I’ve been living in Japan long enough that I know almost all of these political parties.

I can even remember some of the faces behind them, one of whom was Ozawa Ichirō (小沢一郎). Ozawa left the Liberal Democratic Party in the early 93 to form the Japan Renewal Party (新生党, Shinshintō). It was dissolved in December of the following year and merged into the New Frontier Party (新進党, also pronounced Shinshintō, but with a different Chinese character in the middle). The second Shinshintō was created from the merger of like-minded, or rather like-ambitious, politicians from five different parties only to splinter three years later into the New Fraternity Party (新党友愛, Shintōyūai) and Liberal Party (自由党, Jiyūtō). Neither lasted very long and both would, I believe, merge into the Democratic Party of Japan (民主党, Minshutō), which came to power in 1998. Minshutō split into two other, now forgotten parties, plus the Democratic Party (民進党, Minshintō), which finally fizzled in 2018. Many of those former Democratic Party pols jumped ship, joining one of two emerging parties—the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (立憲民主党, Rikken Minshutō), which is now the largest opposition party, and the Democratic Party for the People (国民民主党, Kokumin Minshutō), which is currently in talks with the LDP to form a coalition government.

Phew.

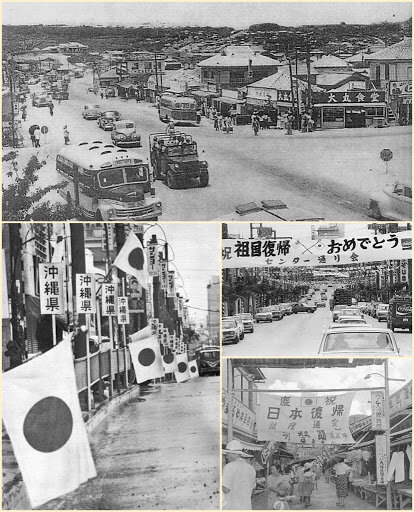

Okinawa Henkan

The US Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands ended on 14 May 1972 when the prefecture was "returned" to Japan the following day. Ryukyuan postage stamps and passports had been in use, and the dollar was the currency until then. Cars continued to drive on the right till 1978.

The return of Okinawa was never a foregone conclusion because the US used the islands as a bargaining chip--first with the Chinese in November of 1943 to keep Chiang Kai-shek from concluding a peace deal with Japan and keep them in the war, then with the Japanese to prevent her from concluding a peace treaty with the USSR. The US warned Japan that if they were to do so, America might keep the Ryukyus under US control forever.

Realpolitik is hard ball.

Before switching to left-hand drive (L) and after the switch in 1978 (R).

Blessed

Back when I did a lot of translation work, there was a phrase that I was forced time and again to render into English: utsukushii shizen ni megumareta (美しい自然に恵まれた, lit. “blessed with beautiful nature”). I would translate it in a variety of ways, such as “The prefecture is blessed with bountiful nature”, “The city is surrounded by lots of natural beauty”, or “The town is surrounded by beautiful nature.” Or even, “It is located in an idyllic natural setting.” I found that if I took too much poetic license in my translations, they invariably came back to me with “You left out ‘beautiful’” or “You failed to mention ‘nature’ in your translation”. Whatever.

The thing that killed me when I was doing these translations is that I would look out my window at the jumble of telephone wires and cables, the lack of trees, the concrete poured over anything and everything that hadn’t been moving at the time, the gray balconies and staircases stretching as far as the eye could see and shout, “Where the hell is the ‘beautiful nature’? Tell me!! Where is it?!?!”

Having grown up in the west coast of the United States, I know what unspoilt nature is supposed to look like. In my twenty years in Japan, however, I have yet to find a place that has not been touched by the destructive hand of man despite having seen quite a bit of the country. Mountains that have stood since time immemorial are now “reinforced” with an ugly layer of concrete; rivers and creeks are little more than concrete sluices; and Japan’s once beautiful coastline is an unsightly jumble of tetrapods—concrete blocks resembling jacks—that are supposed to serve as breakwaters but do very little in reality.

The uglification of Japan has been well documented in Alex Kerr’s excellent and highly recommended books Lost Japan and Dogs and Demons.

