so, the less casual -masu (−ます) and -desu (—です) form of verbs triumphed. If you wanted to ask someone what he was doing, the textbook taught you to say:

あなたは、なにをしていますか?

(Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka?)

I practiced this phrase over and over: Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka? Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka? Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka? Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka? Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka?

Armed with this new phrase, I went up to a group of children in a playground and asked, “Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka?”

Crickets.

A few months later I was diligently studying Japanese in that most effective of classrooms—a girlfriend’s bed—when I learned that people didn’t really say Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka, especially to children much younger than themselves. No, they said, “Nani, shiteru no?” or something like that, instead.

After about a year of studying the language, I could manage. I certainly wasn’t what I would call fluent, but I was no longer threatened by death or starvation. When I moved to Fukuoka, however, I bumped up against a new and very unexpected wall: hôgen. The local patois, known as Hakata-ben, is one of the more well-known of Japan’s many bens, or dialects.

When the people of Fukuoka wanted to know what you were doing, they didn’t say anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka or even nani, shiteru no. They said, “Nan shiyô to?” (なんしようと) or “Nan shon?” (なんしょん).

Let me tell you, it took quite a few years to graduate from saying “Anata-wa, nani-o shiteimasuka?” to “Nan shiyô to?” And that, of course, was only the beginning. It took me nearly a decade to figure out what 〜んめえ (~nmê) and ばってん (batten) meant.

Example:

博多弁: 雨なら、行かんめーと思うとるっちゃばってん、こん様子なら降らんめーや。

Hakata-ben: Ame-nara, ikanmê to omôtoruccha batten, kon yôsu nara, furanmê ya.

標準語: 雨なら行くまいと思ってるのだが、この様子だと雨は降らないだろう。

Standard: Ame nara, ikumai to omotteru-no daga, kono yôsu dato, ame wa furanai darô.

English: I was thinking of not going if it rained[6], but it doesn’t look like it’s going to rain (after all).

My Japanese grandmother would say something like, “Anta, ikanmê” (you aren’t going, are you) to which I’d grunt, “Un” (that’s right), when in fact I had every intention of going. The poor woman and I had conversations like that all the time.[7] When I finally figured that one out it was as if the scales had fallen from my eyes. Day-to-day life here has contained fewer misunderstandings ever since. ばってん (batten), by the way, means “but”.

My experience with Hakata-ben has spawned a masochistic interest in Japanese dialects in general and I have been maintaining a blog on the topic for the past few years. Have a look-see!

Anyways, the long and short of it is that while English is no cakewalk, it’s still much easier to learn than many other languages, such as Japanese. So, the next time you hear your students grumbling about how difficult English is, just tell them, “Oh, shuddup” or in Hakata-ben: “Shekarashika-ken, damarī”.

So, why "Chinese characters"?

Mr. Wiki says: "The Japanese language had no written form at the time Chinese characters were introduced, and texts were written and read only in Chinese. Later, during the Heian period however, a system known as kanbun emerged, which involved using Chinese text with diacritical marks to allow Japanese speakers to restructure and read Chinese sentences, by changing word order and adding particles and verb endings, in accordance with the rules of Japanese grammar."

[1] 常用漢字, jōyō kanji, are the Chinese characters designated by the Ministry of Education for use in everyday life.

[2] A copula is a word used to link a subject and predicate, as in “John is a teacher”, where “John” is the subject, “a teacher” (actually a predicative nominal), the predicate and “is”, the copula. (Don’t worry; before I started studying Japanese, I thought copula was a film director.)

[3] Unless it’s a period piece and the actors are using Edo Period Japanese.

[4] I use the word “perusal” to imply thoroughness and care in reading. So many Americans today mistakenly assume the word means “to skim”. It does not, it does not, it does not. So, for the love of God, stop it! Same goes for the word “nonplussed”. If you’re not a hundred percent certain of the meaning—and even if you are (over confidence is America’s Achilles heel)—don’t use it. Chances are you’re probably mistaken.

