Learned a new word today: 立志式 (risshi-shiki)

りっししき 【立志式】

【説明的に】a ceremony for fixing one's aim in life.

The Risshiki Ceremony is a ceremony for students to talk about their dreams and goals for the future, and to become aware of their responsibility as adults. It is an opportunity for junior high school students in the middle grades to reconsider their way of life and aspirations.

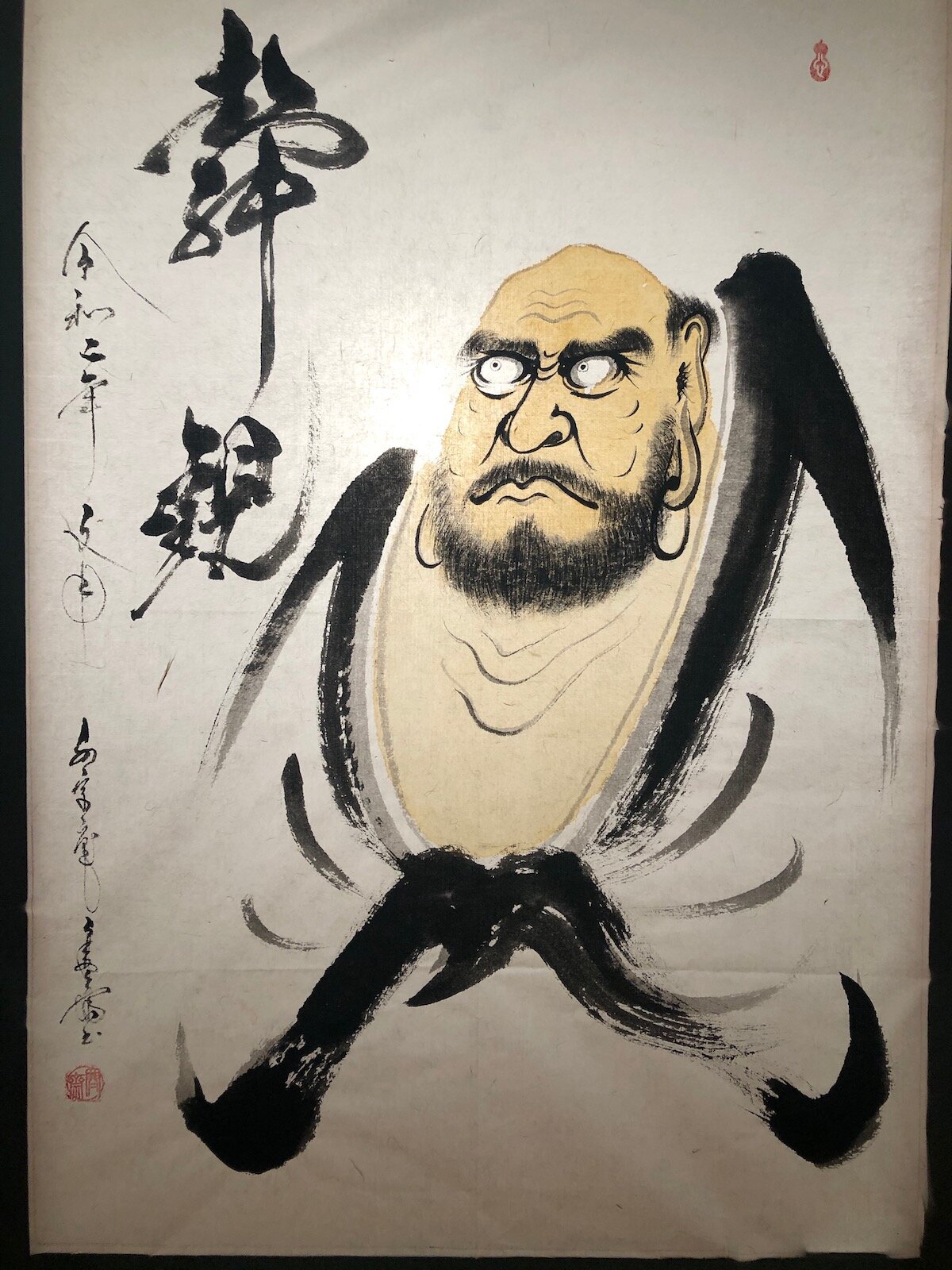

The origin of the Risshi Ceremony is the “Genpuku Ceremony” (元服) which was once held as a rite for becoming an adult. It is often held at the age of 14, when the mind and body are believed to be undergoing the transition to adulthood, and is positioned as the first step toward adulthood.

At the Risshiki Ceremony, students present their resolutions and dreams for the future. Parents and guardians may also observe the students' presentations.

Usui

Usui 雨水 Yǔshuǐ (19 February ~ 5 March)

According to the traditional Chinese calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms (jieqi, 節氣 in traditional Chinese; sekki, 節気, in Japanese), Usui (雨水, Yǔshuǐ in Chinese) is the second mini season of the year. Lasting from roughly February 19th to March 5th, Usui means “rain water”. It is the time when the first day of spring has passed and we begin preparing for the arrival of full-fledged spring. Falling snow becomes rain, and the snow and ice that have accumulated over the past several weeks melt and turn into water.

Kasumi 霞

The phenomenon in which distant objects appear blurry due to water vapor in the air and the faint cloud-like appearance that appears at this time is called kasumi, or “haze”.

Although similar to fog (霧, kiri), it is usually called kasumi in spring rather than kiri, which is the term usually reserved for the mist that occurs in autumn.

春なれや

名もなき山の

薄霞

Harunare ya

Namonaki yama no

Usugasumi

“Spring and the thin haze of a nameless mountain”

This is a haiku by Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), the famous haiku poet from the early Edo period. Looking at the thin mist that hangs over the nameless mountain, you can see that spring is in the air.

The ethereal haze hanging over the foothills of mountains and lakes can sometimes appear otherworldly, magical.

Nekoyanagi 猫柳

The Pussy willow is a deciduous shrub belonging to the Salicaceae family, which produces dense silvery-white hairy flower spikes in early spring.The flower spike of the pussy willow resembles a cat's fur, which is—no surprise—how it got its name.

Known as neko yanagi in Japanese (猫柳, lit. “cat willow”), the plant is also called senryu (川柳, lit. “river willow”) because it often grows alongside rivers.

The haiku poet Seishi Yamaguchi (1901-1994) wrote the following poem.

猫柳

高嶺は雪を

あらたにす

Nekoyanagi

Takane wa yuki o

arata ni su

“Takane Nekoyanagi renews the snow”

The silver-white fur of the nearby pussy willow shines, and perhaps the high mountains in the distance are covered in fresh snow and shine brightly. This haiku conveys the signs of spring and the harshness of the cold weather that tightens the body.

Are Kinome and Konome the same?

Although written with the same kanji, 木の芽, konome refers to the buds of trees in general. Read kinome, it refers only to the buds of Japanese pepper (山椒, sanshō).

In recent years, the two are often used interchangeably, but in the past they were used separately.

Is “Doll’s Festival” an event for girls?

March 3rd is the well-known as the Doll's Festival, or Hina Matsuri (ひな祭り). It is also called Joshi no Sekku (女子の節句)

In ancient China, there was a custom to purify oneself in the river on the Day of the Snake in early March. This is known as Jōshi no Sekku, ( 上巳の節句) and is believed to be the root of Hinamatsuri.

It is said that this festival was introduced to Japan during the Nara Period. Over time, Japanese began transferring their impurity to dolls made of paper or straw and then sending them adrift in a river (流し雛).

As time passed, these dolls began to be displayed on doll stands, and the festival evolved into the Doll's Festival.

March in the lunar calendar is also the season when peaches begin to bloom, which is why the other name Momo no Sekku (桃の節句, Peach Festival) was born.

Today, the Doll's Festival is as an event to pray for the healthy growth of girls. Until the Muromachi Period, however, it was a festival to pray for the health and safety of not only girls but also boys and adults.

Translated and abridged from Weather News.

Hempu

Interesting that hemp has long had so many varied uses in Japan except the most obvious one for the leaves and buds.

I found this graphic trying to learn the name of the straw-like material used to wrap up Obon offerings for burning. It was only when I saw the photo that I discovered that some of the items used at Obon are made from the stalk of the hemp plant, or asa.

〖植物, 繊維〗hemp ; 【亜麻】flax ; 【黄麻】jute ; 〖布〗hemp cloth ; 【亜麻の】linen ; 〖糸〗twine.

The rope, asanawa, the chopsticks, asagara-bashi, and asagara, which are used as kindling in the mukaebi fires that greet the souls of the dead, are all made of hemp. The mat in which all the offerings are rolled up and then burned is called makomogoza (真菰ご座) and is made from makomo, or the stalks of the wild water rice plant.

Okobo

. . . a soft voice called out from behind us: “Sunmahen.”

Turning around, I found a maiko mincing our way.

“Kannindossé,” she said as she passed. [1]

You could barely contain your excitement: “Wasn’t she the most adorable thing you’ve ever seen!”

We watched her walk away in that affected manner of a geisha, then disappear around a corner.

“I’ve never told anyone this, but I wanted to become a maiko myself when I was young.” [2]

“Is that so?”

“No one would have believed it. I was always so boyish as a child, climbing trees, doing karaté . . .”

“Karaté?”

“Yes, I have a green belt.”

“I’ll have to remember to never make you angry.”

“Ha-ha. Anyways, I was always playing dodgeball with the boys in my class. And now that I think about it, I didn’t even wear a skirt until junior high school when I had to because of the uniform. Until then, I was always in pants or shorts . . . Still, in the bottom my heart, I wanted to be dolled up like a maiko, and get fussed over by men. My sister, on the other hand . . .”

“You have a sister?”

“Yes, a younger sister. She’s in college right now. Mana . . .”

“Mana?”

“Yes, Mana. Kana and Mana. We once had a golden retriever called Sana-chan.”

“Funny.”

“Anyways, that sister of mine is the personification of Yamato Nadeshiko.[3] Wide-eyed, skin as white as milk, shy, but coquettish at the same time. She’s shorter than me and slightly plump, but in a good way. At any rate, she’s awfully cute and boys have been throwing themselves at her ever since she was in the fifth grade of elementary school. It’s no use fantasizing . . .”

“Oh, why not?”

“I was always too tall for one.”

“Too tall?”