"Today's earthworks use concrete in myriad inventive forms: slabs, steps, bars, bricks, tubes, spikes, blocks, square and cross-shaped buttresses, protruding nipples, lattices, hexagons, serpentine walls topped by iron fences, and wire nets," he writes in Dogs and Demons.

"Tetrapod may be an unfamiliar word to readers who have not visited Japan and seen them lined up by the hundreds along bays and beaches. They look like oversized jacks with four concrete legs, some weighing as much as 50 tons. Tetrapods, which are supposed to retard beach erosion, are big business. So profitable are they to bureaucrats that three different ministries — of Transport, of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and of Construction — annually spend 500 billion yen each, sprinkling tetrapods along the coast, like three giants throwing jacks, with the shore as their playing board.

These projects are mostly unnecessary or worse than unnecessary. It turns out that wave action on tetrapods wears the sand away faster and causes greater erosion than would be the case if the beaches had been left alone."†

One of Japan’s recurring problems is that once something has been set into motion it is often difficult to change course. As a result, by the early 90s more than half of Japan’s coastline had already been blighted by these ugly tetrapods. I dread to know what the figure is today.

One of first of my imaginary political party’s[1] campaign promises is to form a Ministry of De-construction that would remove unnecessary dams, tetrapods, concrete reinforcements, and so on. The idea is to put the ever so important general construction industry to work by undoing all of their mistakes. Second, where the dams, reinforcements and tetrapods were truly necessary, they would be concealed in such a way to look as natural as possible. Third, the electric cables would be buried. Fourth, there were would be stronger zoning and city planning to reign in urban and suburban sprawl. (Too late?) Create compact, highly dense cities that were separated from each other by areas of farming, natural reserves, and parks. (One thing I can’t get is how in a country with as large a population as Japan’s and land as limited put vertical limits on construction—Fukuoka City once had a limit of 15 stories). Fifth, reintroduce diversity to the nation’s forests. No more rows upon rows of cedar that not only look ugly, but give everyone hay fever in the spring.

Unfortunately, none of these things are bound to happen anytime soon. The Japanese are so accustomed to being told in speeches and pamphlets that their town or city is blessed with beautiful nature that they have come to believe it despite what they surely must see with their own eyes.

Familiarity sometimes breeds content.

[1] I call my party Nattoku Tô (なっとく党, The Party of Consent/Understanding/Reasonableness). It is a play on the sound of the local Hakata dialect and with the right intonation can me “You got that?” “Can you assent to that?”

†Kerr, Alex, Dogs and Demons: The Fall of Modern Japan, London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2001, p.289.

Iturup

This is Iturup (also known as Etorofu-tō (択捉島) in Japanese). I used to joke to my Japanese friends, “Why do you want these islands back so badly? Do you want to live there? No? So, what’s the big deal?”

“The natural resources,” they say.

Out of curiosity, I googled Iturup and found these absolutely stunning.

Now imagine if this and other disputed islands in the Kuril chain had remained in Japanese control after WWII. The beach today would surely be covered with tetrapod blocks, the white cliffs enveloped with concrete.

HRP's campaign poster for the 2014 general election features party president, Shaku Ryōko. The former party head used to be Ōkawa Kyōko, the wife of Happy Science founder Ōkawa Ryūhō. Seems they failed to realize their happiness together.

Dubious Science

The first time I heard of Happy Science was during the 2009 Lower House election that would had the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) a well-deserved drubbing.

One day during the 12-day campaign period before the election,[1] a noisy political sound truck sped past me with the usual contingent of white gloved hands waving out of the windows and the improbable name Kōfuku Jitsugen Tō (幸福実現党, The Happiness Realization Party, HRP) plastered on the side of it.

“You gotta be kidding,” I said to myself as I waved back listlessly to the enthusiastic lackeys in the van.

In 2009, there was no shortage of minor political parties with silly names, including “The Essentials”, “The Freeway Club”, “Japan Smile Party” and “The Forest and Ocean Party”, none of which would gain any seats in the election. The Happies, however, would press on election after election.