[5] I eagerly await his arrival, though. For when I find him, I will surely ask, “ラオさん、何を持っていますか?”

[6] I have intentionally translated this in the manner that Japanese speak—namely “I was thinking about not doing” rather than the more natural “I wasn’t thinking about doing”—to make the original sentences easier to understand.

[7] Incidentally, while in Tōkyō I chatted up a girl from Gifu who told me that they also used the same ~nmē verb ending. Her friend from Hokkaidô had never heard it before.

P. K.

I asked a group of young women if they could throw some common—and not so common—Japanese abbreviations at me.

Old standards, of course, are OL (Office Lady), OB (Old Boy, as in an alumni network), and TPO (Time Place Occasion).† Ones I hear rather frequently now include CA (Cabinet Attendant, i.e. stewardess, who for the longest time were called “sutchi”) and KY (Kuki-o Yomenai, which refers to someone who can't read the mood of a situation; i.e. someone who just doesn't get it.)

Newer abbreviations, though, can be rather funny.

“PK,” one of the girls in the back of the classroom called out to peals of laughter.

"PK?" I asked. "PK, as in penalty kick?"

The girl giggled and said, "Yes, sensei, penalty kick."

I could tell that she wasn't telling me the truth. "C'mon, what does it really mean?"

"It's embarrassing."

"Yes, but, you brought it up."

"パンツ食い込み (pantsu kuikomi)."

"Aa-ah," I said, as the image hit me. (Don't recommend googling that when you're at work, by the way.)

And then the girls rolled about in the aisles between their desks, as they do.

PK is no laughing matter. According to a highly scientific study conducted by Wacoal, a manufacturer of lingerie, some 80 percent of Japanese junior and senior high school girls, namely JC and JK, are troubled by PK. Fortunately, the good people at Wacoal have come to the aid of these fair damsels in distress with a new line of inexpensive skivvies called NPK, or “Non-P. K.” that retail for ¥1,100. SM no more! Shimpai muyō (心配無用).

More abbreviations include:

HK 話、変わるけど(Hanasi Kawarukedo)

HM 話し戻る けど(Hanasi Modorukedo)」

MK5 マジ(Maji))で切れる(Kireru)5秒前

WK しらける from 白+蹴る=White+Kick

AY 頭(Atama)」+「弱い(Yowai)

AKY あえて空気読まない which is further abbreviated to KY

MMK モテて、モテて、困る (異性から人気があり過ぎたり、多数の異性から言い寄られて困るという場合に使用する)

For more of these abbreviations, go here.

Most Japanese believe that TPO is English, but it was actually thought up by Ishizu Kensuke (石津 謙介), the founder of Van Jacket, an apparel maker popular between the 60s and 80s.

Fukyo Kunshu

On my way home from this morning’s run, I found the following post at the entrance to a temple:

不許軍酒入門内

Reading: fukyo kunshu nyūmonnai

Meaning: くさいにおいのする野菜と、酒は、修行の妨げになるので、寺の中に持ち込んではならない、ということ

軍 (kun) refers to not only vegetables such as garlic, leeks, and onions, but also “nama-gusai” (foul-smelling or fishy) meat and seafood.

These things as well as alcohol are proscribed as they interfere with the religious training of the monks in the temple.

Another variant is:

不許軍酒入山門

山門 (sanmon) means the main entrance to a temple, the temple itself, or a Zen temple. In the past, temples were located in the mountains (山) far from human habitation (人里離れた).