“They say it all depends on the okiya, but there is a height limit of between one-hundred fifty-five centimeters and one-hundred sixty-five.” [4]

“I didn’t know that.”

“One reason is that the girls share their kimonos so they need to be about the same height. Another reason is that with their hair done up and the okobo sandals they have to wear, a maiko’s height is increased by about fifteen centimeters. I was already one-hundred sixty centimeters tall in junior high school.”

“And with all the get-up, you would have been one hundred and seventy-five centimeters tall. Interesting. I never considered that.”

[1] Sunmahen (すんまへん) is how sumimasen (すみません), or “Excuse me”, is pronounced in Kyōto and neighboring areas. Kannindossé is Kyōto-ben, or Kyōto dialect, for gomen nasai, or “Sorry” or “Pardon me”.

[2] Maiko (舞妓) is an apprentice geiko (芸妓). Traditionally aged 15 to 20, they become full-fledged geiko after learning how to dance, play the shamisen, and speak the Kyōto dialect.

[3] Yamato Nadeshiko (大和撫子) is the personification of an idealized Japanese woman: namely, young, shy, delicate.

[4] Between 5’1” and 5’5”.

The first chapter of A Woman’s Tears can be found here.

注意:この作品は残念がらフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are unfortunately fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This and other works are, or will be, available in e-book form and paperback at Amazon.

Matchmaker, Matchmaker

The word nakōdo (仲人) means "matchmaker or go-between". In the past, when arranged marriages or o-miai were more common, the nakōdo would seek out suitable prospects for a man or woman and introduce them with photos and a resume.

Now, something I didn't until very recently know about this o-miai business is the money involved. A matchmaker could earn a million yen or more for a successful match, quite a bit of cash ($10K~). And he or she would be given gifts every summer and winter until his or her death. Not a bad gig.

Insurance salesladies often took on this service as a side business as they had a large number of contacts and were privy to all kinds of private information.

Even today, when more and more couples are marrying for "love", nakōdo are still invited to perform a ceremonial role at the wedding itself. If the groom is, for instance, a doctor, he might invite one of his professors or an important doctor from his hospital to do the duty. The nakōdo will receive from ¥500,000 to over ¥1,000,000 for this service, which usually amounts to sitting in front of everyone at the wedding, making a long and tedious speech and then getting drunk.

As of today, I hereby throw my hat into the nakōdo business for the low, low cost of ¥350,000 a pop. I'm sure I can scrounge up a mourning coat somewhere and, more importantly, I promise I will not to get too stinking drunk and embarrass everyone at the nuptials.

You know where you ca--HIC--can find me.

The Way of the Bow

My long walks continued. I’d been coming down with such a severe case of cabin fever that even the heaviest of showers was no longer enough to keep me inside. I’d even traded in my flimsy convenience store umbrella for one from Paul Smith costing ten times as much, just so that I could get out of my apartment and out of my head, as often as possible. Call me Thoreau; Fukuoka, my Walden.

One afternoon, as I was returning from one of my longest walks yet that had my shins and arches aching with a dull, throbbing pain, I dropped in at the Budōkan to see what kind of martial arts were taught there.

At the entrance was a bulletin board with a schedule of classes. On Saturday evenings, big boys in diapers pushed themselves around a clay circle. Sumō wasn’t really my cup of tea, which is just as well; of all my blessings, girth is not one of them. Three evenings a week, the kendō members met to whack each other senseless with bamboo sticks. That wasn’t quite what I was looking for either.

I walked over to a small window, stuck my head in, and said excuse me in Japanese, disturbing three elderly men from their naps.

“You really gave my heart a start,” said one of the men as he approached the window.

“Um, sorry about that.”

“Wow! Your Japanese is excellent.”

“Tondemonai,” I replied reflexively. Nonsense! “My Japanese is awful. I’ve still got a lot to learn.”

“Oi, Satō-sensei. This gaijin here says his Japanese is awful, then goes and uses a word like, ‘Tondemonai!’”

Satō rubs the sleep from his eyes says, “Heh?”

“How can I help you?”

“I’m, um, looking for a kick boxing class. You got any?”

“Kick boxing? No, I’m sorry we don’t. We do have karate, though. Tuesday and Thursday evenings. And there’s Aikido on Wednesday and Friday evenings.”

“Nothing in the afternoons?”

“No, only in the evenings.”

“Well, what about jūdō?”

The man’s eyes lit up. I was in luck, there was a class in session now, he said pointing to a separate building across the driveway.

“That building?” I said. I had my doubts.

“Yes, yes. Just go right over there. Tell them you’re an observer.”

I wasn’t sure the old man had heard me correctly, but I went to the adjacent building all the same, and removed my shoes at the entrance. As I stepped into the hall, two women in their fifties wearing what looked like long, black pleated skirts and heavy white cotton tops minced past me, their white tabi’ed feet[1] sliding quietly across the black hardwood floor. A similarly dressed raisin of a man, upon seeing me bowed gracefully, then glided off to the right from which the silence was broken with the occasional “shui-pap!”

“Anō,” I called out nervously. “I was told to come here. I’m, um, interested in learning jūdō.”

“Jūdō?” the elderly man asked.

“Yes, jūdō.”

“This isn’t jūdō,” he said, eyeing me warily. “It’s kyūdō.”

“Kyūdō?” What the hell is kyūdō?

He gestured nobly in the direction the “shui-pap!” sound had emanated from and encouraged me to follow him to a platform of sorts overlooking a lawn at the end of which was a wall with black and white targets.

“Kyūdō,” the man told me again. The Way of the Bow.

He instructed me to watch an old woman who had just entered the platform carrying a bow as long as she was short. She bowed before a small Shintō household altar, called a kamidana, then minced with prescribed steps to her place on the platform. Her posture was unnaturally rigid: her arse jutted out, spine curved back. Her head was held high. With her arms bent slightly at the elbows she raised the bow upward, bringing her arms nearly parallel to the floor. She then adjusted the arrow, stabilizing the shaft with her left hand and fitting the nock onto the string with her right hand. She turned her head ever so slowly, and, fixing her gaze on the target some thirty yards away, raised her arms, bringing the bow to a point above her head.

Inhaling slowly and deeply, she extended her arms elegantly, pulling the bowstring back with her right hand, and pushing the bow forward with her left, such that the shaft of the arrow now rested against her right cheek. The old woman paused momentarily before releasing the arrow. The string snapped against the bow with the “shui-pap” I had heard before, and the arrow was sent flying majestically right on target. It fell ten yards short, landing in the grass with a miserably anticlimactic “puh, sut!”

A small, nervous laugh snuck out before I could stop it. The old man at my side gave me a nasty look then went over to the woman who had just delivered the lawn a fatal shot and praised her effusively. She remained gravely serious, bowed deeply, then bellowed: “Hai, ganbarimasu!” I shall endeavor to do my best! All the other geriatrics there suddenly came to life and also shouted: “Hai, ganbarimasu!”

When the old woman had minced away, another man came out onto the platform and went through the very same stringent ritual. He ended up shooting his arrow into the bull’s-eye of the target . . . two lanes away. He, too, was lavished with compliments by the old man, whom I’d only just realized was the sensei, the “Lobin Hood” to these somber “Melly Men and Women”, if you will.

A third man walked onto the platform with the very same gingerly steps and bowed as the others had in front of the kamidana. Standing with a similarly unnatural posture, he went through the movements before releasing his arrow. To my surprise, the arrow actually hit the target. No bull’s-eye, mind you, but close enough for a cigar. And just as I was thinking, “Now here’s someone who finally shows a bit of promise,” the sensei marched over and ripped the man a new arsehole. His form was apparently all-wrong. The poor bastard looked thoroughly dejected as he slinked off the platform.

I went back to the Budōkan the following day to begin kyūdō lessons in earnest, not so much out of a burning passion for the martial art itself as a consequence of an adherence to the Taoist doctrine of wu wei—the art of letting be, or going with the flow: I had got this far, and was curious where it might take me. It was a mistake, although I didn’t know it at the time.

The adorable Hirose Suzu in a Kyūdō-gi.

I didn’t want the other members at the Budōkan to think of me as a mikka bōzu, that is a-three-day monk, which is what they called quitters here, but of all the martial arts I could have ended up doing, kyūdō must have been zee vurst. Being pushed around by big boys in diapers in the sumō ring would have been a vastly more entertaining.

My training progressed with unnervingly small baby steps with each visit to the dōjō. During the first several lessons, I was not allowed to even touch a bow. Instead, I was made to practice how to step properly into and then walk within the staging area. Oh yes, and how to bow reverently before the goddamn kamidana.

After weeks of mincing effeminately, I was allowed to move on to the next stage which involved going through the elaborate ritual of holding the bow, threading the nock with the bow string, aiming and releasing the arrow. Problem was, I had neither bow nor arrow and was asked, rather, to rely on my fertile imagination. Several days of this humiliation were followed by at last the opportunity to hold a bow and practice releasing imaginary arrows at an imaginary target. After the hour-long practice, I would have tea with my imaginary friends.

[1] Tabi are Japanese socks that have the big toes separate from the other toes, like mittens for your feet.

Excerpt from A Woman's Nails. To read more, go here.

© Aonghas Crowe, 2010. All rights reserved. No unauthorized duplication of any kind.

注意:この作品はフィクションです。登場人物、団体等、実在のモノとは一切関係ありません。

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A Woman's Nails is available on Amazon's Kindle.

Nodaté

In spite of the fact that I spend a good part of every day with my nose in a Japanese-English dictionary, I seldom come across a completely new word anymore.

I don't mean to imply that my Japanese vocabulary is already so rich or that sentences roll off my tongue like polished jewels. It isn't and they don't. But nowadays whenever I encounter a new word, I find that if I can visualize the kanji that combine to form the word, I can usually guess what the meaning is.

The other day, I was talking with a friend who is a successful restauranteur. He had recently opened up motsu nabe restaurant in Hokkaidō and I was curious to know how he and another friend, who has a chain of yakiniku restaurants in Fukuoka and Tōkyō, could be so consistently successful despite wild fluctuations in the business climate over the past ten years. He answered, "Gūzen-wa hitsuzen." (偶然は必然 (ぐうぜんはひつぜん) literally "Coincidence is inevitable”, but more closer to “Not coincidence, but destiny!”)

He asked me if I knew what hitsuzen meant. I didn't actually, but said I did, because I guessed that the word was written 必然 (ひつぜん), where 必, hitsu orkanarazu, meant "certainly, surely, always", and 然, zen, was a suffix that meant "in that way". I could get the gist of what he was talking about which is usually enough. Not always, but usually.