Curiosity getting the better of me, I did a bit of research into the party when I got home that day and I learned that HRP was the political wing of Kōfuku no Kagaku (幸福の科学, Happy Science), a cult founded in 1986 by Ryūhō Ōkawa.

According to an article in The Japan Times, “the Happies have an eye-catching manifesto: multiply Japan’s population by 2 1/2 to 300 million and make it the world’s No. 1 economic power, and rapidly rearm for conflict with North Korea and China. If elected, the party’s lawmakers will invite millions of foreigners to work here, inject religion into all areas of life, and fight to overcome Japan’s ‘colonial’ mentality, which has ‘fettered’ the nation’s true claim to global leadership.”

I don’t know about you, but it sounded to me as if the person who wrote the manifesto had been smoking meth.

Pipe dream or not, Kōfuku Jitsugen Tō fielded 345 candidates, or nearly one in each electoral district—more than the either the Democratic Party of Japan, which would go on to win the election, or the ruling Liberal Democratic Party—in the 2009 election, yet failed to win any seats in the National Diet. Further bids in 2012 and 2014 with a similar number of candidates also yielded zero seats. At a cost of 3 million yen per individual electoral district and 6 million yen per proportional representation block, The Happies have squandered almost six billion yen (over $50 million) over the past three campaigns.

Or have they?

If the real aim of these hopeless election campaigns has been brand recognition rather than electoral victory, then The Happies must be very happy indeed. Six years ago, I had never heard of either the cult or its leader, but now I have. I’m sure it is no different with your average Tarō in Japan.

Still, fifty-plus million dollars ain’t chump change. By comparison, Mitt Romney spent $42 million of his own money in his failed attempt to win the Republican nomination for presidential candidate in 2007-08, the second most spent by a candidate self-financing his run. All of this got me thinking how The Happies were able to finance not only their election campaigns, but also their construction boom which has seen several gaudy new palaces dedicated to the ego of Ōkawa erected throughout Japan over the past several years.

It’s hardly news that religions, old and new, are able to generate fabulous amounts of tax-free income, but to make money, they’ve got to have adherents to their faith.

According to Happy Science’s, the cult claims to have twelve million followers in ninety countries. I found this number to be highly dubious as it is the exact same figure claimed by another cult, Sōka Gakkai. Although considered a “new religion” in Japan, S.G. International has been around since 1930 and has its origins in Nichiren Buddhism, which itself dates back to the 13th century. Although, I do not know anyone who is a follower of Ryūhō Ōkawa, I have come across quite a few members of Sōka Gakkai over the years. The entertainment world in Japan is famously peopled with followers of the religion.

By comparison, the Mormons[2] have over 15 million followers and the Jehovah’s Witnesses have 8.2 million, thanks to both religions’ aggressive missionary work throughout the world and unfortunately at my doorstep.

The more I ruminated on it, the more Happy Science’s claim of twelve million believers just didn’t add up.

Then it hit me. I knew how to get a fairly accurate estimate of Happy Science’s followers in Japan: the results of the 2009 election.

In the proportional representation blocks, The Happiness Realization Party and Kōmeitō, the party closely tied to Sōka Gakkai, got the following number of votes:

Hokkaidō Block

20,276 votes for HRP vs. 354,886 for Kōmeitō

Tōhoku Block

36,295 vs. 516,688

Northern Kantō Block

46,867 vs. 855,134

Southern Kantō Block

44,162 vs. 862,427

Tōkyō Block

35,667 vs. 717,199

Hokuriku Block

32,312 vs. 333,084

Tōkai Block

57,222 vs. 891,158

Kinki Block

80,529 vs 1,449,170

Chūgoku Block

32,319 vs. 555,552

Shikoku Block

19,507 vs. 293,204

Kyūshū Block

54,231 vs. 1,225,505

The Happiness Realization Party garnered about 459,000 proportional representational votes, less than 6% of the 8,054,000 votes for the Kōmeitō, which suggests that The Happies actually have around 720,000 followers. After watching this video of Ryūhō Ōkawa’s great psychic power, it makes me wonder how he managed to even get that many.

Obviously, I'm in the wrong business.