重要語の意味

葷=「くん」と読み、①くさみのある野菜、にんにく、にら。②生臭い肉と魚。 酒=アルコールを含む飲み物で、アルコールによって人の脳をまひさせるもの。 日本酒、焼酎(しょうちゅう)、紹興酒(しょうこうしゅ)など。 山門=「さんもん」と読み、①寺の正面の門。②お寺。禅寺。(お寺は本来、人里離れた山にあるべきなのでこのように言う)。 入る=「いる」と読み、はいるの古い言い方。 許さず=「ゆるさず」と読み、許さない。そのようにさせない。 修行=「しゅぎょう」と読み、仏教を学びその真理にもとづく悟りを得るために努力すること。 妨げ=「さまたげ」と読み、物事が進むのにじゃまになる。 寺=「てら」と読み、仏像を置いて僧侶が住み仏教の修行をするための建物。 戒律=「かいりつ」と読み、寺の僧侶が守るべき日常のきまりごと。不殺生、不偸盗、不邪淫、不妄語、不飲酒など。 戒壇石=「かいだんせき」と読み、戒律を守る目的で設けられた小さな結界を示す目じるしの石。結界石。 出家=「しゅっけ」と読み、一般の人が住んでいるこの世間を捨て仏門にはいること。 結界=「けっかい」と読み、寺の秩序を守るために決める一定の限られた場所。修行の妨げとなるものが入ることを許さない場所。

For more on this, go here.

P.K.

I asked a group of college women to give me some examples of common and not so common Japanese abbreviations.

Old standards, of course, include OL (Office Lady), OB (Old Boy, as in an alumni network), and TPO (Time Place Occasion).

Recently popular ones are CA (Cabinet Attendant, i.e. stewardess) and KY (Kuki-o yomenai, referring to someone who can't read the mood of a situation; i.e. someone who just doesn't get it.) Not sure when flight attendants started being called CAs here. For the longest time they were called stewardesses, or "succhi" for short, but never F.A. Maybe because there is an “l” in “flight”.

The newer abbreviations the students offered up were rather funny, my favorite among them being PK.

"PK?" I asked. "PK, as in penalty kick?"

The girl laughed and said, "Yes, penalty kick." I could tell though that she wasn't telling me the truth.

"C'mon, what does it really mean?"

"It's embarrassing."

"Yes, but, you brought it up."

"パンツ食い込み. (Pants kuikomi)"

"A~h so~~~."

I don't recommend googling that when you're at work.

Doyo no Ushi

On Tuesday, you will probably be seeing 土用の丑 (doyō no ushi) on signs at your local supermarket or izakaya. What the hell is this?

Doyō (土用) refers to the 18 days before the change of a season (節分). In the case of 7/21, it refers to the 18 days before the start of autumn or rishhū (立秋), lìqiū in Chinese. This year rishhū is on August 7th.

The beginning of this 18-day period is known as 土用の入り (doyō no iri); the final day, 節分 (setsubun). Yes, there is more than one "setsubun" in Japan—four actually—not just the one in February when people play exorcist and throw beans at demons.

As it is believed that one becomes susceptible to all kinds of ailments when seasons change, the Japanese like to fortify themselves with unagi (grilled eel, pictured), udon, and umeboshi (pickled plums). Why these things? Because they start with "u", just like the "u" in "doyō no Ushi". Yes, that is the reason. Silly, ain' it?

The "do" in "doyō" incidentally means earth/soil, and is one of the five ancient elements, 五行 (Gogyō, or wǔxíng in Chinese). These five elements (fire, water, wood, metal/gold, earth) are also the same as the days in the week. Most people believe these came from China, but they actually came from the Roman Empire, which created the 7-day week and gave us the names for the days which today are still reflected in the Japanese--namely, Nichiyōbi (Sun Day), Getsuyōbi (Moon Day), Kayōbi (Mars/FIre Day), Suiyōbi (Mercury/Water Day), Mokuyōbi (Jupiter/Wood Day), Kinyōbi (Venus/Metal Day) and Doyōbi (Saturn/Earth Day). The order of the days, I believe, was connected to the speed at which they passed through the sky. (I need to double check that.) Interestingly, in Chinese, they just call the days "the first day of the week, the second day of the week", which is kind of what you would expect of a humorless and Godless, Communist dictatorship.

