No sooner do I grumble about not getting summer gifts anymore than a student comes through and presents me not only with a gourmet selection of mentaiko-flavored[1] cheeses, but with a fine bottle of imo shōchū.

One of the most difficult aspects in writing about shōchū is that differences in taste can be very subtle. I suppose that is to be expected, considering that the ingredients vary little from imo shôchû to imo shôchû: they are, namely, water, sweet potato, and kōji (malted rice). Granted, there are all kinds of sweet potatoes, as a visit to any shōchū shuzō (distiller) will quickly impress upon you. There are also different kinds of kōji which greatly influence the taste of a shōchū.

The three types of kōji used in the production of shōchū are black kōji, white kōji, and yellow kōji, so named for the color of the bacterial spores. The type of kōji-kin (aspergillus) bacteria used affect not only the distillation process but also the flavor of the end product.

Yeast and kōji-kin are indispensible for the distillation of shōchū. Starch from the potatoes are broken down into glucides (sugars), a process known as saccharification, by the kōji-kin and then yeast metabolizes the sugar, producing alcohol (ethanol).

Kuro Kōji (黒麹)

Kuro Kōji, or black kōji was originally introduced to Kyūshū from the Ryūkyū Kingdom (present-day Okinawa). It is very good at producing citric acid which protects against both the propagation of bacteria and the spoiling of unrefined sake. It is perfect for the subtropical climate of Okinawa. For that reason, it is used in the production ofawamori. Generally speaking, imo shôchû made with kuro kōji pack a punch. They are fuller bodied and have a conspicuous flavor.

Shiro Kōji (白麹)

Shiro kōji, or white kōji, is a mutation of the kuro kōji bacterium that is cultured and used mainly in Kyûshû. Because it has greater enzymatic power than kuro kōji, and does not release spores like kuro kōji which can soil both the clothes of the workers and the distillery, the use of shiro kōji has spread widely and quickly. It produces a mellow-tasting, mild shōchū bringing out the flavor of sweet potatoes.

Kikōji (黄麹)

Kikōji, or yellow kōji, is usually employed in the production of seishu (清酒, refined saké) and saké. Because it lacks citric acid which protects against spoilage, it was not considered suitable for shôchû. In recent years, however, the use of yellow kōji has grown in popularity. With its fruity nose, imo shôchû made with yellow kōji, such as Tomi no Hōzan are changing the way people think about imo jōchū.

Kampai!

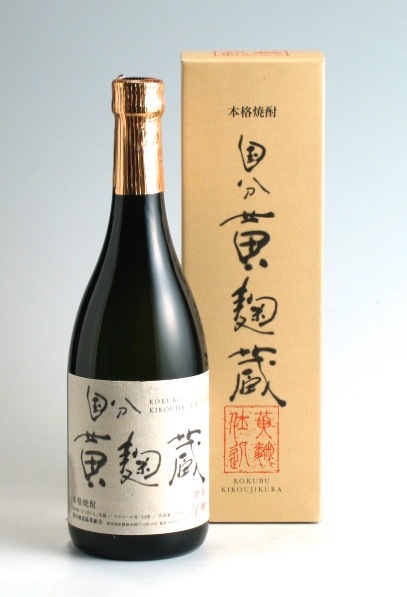

国分 黄麹蔵 (Kokubu Kikōjikura)

25% Alc/Vol

Made from potato and yellow kôji.

Nose: ★★★

The fragrance belies somewhat how flavorful this shōchū is.

Palate: ★★★★

Strong alcohol flavor, with unique after taste that fills the nose to the rafters when swallowed.

Overall: ★★★☆

[1] Mentaiko (明太子) is a local delicacy in Fukuoka City, made of cod roe marinated in red chili pepper powder and other seasonings. Well-known throughout Japan today as a souvenir from Hakata, mentaiko was first introduced to Japan after the Pacific War by Toshio Kawahara, the founder of Fukuya. Born in Busan, Korea, Kawahara returned to Fukuoka after the war where he adapted the flavor of Korean myeongran jeot such that it better suited Japanese tastes. He called his product Aji no Mentaiko (味の明太子) and started selling to bars and izakaya(pubs) from a shop he had in the entertainment district of Nakasu. Because Kawahara failed to patent the recipe, there are now hundreds of companies producing mentaiko today, including Fukutarô, Chikae, Kubota, and so on. That said, I am not crazy about the stuff.

More stories like this can be found in Kampai! Available from Amazon.