I sometimes joke that I can understand 90% of the Japanese I read and hear. That may sound impressive until you realize that the remaining 10% is often the most important part of what is being conveyed.

So, it is with nerdish delight when I come across a word that taxes my imagination and yet finds me coming up short of that eureka! of comprehension.

Yesterday, another business man I know, who runs a Doctor Martens boutique and shoe-wholesaling business, told me he had bought a nodatê (野点). I had no idea what he was talking about, so I googled it and found pictures of the large cinnabar-colored paper umbrellas used when the tea ceremony is conducted outdoors. I can't count how many times I've seen them, but never knew what they were called. I would even venture to say that your average Japanese, who hasn't been initiated into the arcana of the Way of Tea, probably doesn't know what they're called, either.

Now I do.

Something else I didn't know yesterday, was the word tateru (点てる、たてる) describes the state in which someone is drinking maccha. It's an unusual reading for the kanji 点 (usually read as ten) and doesn't show up in many dictionaries.

「点てる」は“抹茶をいれる”の意。「お茶を点てる」from my 「スーパー大辞林」

The Good Levite

Got a call from a credit card company, saying that my credit card has been found.

“My card? What card?”

“Your Walmart card.”

Walmart? Do I even have a Walmart card? I rifle through my box of neglected mail and bills and other crap and find an envelope from the credit card company. The card is there in the envelope it came in. But wait! Why do I have two, no, make that three, including a highway ETC card? When did I get that? Why, I don’t even drive. And one of them is only used for processing my rent payment (a Japanese thing).

“And how could I lose the card if I never carry it?” I ask absent-mindedly.

“It was found at the XYZ hotel in Okinawa.”

“Oh . . . And?”

“They turned it over to the police, so if you want it back you have to contact them . . .”

“Okay . . .”

I still can't figure out how on earth I could have lost a card I still have, but . . . Hmm.

After hanging up, I check the number I was given to see if it was legit. Yep, it's the Ishikawa Police Department in the town where our hotel is located.

I think about this for a while and go through my bank books to see if I've been billed for something I didn't buy and . . . Nope. Nothing out of the ordinary.

Then it dawns on me that I may have taken an old wallet—which I'm apt to do—that has only a few necessary items in it, such as my gaijin card, insurance card, a cash card, credit card, and so on. The old credit card must have been tucked inside the wallet and fallen out in the safety deposit box or something.

So odd. It just doesn’t add up. A Walmart card?

At first I thought I was being phished, but the woman from the credit card company didn't ask me for any personal information or credit card details. She wouldn't even give me details about the nature of the card (expiration date, etc.) that had been found.

So, I decide to call the cops in Ishikawa on Tuesday to see if my hunch was right.

Several hours later my wife returns home. I tell her about the call.

“Ah! I was wondering what happened to that card!”

I bang my head against the table. Now I understand. She had the credit card made to get points at the local supermarket, which is a subsidiary of Walmart, and used my name but never told me about. (That qualifies as fraud, doesn’t it? Good thing I love her.)

Later, I went online to double check whether the card had been used, but fortunately it hadn’t. Just to be on the safe side, I had the card replaced.

When we called the Ishikawa Police Department on Tuesday, we learned that my wife had lost some 10 cards in total. Most were point cards for supermarkets and so on.

I said to my wife: “You know, if it had been me who lost all those cards and didn’t realize it for three whole months, you would never let me hear the end of it.”

She apologized sheepishly and I let it slide, as I always do.

And speaking of lost and found . . .

During my walk this morning, I found a briefcase behind the hedge of one of my favorite restaurants.

"Someone has lost their bag," I said to my wife who was a few paces ahead of me. Looking inside, I could see that it was full of documents. There was a wallet, too, chockablock with credit cards and other cards. "The wallet's inside, too."

But, so was a belt. Odd, I thought.

"Maybe we should take it to the police box . . .," I suggested.

Then I noticed a pack of cigarettes a yard a way . . . and a necktie . . . clearly it all belonged to a salaryman who must have been blind drunk last night. He'd be up a creek when he woke and discovered that it was missing, I thought. I know how I'd feel . . . And there in the corner, next to the hedge was a huge, wet turd.

"Ah, Christ! The guy took a dump in the corner!"

My wife let out a little yelp. "Gross! Just leave where it is!"

“I’m not touching the poop!”

“Not the poop. The bag! Leave the bag!”

I couldn't help but agree, the Good Samaritan in me shoved away by the Levite.

I put the bag down and started to walk away. On second thought, I went back and wiped down the places I had touched, such that my prints wouldn't be left. Better safe than sorry, right?

So, if you know anyone who is missing his briefcase and is probably hungover. Tell him I know where he can find it and his "noguso".

Bumped into one of my students last year and got molested by her mother. Seriously. The woman pinched my arse.

Coming of Age

For someone like me who is fascinated by Japanese traditions and culture, Seijin-no-hi, or Coming-of-Age Day, held on the second Monday of January, is one of the many days to look forward to in Japan. For on that day, you can find many young women, dressed in elaborate kimono, their hair coiffed, make-up and nails perfect—a stunning display of beauty like exotic monocarpic flowers, blooming once after 20 years of growth. Although men, too, occasionally dress in flashy kimono their hair done up in wild pompadours, most of them wear conservative suits more befitting of the occasion. But let’s be honest, I’m much more interested in the women.

The modern version of Seijin-shiki began in Warabi City, Saitama on 22 November 1946. The Pacific War had ended half a year earlier and much of Japan lay in ruins. The ceremony, called Seinensai (青年祭, lit. “Youth Festival”) was held to encourage the young people of that broken country to rise up and dispel the dark mood of the times. Two years later, the ceremony was established as a national holiday originally held on the fifteenth of January. The original date is significant in that before the adoption of the Gregorian Calendar, the full moon fell on the fifteen of every month in Japan, and the fifteenth day of the firstmonth of the year was known as Ko-shōgatsu (小正月, lit. “little New Year”), the day that New Year’s had been traditionally celebrated until the Edo Period. Thanks to the “happy Monday system”, however, the date of Seijin-shiki has been held on the second Monday of January since the year 2000.

While today’s Seijin-shiki has its roots in the immediate post-war years, the rite of passage can actually be traced back to the Nara Period (710-794). In those days, genpuku (元服)—a coming-of-age ceremony modeled, like so many things in that era, after the customs of the Tang Dynasty of China (618~907)—was held for boys between the ages of 10 and 20 (some sources say between 12 and 16). In the genpuku ceremony, which literally means “head” (元) wearing” (服), a boy’s hair was fashioned in the manner of an adult’s, and he no longer wore the clothing of a child (see below). Moreover, his birth name was exchanged for an adult one, or eboshi-na (烏帽子名), and he was given a brimless ceremonial court cap, or kanmuri (冠). The adoption of the new hairstyle and clothing signified the assumption of adult responsibilities.

Women, on the other hand, would receive a long pleated skirt called a mogi (裳着), to replace the wide-sleeved, unisex hakama-githey wore as children. The timing of a woman’s coming-of-age came typically after menarche, or in her early to late teens, and indicated that she was of marriageable age. While that may seem scandalously young to us in 2021, during the Nara Period, the life expectancy was between 28 and 33, and would get progressively shorter over time rather than longer. In the Muromachi Period (1336~1573), the average life expectancy was a mere blip of 15 years. Imagine that.

In the past, coming-of-age ceremonies were for the most part limited to those in the higher echelons of Japanese society which included the nobility and kugé aristocratic class, and from the Kamakura Period (1185~1333) on, the samurai warrior class, as well.

Children of the court prepared for roles they would assume later on from as young as three or four years of age, studying court ceremonies, Buddhist doctrine, and ethics. Later, they moved on to mastering the skills of calligraphy, which in classical times was indispensable for a courtier.

In the age of the samurai, from the Kamakura to the Edo Periods (1185~1868), the genpuku ceremony featured the placing of a samurai helmet, rather than a court cap, on the head of the new adult male. During periods of unrest such as the Sengoku Jidai, or Warring States Period, (1467~1615), genpuku was often delayed until a son was full-grown in order to spare the inexperienced warrior the duty to fight, and most likely die, in battle. As peace reigned, however, the age considered appropriate for coming-of-age was lowered in response to pressures to marry and produce heirs, which could not happen until after the ceremony had been performed. In the sixteenth century, the average coming-of-age ceremony for samurai was 15 to 17, and by the 1800s it had dropped to 13 to 15.

Today, both men and women, who will reach the age of adulthood, i.e. twenty, by April 1, take part in the modern-version of Seijin Shiki. The ceremony is held at a venue in the city or town where the new adult resides. There, government officials make speeches and hand out presents. For many of the participants, the day is considered a class reunion of sorts because after the ceremony, they often meet friends from their junior high school at a formal party organized by their former classmates.

Why do women today wear the long-sleeved furisode kimono?

If my reading of the Japanese is correct, and do correct me if it isn’t, but in the past the furisode that young unmarried women of means wore had much shorter sleeves. Youths, both male and female who were not yet old enough, wore what is known as fudangi, or everyday kimono. As Japan entered the Edo Period, though, the design of furisode gradually came to resemble that of today’s furisode. The longer and more exaggerated the sleeves became, the more impractical they were for everyday use, and eventually came to be reserved as formal attire for unmarried women. By the Shōwa Period, furisode had become established as a costume worn only on special occasions, such as Coming-of-Age Day and weddings. The swinging of the long sleeves of the kimono themselves is said to act as a kind of talisman against evils (魔除け) or drive out evil spirits (厄払い).

This year with the coronavirus pandemic still raging we could use some good luck charms. Unfortunately for those Japanese who have been anticipating the day, many local governments have either cancelled or postponed their planned Coming-of-Age Day ceremonies. As far as I know, Fukuoka City is still going ahead with its event, which will be held at Marine Messe. The ceremony will be shortened and split into two groups in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The event will also be live-streamed so that others can attend virtually.