The "ushi" in dōyo no ushi means cow. (As you may know, there are 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac. 12 animals x 5 elements gives us 60 different combinations.)

And so what "dōyo no ushi" actually means is this: "the day of the cow that falls within in the 18 days before the start of a new season according to the ancient luni-solar calendar."

Got that?

But wait! If there are only 12 elements and 18 days of the doyō period, then there must be two doyō no ushi days. Yes, you're right. At least in most years you are. This year, there will be two doyō no ushi. The first (一の丑, ichi no ushi) falls on July 21st; the second (二の丑, ni no ushi), on August 2nd.

Bon appétit!

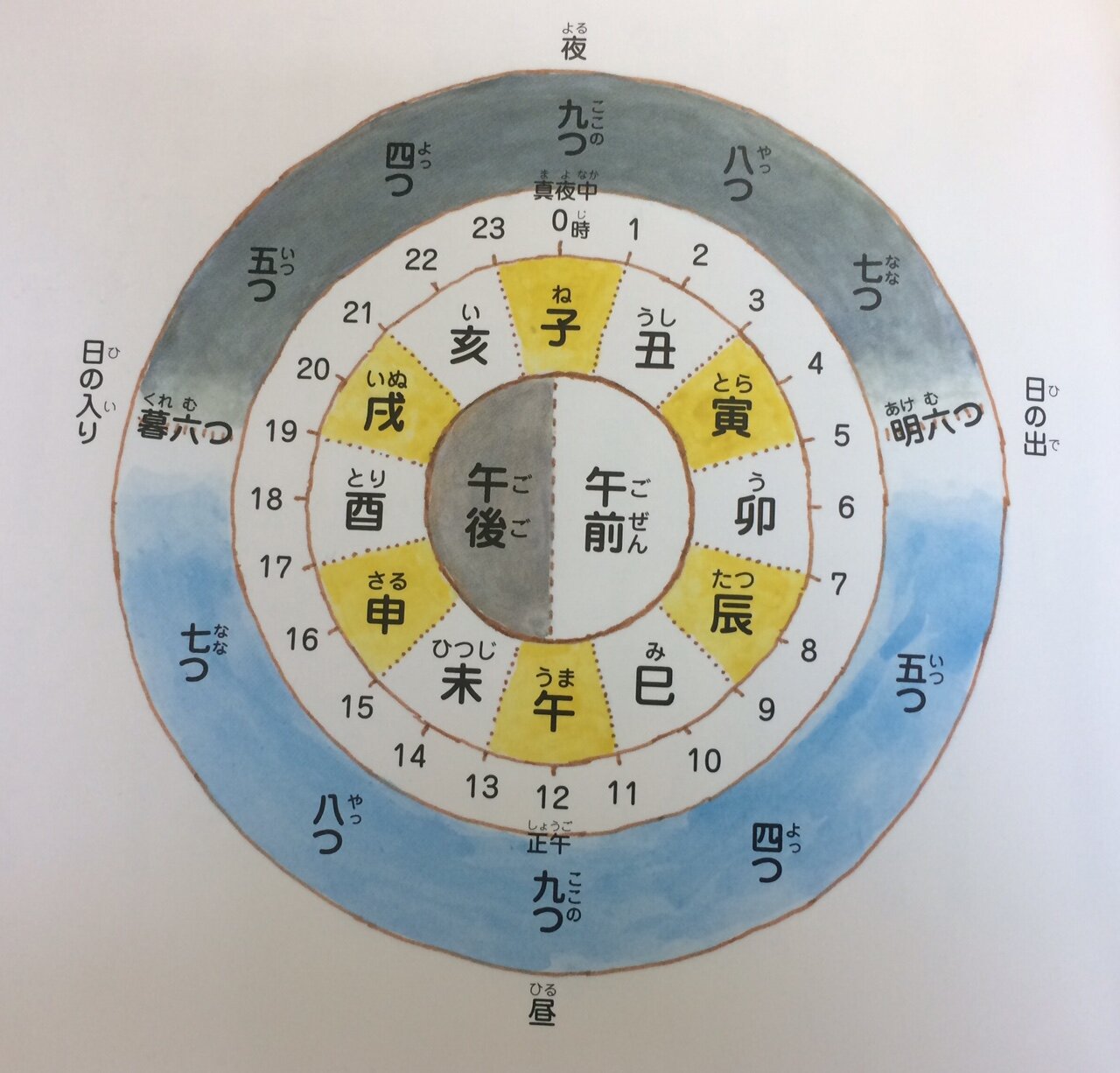

Once Upon a Time

From ancient times in Japan, time was expressed by the duodecimal system introduced from China. The hour from eleven p.m. to one a.m. was known as the Hour of the Rat (子の刻, ne no koku). From one a.m. to three a.m. was The Hour of the Ox (丑の刻の刻, ushi no koku); three a.m. to five in the morning was The Hour of the Tiger (虎の刻, tora no koku); and so on. Today, some people still say ushi mitsu doki (丑三つ時 or 丑満時), meaning in the dead or middle of night.

Later in the Edo Period (1603-1868), a bell was rung to announce the hour, so the hours of the day also came to be known by the number of times the bell was rung. At midnight and noon, the bell was rung nine times. The clock was struck every koku (刻), about once every two hours or so: nine times at noon (九つ, kokonotsu), eight times around two in the afternoon (八つ, yattsu), seven times around four-thirty in the afternoon (七つ, nanatsu), and six times at sunset (暮れ六つ, kuremutsu, lit. “twilight six”). An interesting vestige of this former system, snacks and snack time are still called o-yattsu (お八つ) and o-yattsu no jikan (お八つの時間) today. Around nine in the evening, the bell was rung five times (五つ, itsutsu); at about ten-thirty at night, it was rung four times (四つ, yottsu). And at midnight, the bell was run nine times again. In this way, the bell was rung every two hours or so, first nine times, then eight, seven, six, five, four, and then nine times again.

