It happened again, that useless intuition of mine.

For no particular reason, I started thinking about my friend Mika. I hadn’t seen in well over a year and wondered aloud one evening whether she was still running her children’s clothing boutique. She had given birth to a second child—a boy—about a year earlier, so I had my doubts. I decided then that I would try and take my son there after visiting Ajibi [1] and told my wife so. Well, as luck would have it, Mika called me up the very next day to say that she was in the neighborhood and wanted to drop by.

“By all means, do come over!”

Mika and I used to be drinking buddies, and for a few years running we were getting together about once or twice a week. She was a core member of a nebulous group of boozers and diners, mostly Japanese women, with whom I would go out for dinner or drinks or to parties. As is often the case with groups like that, unfortunately, it seldom lasts. Transfers, marriages, pregnancies, all have a way of chipping away at the camaraderie. And in the case of that particular group, two women were transferred away, and Mika got knocked-up and eventually married. It was just as well: by the time I turned forty I was spending less and less time in clubs and bars and more time sitting in cafés writing.

“I’ve gotten divorced,” Mika told me as soon as she entered my front door. She had both children with her.

“Um, congratulations?”

I wasn’t surprised. The only reason my friend had gotten married in the first place was the first pregnancy; the only reason she hadn’t already divorced was the second.

“We’re still together. Living together, that is.”

“Oh?”

“Until I can save up enough money for a deposit on an apartment.”[2]

“I see.”

Mika put her ten-month-old son down on the floor. The kid looked like he would one day have a promising career in the sport of sumô wrestling. “I still control all of his money,” she said.

“How about your shop?”

“I closed it after I got pregnant with him.” Her son sat up and smiled at me, flashing me four new teeth. “He was a ‘mistake’.”

“Cute ‘mistake’,” I said, picking him up. “Heavy, too!”

“Yeah.”

Mika went into my kitchen and started to fix her son a large bottle of formula. As she was heating up some water, she told me that her son had been easy to bring up, much easier than her daughter.

“It’s often the opposite,” I said. My poor wife has had to contend with raising two very active boys.

We wouldn’t mind also having a daughter, but the odds of my loins producing another feral laddie are, well . . . why play with fire, right?

. . .

About two months ago in one of my writing classes, a student wrote in her diary that she had recently “found” her father on Facebook. When I asked her about it, she told me that her parents had divorced when she was just a toddler. She had never met her father since then. Thanks to Facebook, though, she and her father not only “friended” each other, but were going to be reunited in a few days. I asked her if she had told her mother and she answered, no, it was a secret. Her mother had apparently remarried while she was still very young.

It’s not unusual in Japan for couples who divorce to completely sever ties with each other after breaking up. I even know of one couple who had two children—a boy and a girl. When they divorced, they decided that it would be “best” if their daughter stayed with her mother, and the son go on to live with his father.

“And the two have never met since they were young children?” I asked.

“No, never. Not even once.”

Never mind the possibilities for an intriguing Oedipal tale of siblings reuniting by chance and having an incestuous relationship, this struck me as just plain wrong on so many levels.

My own children keep me up most nights, crying and screaming and kicking and even pinching me. The apartment, which I prefer to keep neat and tidy, is usually a mess now, toys and picture books and used diapers are all over the place. Laundry and dishes pile up. More and more money is being spent on the kids; my allowance is getting smaller and smaller. And in spite of all the giving and compromising that is part and parcel of being a parent, I could never imagine those two boys not being in my life. I adore them too much. So, it seems to me like a lot of unnecessary grief to cut a parent or child out of your life like that.

Expert in Japanese psychology and society will tell you that the Japanese tend to avoid “complicated relationships”. This is one reason why it is so uncommon for the Japanese, even college students, to have roommates. Try as I might to sell them on the idea of living in a much bigger apartment for far less rent if only they shared the place with a friend, but they invariably grimace or suck air through their teeth and make vague allusions to a need for privacy. [3] It is also the reason why after divorce many Japanese will break off all ties with their former spouse, even if that means no longer seeing a child.

I asked the twelve students in that writing class of mine how many of their parents were divorced and was surprised to learn that almost half of them were. All of them—it’s a woman’s college—lived with their mothers, and very few of them had any contact with their fathers. Only one actively maintained a relationship with her father. The others hated their old man, no doubt influenced by the opinions of their mothers. As an “old man” myself I couldn’t help but feel for these estranged fathers.[4]

. . .

After an hour or so, Mika’s former husband and current roommate called. He was in the neighborhood and ready to take their kids home. All of us—Mika, her kids, my wife, our boys, and I—went downstairs and waited for him to show up. When he did, he stepped out of the car, walked towards me and shook my hand. It was our first time to meet (and, probably our last as well).

I was struck by how good-looking the guy was (Mika's not bad-looking herself) and I said so after he had left with the kids.

“His looks are the only thing that’s good about him,” Mika said.

Mika then said she had to be going herself, adding as she turned to leave that she would contact me once she had found a new place to live.

(This is normally where Americans would hug each other tightly, but we just waved and said good-bye.)

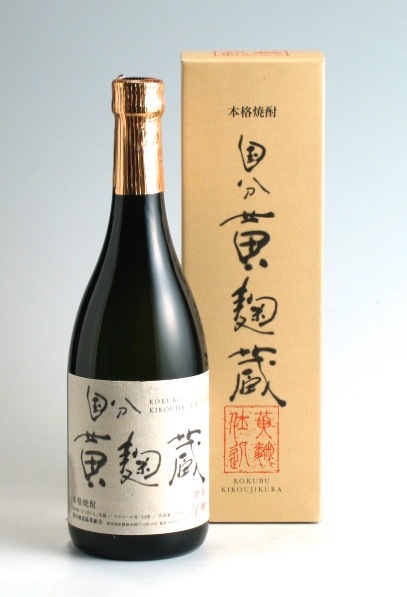

Mika had brought a bottle of shôchû with her when she came, asking the silly question: “You still drink, don’t you?”

“Does the pope shit in the woods?”

. . .

After Mika left, I went back upstairs and opened the bottle. It was Iichiko’s Hita Zenkōji. I’m not a big fan of Iichiko, as I have mentioned earlier, but with my first sip of Hita Zenkōji the scales fell from my eyes. Just as Ron Zacapa Centenario had reacquainted me with rum, an alcohol I once avoided at all cost, Hita Zenkōji was now introducing me to the potential of mugi (barley) jōchū.

After several glasses of Hita Zenkôji, a warm sentimentality came over me.

For your kids’ sake, Mika, I do hope you can keep your ex-husband in their lives even after you move out. And I don’t mean for some banal crap like “sons need their fathers”, but rather, so that your children can grow up learning that even when people disagree or fall out of love, they can still show civility and respect to each other, that even “complicated relationships” can have their merits.