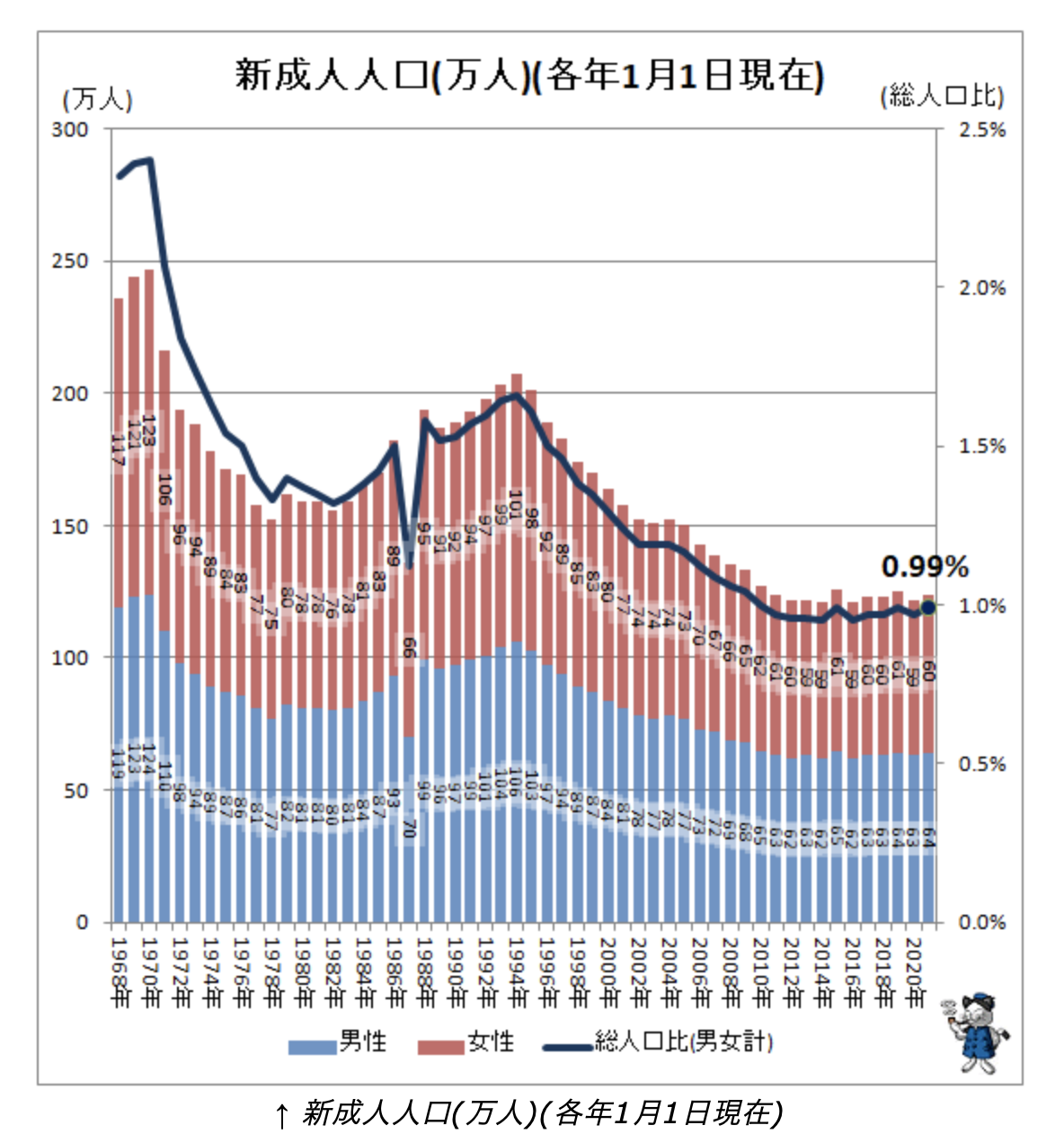

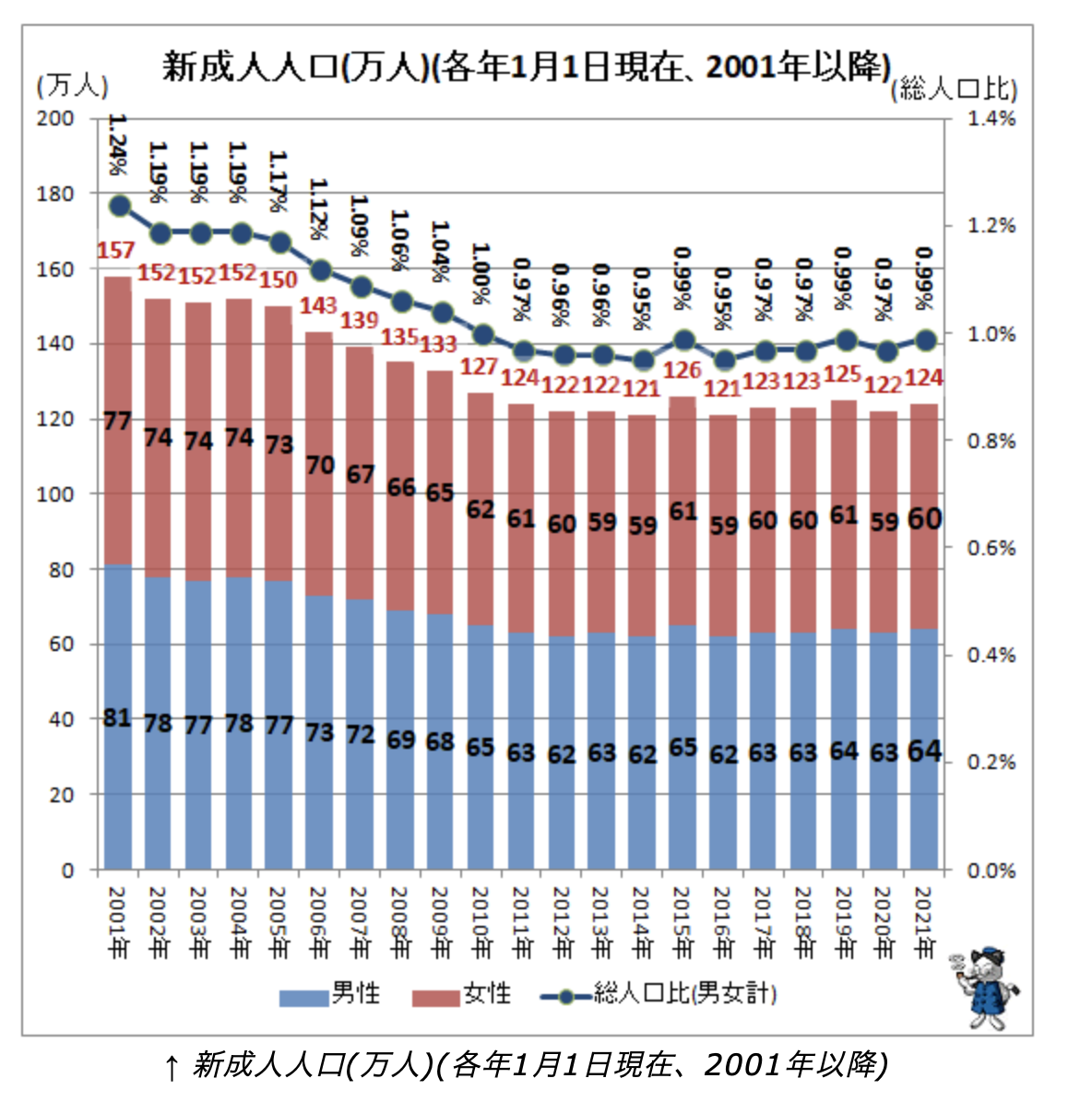

In 2021, there will be 1,240,000 “new adults” or shinseijin (新成人), an increase of 200,000 over last year. For the past 11 years running, the percent of population represented by these new adults has been less than 1%.

The dark navy line indicates the percentage of “new adults” relative the general population. Red is the total number of females—blue, males—who are recognized as adults on the second Monday of January.

Note that in 1987, the number of new adults dropped dramatically. The 20-year-olds were born in 1966, or the Year of the Fire Horse (丙午, Hinoe Uma). Due to the belief that people born on this year have a very strong personality, birthrates in Japan tend to see a sharp decline.

This is the same graph as the one above, only focused on the past 20 years.

You might be curious to know how much the whole Seijin Shiki kit and caboodle costs. As a parent, I certainly am. In 2020, just under half of the women attending the ceremony rented their furisode kimono; whereas the other half either borrowed one from their mother, elder sister, or other relative, or bought it outright. The percent of those who bought theirs last year was up over 5% over the previous year.

Rental (orange) 48%, down from 53%; borrowed from “Mama” (gray) 25%, up from 20%; bought (dark blue) 19%, up from 13%; borrowed from a sister or relative (yellow), 6%, down from 7%.

As you can see, the percent who rent their kimono (orange) has increased over the years. Those who bought theirs (gray) ticked up last year.

So, how much will renting a furisode kimono set you back? That depends, of course, on the shops, the services they provide, and the kimono itself. The cheapest rental furisode, made, I believe, cardboard origami and duct tape, go for about ¥40,000, but the going rate is closer to ¥250,000. Yes, you read that correctly. New furisode can cost over ¥300,000 to rent, not buy. The more expensive the rental, the more services will be included—kitsuke (helping the woman get dressed), hair setting, make-up, nails, and all that. Some rental salons will also take your photos which is usually done several months before Coming-of-Age. Over half of women report preparing for the day in the first six to eight months of the year prior to the ceremony.

As we have seen above, buying the furisode kimono is the option 20% of the women choose. But how much does a new kimono for a new-adult cost? Once again, prices vary. A single kimono can run ¥150,000 ~ ¥600,000, depending on the material it’s made from and the tailoring. While much more expensive than renting, the kimono can be used again at the graduation ceremony or at weddings and handed down to younger sisters or even one’s own children in the future, saving you money in the long run. If on the other hand you cannot envision ever wearing the furisode again in the future, then you are better off renting. At any rate, if you have a daughter or two, start saving your “yennies”.

In recent years, elementary schools have been holdingni-bun-no-ichi seijin-shiki (二分の一成人式) or “Half Coming-of-Age Day Ceremonies” for fourth graders who have become ten years old. Parents are invited to school where their children read letters of thanks to them. This year, like so many events will probably be cancelled or conducted without parents.

Ringing In The New Year

I used to get so depressed after Christmas when I was young. In America, there really wasn’t much to look forward to once King of All Holidays had passed. We had Easter, of course, but you had to first eke your way through six weeks of Lent, which was no easy task in my devoutly Roman Catholic family.