Another vestige of this the former system is the use of the kanji for “horse” (午) in telling time today. Twelve noon is called shōgo (正午, lit. “exactly horse”) because eleven a.m. to 1 p.m. used to be the Hour of the Horse. Anti meridiem, or a.m., today is gozen (午前, lit. “before the horse”) and post meridiem, or p.m., is gogo (午後, “after the horse”).

Another peculiarity of the former time-telling system was that although night and day was divided into twelve koku or parts, with six always referring to the sunrise and sunset. The length of the koku or “hours” varied throughout the year, such that the daytime koku were longer in the summer months and shorter in the winter months.

I will be adding more to this post in coming days and weeks.

Because one koku was on average two hours long, each koku was divided into quarters, lasting an average of thirty minutes (Ex.: 辰の一刻, tatsu no ikkoku; 丑の三つ, ushi no mitsu) or thirds (Ex.: 寅の上刻, tora no jōkoku; 卯の下刻, u no gekoku). Night and day was also divided into 100 koku. On the spring and autumn equinoxes, day and night were both 50 koku long. On the summer solstice, daytime measured 60 koku and night 40. On the winter solstice, the opposite was true.

One last interesting factoid: each domain kept its own time with noon being the time that the sun was highest in the sky. When trains were first introduced to Japan, it was not unusual for a train to leave a city in the east at say eight in the morning and arrive at a station in another prefecture in the west, say an hour later, but it was still eight in the morning. Trains not only helped industry spread throughout the nation of Japan, but also brought about the first standards in the way time was told.

Daisai

Checking out the Daimyo Machi Catholic Cathedral's website, as you do, I came across a Japanese word I'm sure few Japanese know: 大斎 (daisai).