After coming to Japan, though, I haven’t had that problem. Here, there is always something in the offing to look forward to: Ōmisoka, or New Year’s Eve; Gantan or New Year’s Day itself; the first seven or fifteen days of the New Year called Matsunouchi; the Tōka Ebisu Festival held around the 10th of January; Dondoyaki on the 15th; Setsubun at the beginning of February, and so on.

And so, to keep those Christmas Blues in check, we have made it a habit to decorate our home if not as lavishly, then just as festively for the New Year. That involves a trip to one of my favorite florists, Unpas. Every year they make the most wonderful shimenawa and mini kadomatsu.

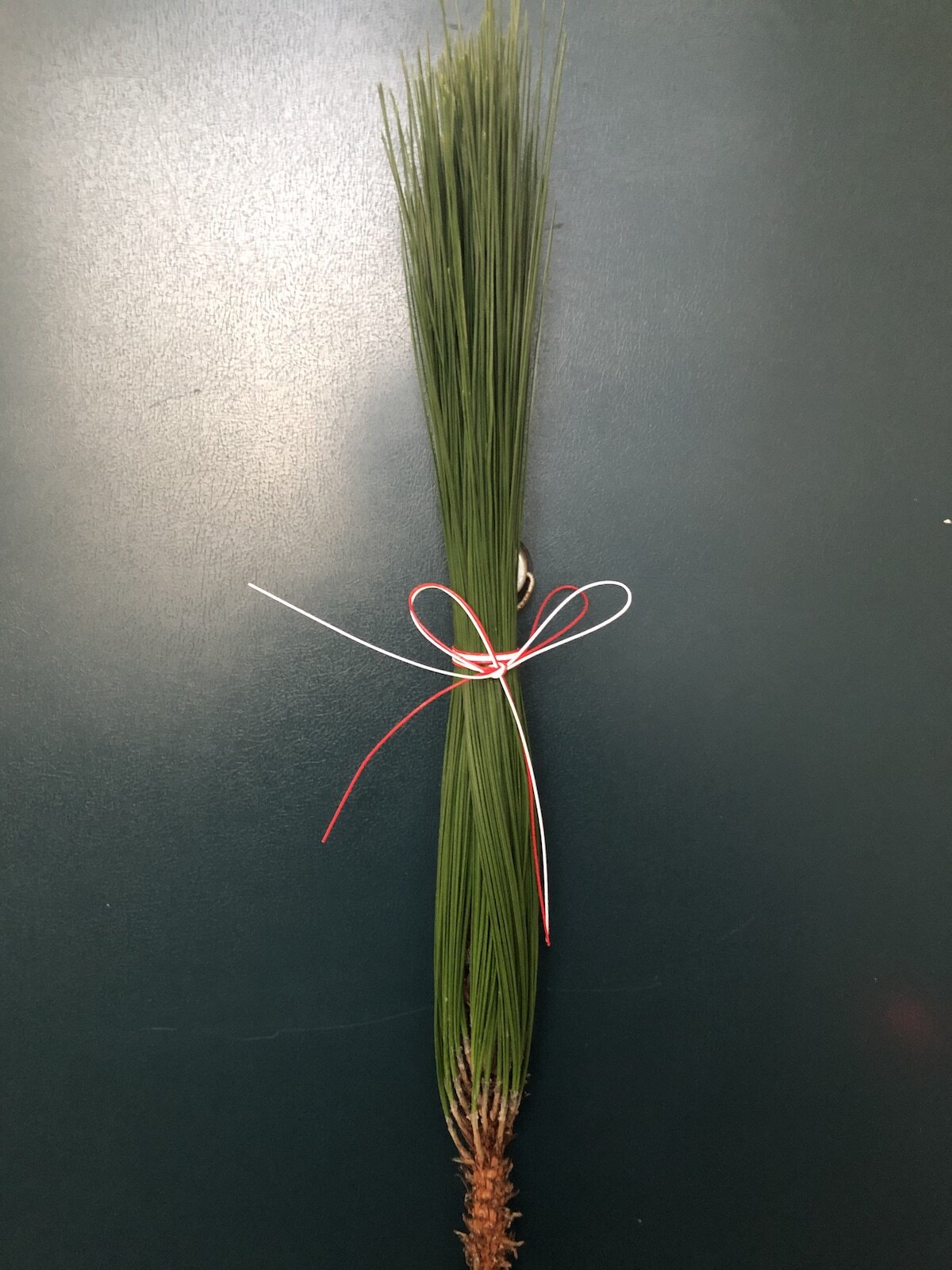

This year, in keeping up with the muted mood of the times, we opted for a simple design.

We may add something to this pine branch to make it a bit more colorful.

A few days later, we went to the Yanagibashi Shōtengai market, which is always hopping with at the end of the year, picking up New Year’s decorations and ingredients to make traditional New Year’s dishes.

I think this may be the first time we have ever bought a real kagami-mochi. I think we may have started a new tradition.

What is a kagami mochi you want to know?

Let’s ask Mr. Wiki:

Kagami Mochi (鏡餅, "mirror rice cake"), is a traditional Japanese New Year decoration. It usually consists of two round mochi (rice cakes), the smaller placed atop the larger, and a daidai (a bitter orange) with an attached leaf on top. In addition, it may have a sheet of kombu and a skewer of dried persimmons under the mochi. It sits on a stand called a sanpō (三宝) over a sheet called a shihōbeni (四方紅), which is supposed to ward off fires from the house for the following years. Sheets of paper called gohei (御幣) folded into lightning shapes similarto those seen on sumo wrestler's belts are also attached.

The kagami mochi first appeared in the Muromachi Period (14th–16th century). The name kagami ("mirror") is said to have originated from its resemblance to an old-fashioned kind of round coppermirror, which also had a religious significance. The reason for it is not clear. Explanations include mochi being a food for special days, the spirit of the rice plant being found in the mochi, and the mochi being a food which gives strength.

The two mochi discs are variously said to symbolize the going and coming years, the human heart, "yin" and "yang", or the moon and the sun. The "daidai", whose name means "generations", is said to symbolize the continuation of a family from generation to generation.

No-Show-Gatsu

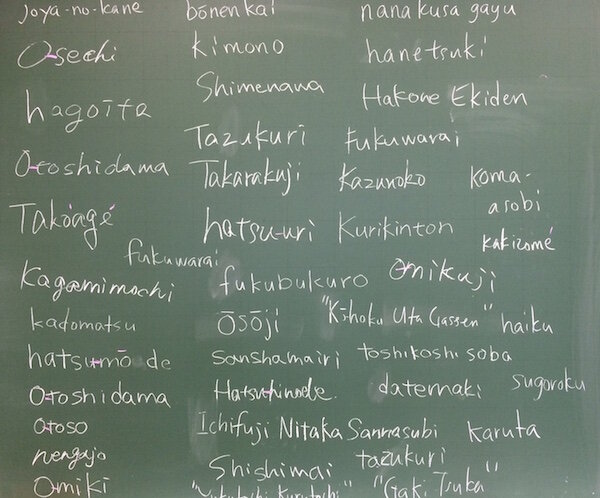

In recent years, I have been doing the following activity on the first class after the winter break.

I split the class up into teams and, while listening to traditional Japanese music featuring the koto or shamisen, I have the students write on the blackboard as many words as they can in rōmaji related to the Japanese New Year.

In addition to being kind of fun—not barrels of fun, mind you, but fun enough—this activity can be rather instructive.

For starters, you'll find that many Japanese students, not being proficient in the Hepburn romanization, will write things such as fukubukuro with an "h" rather than an "f" (hukubukuro) or nengajō with a "y" (nengajyo). The reason for this is that many Japanese learn simpler forms of romanization known as kunrei-shiki or Nihon-shiki. For more on this, go here. This is a good chance to briefly re-introduce the students to the Hepburn romanization and encourage them to use it in the future.

A few years back, my second-year English Communication majors came up with the following words:

One of the interesting things about this is that while many Japanese students will offer up words like hagoita, a decorative paddle used when playing a game resembling badminton called hanetsuki or even tako-agé (kite-flying), you shouldn't expect to see any of your neighbors playing hanetsuki or flying kites on New Year's Day. (In all my years in Japan, I have never once seen young women in kimono playing this game live as I have in television dramas.)

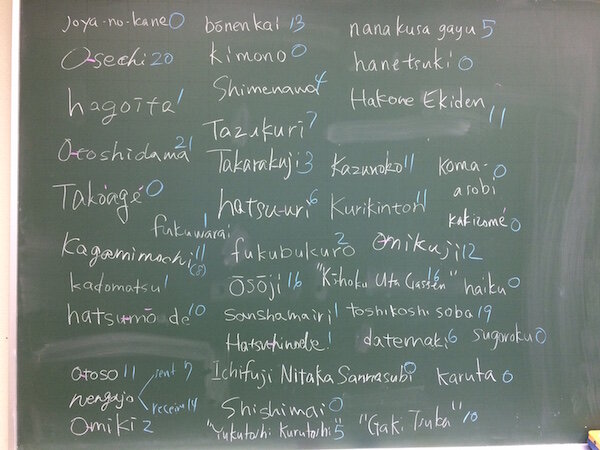

I then tell the students to ask one another if they had done any of the things on the board.

"Did you eat o-sechi or nana-kusa gayu?"

"Did you decorate your homes with shimenawa and kadomatsu?"

"Did you send any nengajō?"

Of the 23 students who attended that day, twenty had eaten o-sechi, four had a shimenawa at the entrance of their homes, six had gone to the hatsu-uri New Year's sales, eleven had drunk o-toso, and so on.

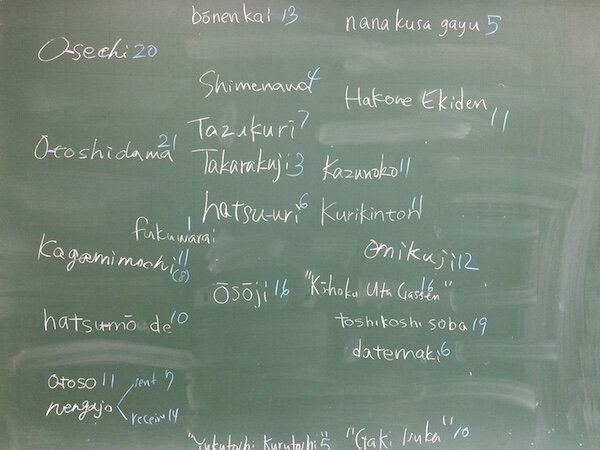

Erasing those items which few or none of the students had partaken of, we came up with the following significantly pared down list:

Where New Year's in Japan was once a very colorful, tradition-laden event, all that remains of it today, or so it seems, is the food, the shopping, and banal TV programs. Less than half of the students visited one Shintō shrine (hatsumōde), let alone three, during the holiday. It's kind of sad when you think about it.

Now, I'm not suggesting that we need to put the Shintō back in the Shinnen (New Year), like some good Christians back home demand Christ be kept in that pagan celebration of the winter solstice also known as Christmas. But, I find it odd that the Japanese are so lackadaisical when it comes to their own heritage and culture.

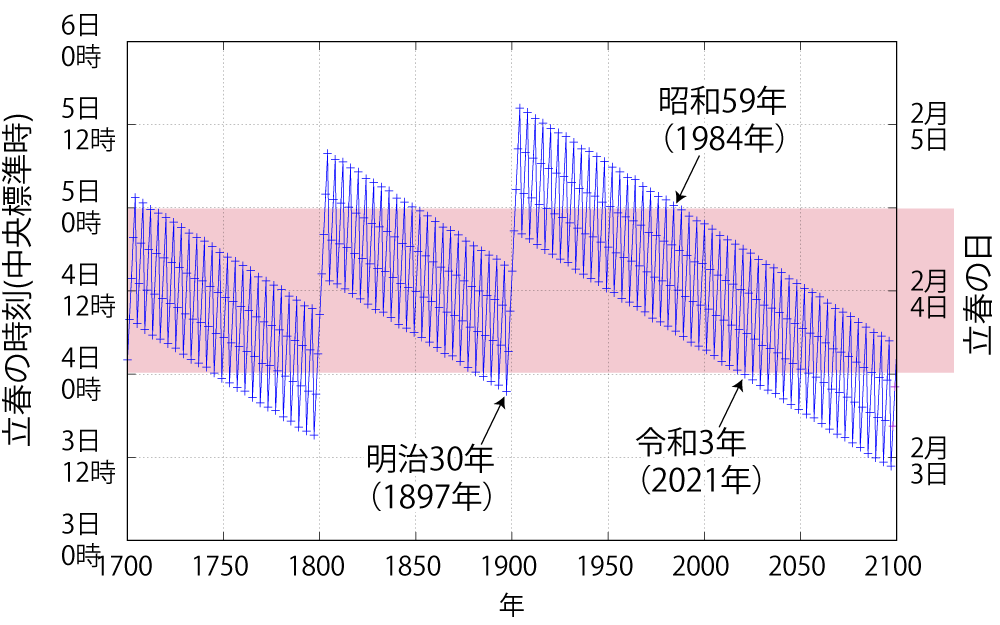

Setsubun 2021

Next year, Setsubun will fall on February 2 for the first time in 124 years. This will also be the first time in 37 years that the seasonal ritual is not February 3rd.

For more, go here:

https://eco.mtk.nao.ac.jp/koyomi/topics/html/topics2021_2.html

Mitama Matsuri

Gokoku Jinja holds a special place in my heart. It was, in fact, where I was first married. And, though, that first marriage could hardly be called a success (My second marriage in a Christian church in Honolulu has fared much better), I still have many fond memories of that wedding day.

The Mimata Matsuri, or the Souls' Festival that is held from the 13th to the 16th at Gokoku Jinja.

Like the similarly named festival at Tōkyō's Yasukuni Shrine, Gokoku's Mitama Matsuri is a festival in honor of those who died in the service of the country. That may sound sinister considering Japan's history, but (at least here in Fukuoka) all this really involves is lanterns being displayed on the grounds of the shrine.

The first time I discovered the "festival" was about fifteen years ago, during one of my evening jogs. Seeing the lanterns, I took a detour and headed into the shrine. There were only a handful of people milling about, but the lanterns must have numbered in the tens of thousands. It was awe-inspiring.

In recent years, the shrine has tried with a modicum success to attract more visitors by offering concerts, food stalls, and other attractions. Unfortunately, the number of lanterns steadily falls year by year and the feeling of awe that struck me the first time has become tempered with disappointment.

Seventy-five years have passed since the end of World War II and those who participated in it are now in their 90s and older, if still alive. Those who lost parents, children, siblings, or spouses in the war, people who'd be most inclined to keep a lantern burning for the souls of loved ones, are even older, more infirm (again, if alive). My own Japanese grandmother, who died about five years ago, lost her husband in the war. The more that time passes since the end of hostilities in the Pacific, the easier it is for me to imagine that the yearly calls of "Never again" might one day become too faint to prevent another destructive war. Just a thought.

Fidelium animae, per misericordiam Dei, requiescant in pace. Amen.

Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them. May the souls of the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace. Amen.

_______________________________

Note: "The origin of Yasukuni Shrine is Shokonsha established at Kudan in Tōkyō in the second year of the Meiji era (1869) by the will of the Emperor Meiji. In 1879, it was renamed Yasukuni Shrine.

"When the Emperor Meiji visited Tōkyō Shōkonsha for the first time on January 27 in 1874, he composed a poem; "I assure those of you who fought and died for your country that your names will live forever at this shrine in Musashino". As can be seen in this poem, Yasukuni Shrine was established to commemorate and honor the achievement of those who dedicated their precious lives for their country. The name "Yasukuni," given by the Emperor Meiji represents wishes for preserving peace of the nation.

"Currently, more than 2,466,000 divinities are enshrined here at Yasukuni Shrine."

-- From Yasukuni's official home page

Doyo no Ushi

On Tuesday, you will probably be seeing 土用の丑 (doyō no ushi) on signs at your local supermarket or izakaya. What the hell is this?

Doyō (土用) refers to the 18 days before the change of a season (節分). In the case of 7/21, it refers to the 18 days before the start of autumn or rishhū (立秋), lìqiū in Chinese. This year rishhū is on August 7th.

The beginning of this 18-day period is known as 土用の入り (doyō no iri); the final day, 節分 (setsubun). Yes, there is more than one "setsubun" in Japan—four actually—not just the one in February when people play exorcist and throw beans at demons.

As it is believed that one becomes susceptible to all kinds of ailments when seasons change, the Japanese like to fortify themselves with unagi (grilled eel, pictured), udon, and umeboshi (pickled plums). Why these things? Because they start with "u", just like the "u" in "doyō no Ushi". Yes, that is the reason. Silly, ain' it?

The "do" in "doyō" incidentally means earth/soil, and is one of the five ancient elements, 五行 (Gogyō, or wǔxíng in Chinese). These five elements (fire, water, wood, metal/gold, earth) are also the same as the days in the week. Most people believe these came from China, but they actually came from the Roman Empire, which created the 7-day week and gave us the names for the days which today are still reflected in the Japanese--namely, Nichiyōbi (Sun Day), Getsuyōbi (Moon Day), Kayōbi (Mars/FIre Day), Suiyōbi (Mercury/Water Day), Mokuyōbi (Jupiter/Wood Day), Kinyōbi (Venus/Metal Day) and Doyōbi (Saturn/Earth Day). The order of the days, I believe, was connected to the speed at which they passed through the sky. (I need to double check that.) Interestingly, in Chinese, they just call the days "the first day of the week, the second day of the week", which is kind of what you would expect of a humorless and Godless, Communist dictatorship.

The "ushi" in dōyo no ushi means cow. (As you may know, there are 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac. 12 animals x 5 elements gives us 60 different combinations.)

And so what "dōyo no ushi" actually means is this: "the day of the cow that falls within in the 18 days before the start of a new season according to the ancient luni-solar calendar."

Got that?

But wait! If there are only 12 elements and 18 days of the doyō period, then there must be two doyō no ushi days. Yes, you're right. At least in most years you are. This year, there will be two doyō no ushi. The first (一の丑, ichi no ushi) falls on July 21st; the second (二の丑, ni no ushi), on August 2nd.

Bon appétit!

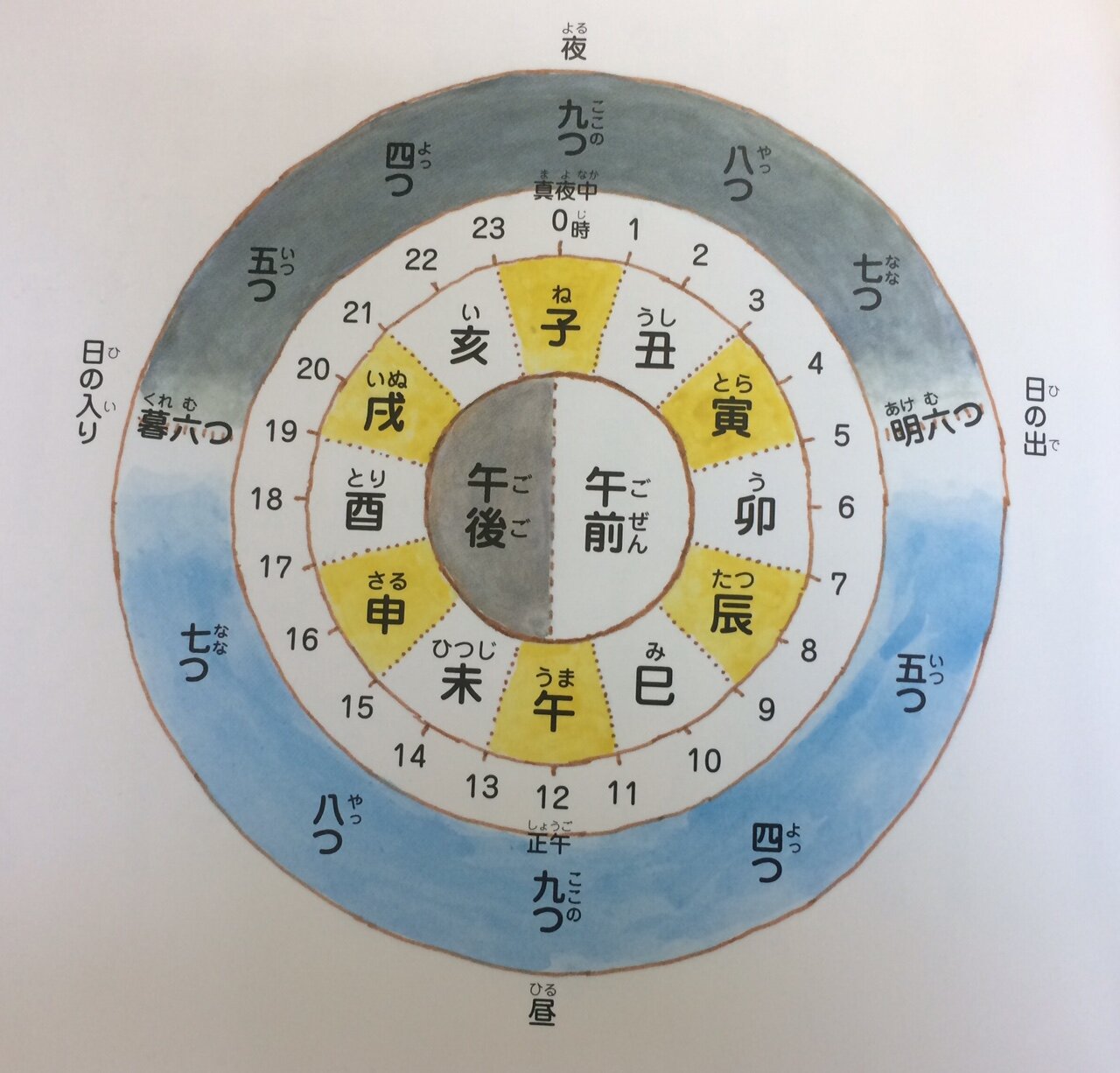

Once Upon a Time

From ancient times in Japan, time was expressed by the duodecimal system introduced from China. The hour from eleven p.m. to one a.m. was known as the Hour of the Rat (子の刻, ne no koku). From one a.m. to three a.m. was The Hour of the Ox (丑の刻の刻, ushi no koku); three a.m. to five in the morning was The Hour of the Tiger (虎の刻, tora no koku); and so on. Today, some people still say ushi mitsu doki (丑三つ時 or 丑満時), meaning in the dead or middle of night.

Later in the Edo Period (1603-1868), a bell was rung to announce the hour, so the hours of the day also came to be known by the number of times the bell was rung. At midnight and noon, the bell was rung nine times. The clock was struck every koku (刻), about once every two hours or so: nine times at noon (九つ, kokonotsu), eight times around two in the afternoon (八つ, yattsu), seven times around four-thirty in the afternoon (七つ, nanatsu), and six times at sunset (暮れ六つ, kuremutsu, lit. “twilight six”). An interesting vestige of this former system, snacks and snack time are still called o-yattsu (お八つ) and o-yattsu no jikan (お八つの時間) today. Around nine in the evening, the bell was rung five times (五つ, itsutsu); at about ten-thirty at night, it was rung four times (四つ, yottsu). And at midnight, the bell was run nine times again. In this way, the bell was rung every two hours or so, first nine times, then eight, seven, six, five, four, and then nine times again.

Another vestige of this the former system is the use of the kanji for “horse” (午) in telling time today. Twelve noon is called shōgo (正午, lit. “exactly horse”) because eleven a.m. to 1 p.m. used to be the Hour of the Horse. Anti meridiem, or a.m., today is gozen (午前, lit. “before the horse”) and post meridiem, or p.m., is gogo (午後, “after the horse”).

Another peculiarity of the former time-telling system was that although night and day was divided into twelve koku or parts, with six always referring to the sunrise and sunset. The length of the koku or “hours” varied throughout the year, such that the daytime koku were longer in the summer months and shorter in the winter months.

I will be adding more to this post in coming days and weeks.

Because one koku was on average two hours long, each koku was divided into quarters, lasting an average of thirty minutes (Ex.: 辰の一刻, tatsu no ikkoku; 丑の三つ, ushi no mitsu) or thirds (Ex.: 寅の上刻, tora no jōkoku; 卯の下刻, u no gekoku). Night and day was also divided into 100 koku. On the spring and autumn equinoxes, day and night were both 50 koku long. On the summer solstice, daytime measured 60 koku and night 40. On the winter solstice, the opposite was true.

One last interesting factoid: each domain kept its own time with noon being the time that the sun was highest in the sky. When trains were first introduced to Japan, it was not unusual for a train to leave a city in the east at say eight in the morning and arrive at a station in another prefecture in the west, say an hour later, but it was still eight in the morning. Trains not only helped industry spread throughout the nation of Japan, but also brought about the first standards in the way time was told.

Ishiganto

Walking down a cobbled slope in the Kinjō-chō neighborhood just south of Shuri Castle in Naha, Okinawa, I spotted a sign usually overlooked by tourists who can't read kanji: 石敢當

Ishigantō are ornamental tablets or engravings placed near or in buildings and other structures to exorcise or ward off evil spirits. Shí gǎn dāng, as they are called in Mandarin Chinese, are, according to Mr. Wiki, "often associated with Mount Tai [north of the city of Tai'an in Shandong province] and are often placed on street intersections or three-way junctions, especially in the crossing."

Ishigantō were introduced to the Ryūkyū Kingdom from China and can be found throughout Okinawa Prefecture, where they are also called Ishigantu or Ishigandō, and to some extent in Kagoshima Prefecture, where they are known as Sekikantō or Sekkantō.

On Kikai-jima (Amami Ōshima), they are called majimunparē ishi(魔除け払い石). In the Yaeyama archipelago (Okinawa Pref.) they are known as ashihanshi(足はらい).

Toka Ebisu Festival

One of the nice things about living in Japan is that there is always some festival or holiday to look forward to. Unlike America where once the holiday season ends with New Year's or, ho-hum, the feast of the Epiphany on January sixth, there is a long lull in festive events, in Japan something fun is always just around the corner. Once Christmas has passed, the trees come down and up go the kadomatsu and other New Year's decorations. After the five or six-day drinking, eating, and TV-viewing binge known as O-Shôgatsu, or the Japanese New Year, comes Tôka Ebisu, a festival honoring Ebisu, the patron deity of businesses and fisheries. At around the same time, the Coming-of-Age Day celebration celebrating the entry into adulthood of the nation's twenty-year olds, is held. There is the bean-throwing exorcism known as Setsu-bun in early February, as well as a number of local festivals held in shrines and temples in the meantime.

On Sunday, I went to Fukuoka's main Ebisu shrine which is located just outside of Higashi Park. While I sometimes miss the New Year's celebrations do to travel, I always manage to get back in time to attend the Tôka Ebisu festival.

Like most other festivals held throughout the year in Japan, you'll find the usual demisé food stalls selling o-konomiyaki (below), jumbo yakitori, and so on. What makes Tôka Ebisu different, however, is the number of stalls selling good luck items featuring the seven lucky gods (Shichi Fukujin) of which Ebisu is one, talismansand other trinkets to ward off bad luck, and so on.

The festival also attracts a much different class of people. Whereas you can see many young men and women at the harvest festival Hôjoya (also known as Hôjoe), the people attending Tôka Ebisu tend to be older and "tarnished", making it an interesting place to people watch. I never fail to find the middled aged mamas of "snacks", rough-looking men who look as if Ebisu hasn't been very generous to them, and others desperate for an auspicious start to the new business year.

This year, there seemed to be far more people at the festival than usual. Perhaps it was the weather, perhaps it was that after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami everyone is hoping for a bit of luck.

Sweet roasted chestnuts.

If you look closely at the apex of the crowd in the picture above you can see an upside down red fish, a sea bream. This is a symbol of Ebisu who is often depicted carrying one. In Japanese the sea bream is called tai which rhymes with medetai, meaning “happy”, “auspicious”, or “successful”. Real sea bream are often displayed at a celebratory gatherings, such as New Years, the end of sumô tournaments, engagement ceremonies, and so on.

Just beyond the red sea bream is a procession of the Hakata Geiki, a troupe of geisha working in Fukuoka City. I’ll write about them in a later post in the coming months. Incidentally, the photo on the cover of my second novel, A Woman’s Nails, was taken at this event several years ago.

The geisha making their way to the shrine. This procession is held every year at the height of the Tôka Ebisu festival and worth seeing. This year we just happened to be there when it was taking place.

Another feature of Tôka Ebisu is the drawing that is held at the shrine. On either side of the shinden there are booths selling tickets.

The first time I attended the festival was over ten years ago and didn’t know what to expect. So, when I pulled out one of the lots from a hexegonal box and the Shintô priest shouted, “Ôatari!” (Jackpot!), my mind filled with delicious possibilities: a new car? A trip to Hawaii? Cash? I had never ever won so much as a cakewalk or bingo game before. Needless to say, I was quite excited.

As another priest pounded out several beats on a drum and shouted “Ôatari,” the first priest pulled out a huge red fan from a pile of trinkets and talismans behind him and passed it to me. The fan had 商売繁盛 (shôbai hanjô, “prosperity in business”) written on it in large white characters. Prosperous was the last thing I felt.

That didn’t stop me, however, from going back year after year and trying my luck. In the past, the tickets were only ¥1,500. Today, they go for ¥2,000 each—so much for the deflationary pressure we are told has been pushing prices lower and lower—and where I once bought two or three of the tickets, I now only buy one.

Over the years I have “won” two of those large red shôbai hanjô fans, a massive wooden paddle as big as a cricket bat that has 一斗二升五合[1] written on it, a plate featuring Ebisu-sama, a wooden piggy bank, a calendar, and a small Ebisu doll.

A dutiful follower of this cult of Ebisu, I went on the tenth of January last year. The weather was awful—freezing cold and rainy—and I had been forced to wait under a canopy that leaked like a sieve for a good hour and a half until my wife and son showed up.

When they finally did, I was in a foul mood. My pant legs and shoes soaking wet, the cold was beginning to seep into my bones.

“Let’s just get the damn thing and head on home, okay?” I grumbled to my wife. “It’s freezing!”

We hurried into the shrine, which thanks to the lousy weather was not as crowded as it usually can be during the festival. There was only a handful of people in line for the drawing.

Well, no sooner had we handed over our ¥2000 at the reception desk than the man at the counter said, “Congratulations, you’re our twenty-five-thousandth visitor.” Or something like that. He had us fill out a form and then asked us to follow him to the place where the lots were drawn. After handing the form to the priest with the box containing the lots, I was told to pull one of the sticks out. It didn’t matter which. I did so and gave it to the priest who stood up and, turning on a microphone, said he had a big announcement to make.

“We have a major prize for our twenty-five-thousandth visitor today!” Another priest started banging away at a drum. The other priests in the shinden stopped what they were doing, stood up, and started clapping in unison. After a number of Banzais, the priest handed over a massive and cumbersome bamboo rake to me. It was adorned with ceramic depictions of the gods Ebisu and Daikoku, a red sea bream, a bale of rice, and other auspicious items.

Let me tell you, I couldn’t have been more thrilled had I won a trip to Hawaii.

I don’t know if it is thanks to Ebisu-sama, my son whose arrival in my life signaled the beginning of things finally going my way, or plain dumb luck, but last year ended up being the very best year ever in so many ways.

When you’ve already won the jackpot, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to continue dropping quarters into the slot machine, and yet that is essentially what we did by returning to the Ebisu festival this year and trying our hand at the drawing again.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” my wife said.

“I know, I know,” I replied. “But still, it would be nice to get one of those boats with the seven lucky gods in it. I’ve always wanted one for the collection.”

Sure enough, Ebisu wasn’t as generous to us this year: we got a simple little wooden abacus. I suppose the message the gods are trying to tell us is that we should be more careful about how we spend money. Duly noted, Ebisu-sama!

[1] Ask your Japanese friends to try reading 一斗二升五合and most of them will be stumped. It is a riddle of sorts employing 斗, 升, 合 all of which are traditional Japanese measures of volume.

一斗 (itto, about 18 liters) is equal to ten 升 (shô, about 1.8 liters). 一斗, then, can be said to equal 五升の倍 (go shô no bai), which means “five shô doubled”. 五升の倍 (go shô no bai) is synonymous with 御商売 (go shôbai) which means “one’s business or trade”. Got that?

二升 (nishô). 升 can also be read masu. 二升 here is read “masu masu” which sounds like 益々 (masu masu), meaning “more and more”, “steadily”, and so on.

五合 (go gô, 5 x 0.18 liters, or 0.9 liters) is one half of a shô or 半升 (hanjô) which sounds the same as 繁盛 (hanjô, prosperity). So, putting it all together 一斗二升五合 can be read “Go-shôbai masu masu hanjô!” (御商売益々繁盛), meaning something to the effect that your business or trade will enjoy increasing prosperity.

Dazaifu Tenmangu (太宰府天満宮) is Fukuoka's most famous shrine.

Sansha Mairi

If you live in only one region of Japan for an extended time as I have, it’s easy to make the mistake of assuming that what is true in the town you reside in is also true throughout the rest of the country.

I first recognized this many, many years ago when I kept getting tripped up by the local dialect, known as Hakata-ben (博多弁). I’ve written about this elsewhere, but what I’m getting at here here is not my failure to understand what someone is saying because he is speaking the local dialect, but rather people not understand what I am saying because I have unwittingly used the dialect thinking that what I was speaking standard Japanese.

Take the Japanese word koi (濃い), which can mean deep, heavy, dark or thick—such as in koi aka (濃い赤), “deep red”; koi sūpu (濃いスープ) “thick soup”; ~ wa ajitsuke ga koi (〜は味付けが濃い) “. . . is strongly seasoned”; or even chi-wa mizu-yorimo koi (血は水よりも濃い) “Blood is thicker than water.” For the first ten years of my life here in Fukuoka, I thought koi was pronounced koyui. (Try looking it up in a Japanese-English dictionary.) If you go to Tõkyõ and ask a bartender to make you a stiff drink, saying “make it koyui”, he’ll probably give you a funny look.[1]

Traditional foods, too, can vary from region to region in Japan, so much so that a simple dish like o-zōni—a soup eaten during New Year’s—can contain radically different ingredients and yet still be called o-zōni.

Customs, as I have mentioned before, also differ from prefecture to prefecture. The Bon Festival of the Dead, for example, can, depending on the region, be held as early as July 15th (in Shizuoka, for example) or in other parts on August 15th. Some regions, such as Okinawa, observe what is known as Kyū Bon (旧盆) which falls on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month. In 2019, Kyū Bon and “regular Bon” will take place at the same time, namely from the 13th to the 15th of August. Living all this time in Kyūshū, I used to assume that all Japanese celebrated the Bon in the middle of August and would pester everyone with the question: “Why isn’t this a national holiday like New Year’s?”

Stop pushing’!

Now only a few years ago, it finally dawned on me that something I had taken for two decades to be a widely-observed custom was actually a very local one: sansha mairi (三社参り).

In Japan, many people (and I would venture most) visit a Shintō shrine during the first few days of the new year, a custom known as hatsumōdé (初詣), to pray or make wishes. At the shrines, they buy good luck charms called o-mamori (お守り), drink a special kind of saké, and buy written oracles known as o-mikuji (おみくじ). It’s primarily in Fukuoka, though, that people visit (o-mairi, お参り) three shrines (三社) rather than one.

Live and learn.

God? You up there? Do you hear me, God?

So When is O-Shogatsu Over Anyways?

This is a piece I wrote for GaijinPot last year.

My wife took down the shime kazari the other day.

Shime kazari are the decorations you find hanging on front doors and gates at o-Shōgatsu (お正月, or the Japanese New Year). Traditionally made with twisted rice straw, they are often festooned with a daidai (bitter orange), fern fronds and gohei or shide (zigzag strips of white paper), the ornaments serve to welcome Toshigami-sama, the Shintō deity who brings a bountiful harvest and blessings for the new year.

Modern designs, like ours (above and below), take great liberties with more traditional decorations, adding generous loops of red-and-white cords of twisted paper, known as mizuhiki, pine branches, colorful Japanese washi paper, auspicious doodads and occasionally fresh flowers.

I asked my wife what she was doing.

“Shōgatsu is over… ”

“Says who?”

“My parents already took down their shime kazari.”

“So? I paid ¥4,000 for that. Put it back. Please!”

“But… ”

There’s quite a bit of debate about when you should take your New Year’s decorations down. Regional variations have something to do with it — why, even the design of the shime kazari themselves can vary greatly from region to region — but so do different interpretations of when o-Shōgatsu is officially concluded.

I guess you could say a similar discussion exists in the West concerning when Christmas trees should be tossed out. Is it the Feast of the Epiphany, which falls on Jan. 6 (hence the 12 Days of Christmas)? Or should the tree and other holiday decorations remain until Candlemas, which falls on Feb. 2, i.e. 40 days after the nativity of Jesus? Thanks to Christmas tree recycling drives hosted by the Boy Scouts in early January, in America at least, trees are now being ground up into mulch before they can become a fire hazard.

As for the last day of o-Shōgatsu, many assert that it is Jan. 7. This day is widely considered to be the final day of matsunouchi, the week-long period starting with New Year’s Day during which the kadomatsu (New Year’s “gate” pine) and other decorations are displayed. New Year’s greeting cards, known as nengajō, should be received within the first week of the year. The seventh is also the day Japanese eat nanakusa gayu, a dishearteningly bland rice porridge dish made with seven different herbs. It was for these reasons, I suspect, that my wife’s mother and many others had already taken their own decorations down.

But, I still wasn’t sold on the idea.

During a quick walk around my neighborhood, I noticed several shops were still displaying their shime kazari. Perhaps because it was Seijin-no-hi, or Coming-of-Age Day, a national holiday that serves as a psychological bookend to New Year’s.

Whatever the shops’ motivations, some believe that it’s quite alright to keep the decorations up until Jan. 15, a date known as Ko-Shōgatsu (小正月, Little New Year), as was the custom up until the Edo Period (1603-1868). The first week of the new year was called Ō-Shōgatsu (大正月, lit. “Big New Year,” in this instance) while the rest of the month was considered just regular “Shōgatsu.”

Rice porridge with seven herbs and salt.

Ko-Shōgatsu is known by other names, too, such as Niban Shōgatsu (Second New Year’s), Onna Shōgatsu (女正月, Woman’s New Year) and so on. Before Japan adopted the Gregorian solar calendar, the 15th was the day on which the full moon appeared. As far back as the Heian period (794-1185), it was customary to eat rice porridge made with sweet, red azuki beans. A similar dish called o-shiruko (sweet red-bean soup), made with azuki beans and half-melted globs of mochi (sticky rice cake) is traditionally eaten around the 11th, the day kagami (mirror-shaped) mochi decorations are broken. Today, at shrines throughout Japan, you can find hi-matsuri (火祭り, fire festivals), known as sagicho or dondoyaki (burning of New Year’s gate and other decorations), held on the 15th when kadomatsu, shime kazari and the previous year’s talismans are set alight in a bonfire.

Despite that, others argue that it’s acceptable for New Year’s decorations to remain until Hatsuka (20th day of the month) Shōgatsu, which falls, not surprisingly, on the 20th of January. In the Kansai area, the head and bones of the buri (Japanese amberjack) are cooked with sake kasu (lees), vegetables and soy beans. Because of this, the day is also called Honé (bone) Shōgatsu.

My wife, following her mother’s example, had been deferring to tradition. I countered with the argument that if we were really going to stick to good ol’ “tradition,” we would have to keep the shime kazari up until March 2, which — in accordance with the Chinese lunar calendar — is actually Jan. 15.

“Let’s keep it up until Hatsuka Shōgatsu, then,” my wife suggested.

“The 15th will be fine,” I said. “We don’t want to get carried away.”

Shimenawa

Shiménawa (七五三縄, 注連縄 or 標縄, literally "enclosing rope") are another common decoration of the Japanese New Year. Rice straw is braided together to form a rope, that is then adorned with pine, fern fronds, more straw and mandarine oranges. They can represent a variety of auspicious items, such as the rising sun over Mt. Fuji or a crane. The shiménawa pictured above is the one that hung on my front door a few years ago.

Used mostly for ritual purification in the Shintô religion, shimenawa can vary in diameter from a few centimetres to several metres, and are often seen festooned with shidé paper. The space bound by shimenawa often indicates a sacred or pure space, such as that of a Shintō shrine.

Shiménawa are believed to act as a ward against evil spirits and are also set up at a ground-breaking ceremonies before construction begins on a new building. They are often found at Shintō shrines, torii gates, and other sacred landmarks.

They are also tied around objects capable of attracting spirits or inhabited by spirits, called yorishiro. These include trees, in which case the inhabiting spirits are called kodama, and cutting down these trees is thought to bring misfortune. In cases of stones, the stones are known as iwakura.

Most of the following photos were taken of shiménawa hanging at the entrance of restaurants and boutiques in my neighborhood.

This is the kind of shimékazari typically found in Fukuoka.